With the aim of enabling our readers to keep up with the Supreme Court of India’s day-to-day hearings for the significant case concerning the abrogation of Article 370, LAOT, in collaboration with the Centre for Constitutional Law, NALSAR is bringing you a concise daily summary of what was argued in the Court. This is the summary of Day-1 proceedings.

Note: CJI Chandrachud clarified that the cause title of the case will read In Re: Article 370 petitions. Since many cases are tied together, no petitioner’s name will be reflected in the title itself.

Today, a five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court commenced hearing the petitions challenging the abrogation of Article 370. The Supreme Court is supposed to hear the matter for many days to come. While the Court will continue hearing petitions challenging the abrogation, we will also summarise the line of arguments here. As indicated in our introductory post, the case is significant in the sense that it touches upon the questions of democracy, the Treaty of Amritsar, the Dogra rule, the Instrument of Accession, the nature of Jammu and Kashmir’s (“J&K”) accession with India, the interpretation of Article 356, the powers of the Governor, the residuary power, constituent power, among many other questions of great importance.

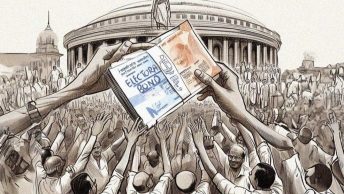

When the Bench commenced this morning, Senior Adv. Kapil Sibal began the arguments for the petitioners. He questioned the procedure adopted by the Parliament for abrogating Article 370. He also asked whether the procedure was consistent with democratic principles. Mr. Sibal highlighted the delay in taking up the case by the Supreme Court and the lack of representative government in J&K for all these years. Mr. Sibal explained the historical importance of this relationship between the Union of India and the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir.

He questioned the method adopted by the Governor as it took him one day to decide that government formation was impossible in J&K. Mr. Sibal said that this petition presents unique questions to the Court, which the Court has never decided in its history. Mr. Sibal maintained his liberal position on the larger political issue claiming that the integration of J&K into the Union of India was unquestionable. The critical documents for the Court to examine in the case are: the Constitution of India; Constitution of India as applicable to J&K; Constitution of J&K; and Article 370.

In the paragraphs below are some essential legal-constitutional questions from today’s arguments in the Supreme Court:

Constituent Assembly as a “political exercise.”

Mr. Sibal argued that a constituent assembly stands for enacting a constitution for the future of the territories. It’s not a legal exercise but a political exercise that takes into account the aspirations of the people. This political document gives the people the right to frame the kind of state they wish to frame for themselves and thus draft a constitution. It is their separate aspirations that are taken into account. It is a document to meet their future aspirations. Because of these reasons, a parliament cannot convert itself into a constituent assembly. The Parliament cannot pass a resolution calling itself a constituent assembly. The Parliament does not get the right to declare legislature as the Constituent Assembly, certainly not under Article 356 of the Constitution of India. Mr. Sibal said that this is one of the core issues that need to be decided by the Supreme Court.

In furtherance of his stance, Mr. Sibal referred to the clause that states that the “recommendation of the Constituent Assembly will be a condition precedent” for any decision on abrogation. It is only because this ‘ultimate authority’ lay with the Assembly, which had a limited tenure that 370 was called ‘temporary.’ Mr. Sibal contended this logic by stating that the Constitution-makers had foreseen the formation of a separate constituent assembly and had envisioned this assembly as holding power to make any recommendations on the future of Article 370. Thus, through this insertion, the Constitution makers had aspired for collaboration and not the action of the Indian Parliament acting unilaterally.

This is what marks this particular arrangement different from an act of the Crown or the annexation of Junagadh or Hyderabad. This can be understood from the fact that the Constituent Assembly was mentioned in Article 370 when it had not even come into existence, even though the government of J&K could have been mentioned instead. Assigning significance to the recommendation of an Assembly with a limited tenure was thus granting permanence to the decision made during its tenure. If such permanence would not be envisioned, the authority to make recommendations could just as well have been exercised by the government of J&K.

