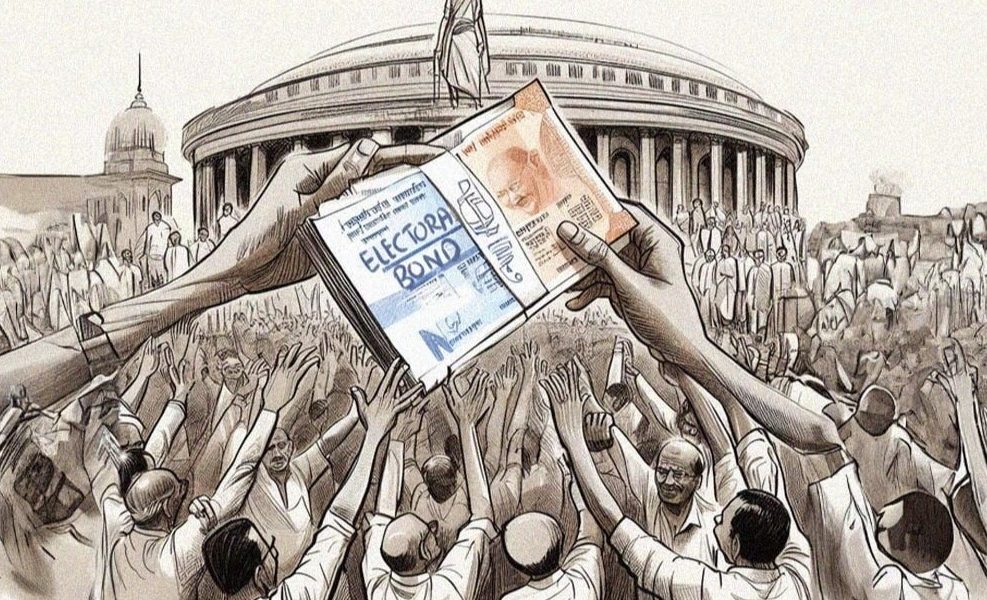

The Supreme Court’s judgment in Association for Democratic Reforms and Anr. v. Union of India and Ors. (“Electoral Bonds Judgment”) has been widely hailed as a democracy-affirming judgment, for good reason. In this post, the authors dwell into some of the nuances of the judgment, with a view to furthering the debate on its implications.

First, the judgment’s full import can be understood when juxtaposed with the American Supreme Court’s judgment in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission in 2010. In Citizens United, the American Supreme Court had held, by a 5-4 majority, that the First Amendment to the United States Constitution bars any limits on corporate expenditure towards elections. Justice Kennedy, writing for the majority, had held that the First Amendment does not distinguish between political speech by natural persons and corporations, rejecting the argument that the invalidation of such a bar would, among other things, distort the political process and breed corruption. This judgment has been sharply criticized for sanctioning unlimited corporate funding in the electoral process, thus undermining its purity and fairness (for instance, see Ronald Dworkin’s criticism, and leading American election law scholar Richard Hasan’s view).

In sharp contrast, the Indian Supreme Court in the Electoral Bonds Judgment underscores the unholy nexus between corporate donations and electoral politics (paragraph 55), and notes that it gives rise to a legitimate possibility of quid pro quo arrangements (paragraph 100) and distorts the promise of political equality held out by the Constitution to every Indian (paragraphs 200 and 201). In a nod to the wrong direction taken by the Citizens United Court, the Indian Supreme Court quotes with approval Justice Stevens’ partly dissenting opinion, holding that the financial resources, legal structure and instrumental orientation of corporations mean that they cannot be treated as being on the same footing as natural persons for evaluating electoral spending limits (paragraph 211).

Second, a notable distinction between Chief Justice Chandrachud’s majority opinion and Justice Khanna’s concurrence is the manner in which the two approach the task of balancing the competing fundamental rights at issue. The Chief Justice finds that the challenge to the Electoral Bonds Scheme and the consequential amendments raise a clash between the right to information of voters under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution and the right to informational privacy of donors, under Article 21 of the Constitution. He then uses the framework of double proportionality to balance the two fundamental rights. Under a traditional proportionality approach, conducted through the single proportionality test, the Court has to examine the fundamental right whose violation is at issue, whether the impugned measure is a suitable means to achieve the stated purpose, whether the impugned measure is the least restrictive means to achieve the stated purpose and whether the impugned measure appropriately balances the violation of the right and the attainment of the stated purpose. The Chief Justice notes that the single proportionality approach is not the best vehicle by which to resolve a conflict between two fundamental rights because it is curated to give primacy to a fundamental right and minimize its infringement to the greatest extent possible [paragraph 153]. He therefore adopts the double proportionality approach which applies when both the fundamental rights at issue have equal apriori weight. In such cases the double proportionality approach assesses whether the impugned measure is proportionate [paragraph 167]. This move makes sense from the standpoint of having a well-structured and neutral pathway to resolve a conflict between two fundamental rights.

Further, the Chief Justice does not clearly distinguish between ‘corporate donors’ and ‘citizen donors’. This clarity is essential from the standpoint of understanding the legal basis for the right to informational privacy of corporate donors. This is crucial given that the notion of ‘corporate citizenship’ is alien to the Indian Constitution and therefore it is not clear how the right to informational privacy can inhere in corporate actors.