The Chief Justice of India (“CJI”) then elaborated on the three expressions used in Part XXI of the Constitution: of these, “transitional” was not used in any headnote or marginal note, while “temporary” and “special” were used in marginal notes. Would the Article specifically using the term 370 then imply that clause (3) is no longer in effect once the tenure of the Assembly is over? The CJI further enquired why the word ‘temporary’ was used in Part XXI and if the term’s presence does not mean that Sibal’s argument is converting a ‘temporary’ provision into a permanent one despite there being no intention for the same.

Article 370 – a temporary provision?

Mr. Sibal refuted the idea that Article 370 is a temporary provision by referring to the understanding between the Government of India and the State of Jammu and Kashmir that the Constituent Assembly will determine whether 370 should be abrogated or not. It is only in the context of this understanding that 370 was called a ‘temporary provision.’ To this, the CJI raised a question about what happens to the proviso once the tenure of the Constituent Assembly is over since the proviso to clause (3) refers to the safeguard being the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly. Mr. Sibal then elaborated that this is precisely the point- that after the tenure of the Constituent Assembly comes to an end in 1957, there is no way for the Assembly to offer any recommendation on the abrogation. In the absence of such a recommendation, the President cannot issue any notification to this end.

The CJI summarized the understanding contained in Part XXI, containing three expressions- temporary, transitional, and special. He queried if we can then say that power under clause (3) goes once Constituent Assembly comes to an end. “Can this be converted into a permanent provision even though it was not intended to be?” CJI asks why there was the need to put Article 370 in Part XXI of the Constitution, which details temporary provisions.

Sr. Adv. Sibal answered his queries, stating that it is separate because two sovereigns have come together to make a compact with each other. It is temporary till such time as the Constituent Assembly desires this way or that way, argues Mr. Sibal. In repsonse, the CJI questioned the need to have the Constituent Assembly then and said that it came out of an understanding and asks if the Assembly had not chosen to join India, what would have been the consequences then. Mr. Sibal then read from the Constituent Assembly Debates of India.

Article 370 in the Constituent Assembly of India

Article 370 was originally introduced as Article 306-A by Shri N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar, who had been a former Diwan to Maharajah Hari Singh of the princely state of J&Kr. He was also responsible for the drafting of the provision. Mr. Ayyanger, while introducing the provision, said that the State had acceded to the Union, but the conditions were not normal in the State. It limited the law-making powers of the Parliament to make laws for the State to:

“…(i) those matters in the Union List and the Concurrent List which, in consultation withthe Government of the State, are declared by the President to correspond to matters specified in the Instrument of Accession governing the accession of the State to the Dominion of India as the matters with respect to which the Dominion Legislature may make laws for the State; and (ii) such other matters in the said List as, with the concurrence of the Government of the State, the President may by order specify;…”

So, what Article 370 essentially did was that it exempted the State from the provisions of the Constitution and restricted the Parliament’s legislative power to the subjects of defence, communications, and foreign affairs. For other Union powers to be extended to J&K, prior concurrence of the State Government was needed.

When asked by Maulana Hasrat Mohini why this discrimination was taking place as regards J&K, Mr. Ayyangar said that the discrimination was due to the special conditions of Kashmir, (conditions which still persist today). He said there was a war going on within the limits of J&K. He also claimed that part of the state was with the rebels and enemies. He also mentioned the fact that the issue was pending before the United Nations and was not finally settled. He reminded the Assembly of its promise to the people of Kashmir in respect of the fact that they would be given an opportunity to decide their future. The Union of India had also committed itself to an impartial plebiscite and, if the people willed, a constituent assembly to frame a constitution and define the union’s jurisdiction over the state. In the words of Mr. Gopalaswami Ayyangar, Article 306-A (which later became Article 370) was an attempt to establish an interim system until the Constituent Assembly was constituted.

We will continue this coverage in the next post summarising Day 2 of the hearings.

Aurif Muzafar is a doctoral fellow at NALSAR. He is also a Research Associate for the MK Nambyar SAARC Law Center, NALSAR.

[Ed Note: This piece is part of our series covering the hearing on the abrogation of Article 370. This post has been edited by Archita Satish and posted by Avani Vijay from our Student Editorial Team]