On the other hand, Justice Khanna, without recording an express disagreement with the Chief Justice, finds that the right to informational privacy of donors is not attracted by the Electoral Bonds Scheme in the first place. He holds that when a donor makes a contribution through a banking channel to a political party, the factum of such donation is not a secret to the bank and its officials (paragraph 40) and that such information can be accessed by law enforcement agencies and the party in power (paragraphs 41 and 42). He, therefore conducts a single proportionality test, with the traditional four prongs.

Third, another point of disagreement between the Chief Justice’s opinion and that of Justice Khanna relates to the standard used for testing the validity of the amendment to Section 182 of the Companies Act, 2013. This amendment deleted the first proviso to that section, thereby removing any limits on the quantum of electoral funding permissible by companies. While the Chief Justice applies the standard of manifest arbitrariness to hold that the amendment is violative of Article 14 of the Constitution, Justice Khanna holds that manifest arbitrariness is a facet of proportionality (paragraph 73). Justice Khanna justifies this on the basis that the standard of proportionality is founded on the thread of reasonableness, and therefore conduct that is manifestly arbitrary would also be disproportionate.

Does this then mean that any violations of Article 14 must now be tested against the 4-pronged proportionality test, as opposed to the much more straightforward test of manifest arbitrariness? Justice Khanna’s concurrence certainly says so. Again, he makes these observations while agreeing with the Chief Justice. It may be the case that conduct that is found to be manifestly arbitrary may not fail the proportionality test and vice versa, but this issue is left open by the Court for another day.

Fourth, the Chief Justice holds that all fundamental rights are to be read as an integrated whole rather than as separate silos. However, while evaluating the constitutional validity of the impugned provisions, he contradicts himself by using the test of manifest arbitrariness when assessing the deletion of the first proviso to Section 182 of the Companies Act, but not when assessing the validity of the Electoral Bonds Scheme and consequential amendments, especially the removal of the disclosure requirement. It is not clear why provisions like Section 182(3) of the Companies Act relaxing the disclosure obligations on the companies should not also be violative of the doctrine of manifest arbitrariness. The analysis of the Electoral Bonds scheme and consequential amendments from the standpoint of manifest arbitrariness would have not been outcome-determinative, but would have provided the court another angle through which to evaluate the validity of the scheme.

Fifth, Prashant Bhushan, Sanjay Hegde, Shadan Farasat and Kapil Sibal had argued that the nondisclosure of corporate donations by companies violates the fundamental rights of shareholders to information under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, to substantive equality in the decision-making process under Article 14, to exercise their freedom of conscience under Article 25, among other rights. The Court rejected the invitation to go into this issue, reasoning that it had already found that the nondisclosure framework violated the right to know of a citizen and voter, in a larger compass (paragraph 174).

While this reasoning is intuitively appealing, it marks a missed opportunity for the Court to develop the law on fundamental rights of shareholders within companies, so as to ensure that they are able to express their views and choices on a platform of equality. Further, as stated earlier in this post, it is puzzling to note that the Court, without recognizing the fundamental rights of shareholders, goes on to recognize the right to informational privacy of corporate donors. As our Constitution does not recognize corporate citizenship, it is unclear whose fundamental right to informational privacy is at issue.

Justice Khanna holds that the right to privacy of companies can be exercised on very limited grounds, especially by public limited companies, as opposed to private limited companies, sole proprietorships and partnerships, whose right to privacy may be slightly wider (paragraph 73). It would have been interesting to see the Court go into the jurisprudential underpinnings of the fundamental rights of companies and shareholders and develop this theme in this case.

In summation, the Electoral Bonds judgment stands out for its perceptive recognition of the pernicious role of corporate money in politics, its foregrounding of the right to know of the citizens, and its reflections on the tests for evaluating the constitutional validity of the limitations on fundamental rights. The judgment would have benefited from greater clarity on the differences in the approaches adopted by the Chief Justice and Justice Khanna, through a fuller discussion of the fundamental rights of shareholders and how they are implicated in this case and the differences in the tests applied by the Court to find the amendments at issue unconstitutional.

Rahul Bajaj is a practising lawyer in Delhi. Views are strictly personal and must not be attributed to any organization. Dr Jain is a professor of law at NLSIU, Bengaluru.

[Ed Note: This Article has been edited by Sukrut Khandekar and published by Harshitha Adari from the Student Editorial Team.]

[…] Posted byRahul Bajaj and Dr. Sanjay Jain […]

Your blog stands out in a sea of generic and formulaic content Your unique voice and perspective are what keep me coming back for more

This is really interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your magnificent post. Also, I’ve shared your site in my social networks!

Всё понятно, доступно и результат — выше всяких похвал.

Удобно, что есть всё в одном месте.

Van Haberleri, Van Haber | Van Sesi Gazetesi Van Olay, Van Gündem, Van Haber, Van haberleri, Gündem haberleri, van erciş, van gevaş, van edremit

Perpa Kameram | Güvenlik Kameraları gizli kamera, kamera sistemleri, güvenlik sistemleri

Looking forward to your next post. Keep up the good work!