Introduction

“The Indian audiences have of course come of age from the times of two flowers cuddling each other symbolizing male and female union to more explicit manners of displaying such activity.”-Ekta Kapoor v. State of Madhya Pradesh

Who would have thought that messages like “I like you”, “you are slim” could be labelled as obscene by a sessions court? To provide some context, the statements were not made in a conservative setting but in a social setting in Mumbai, a city known for having open-minded values generally. While the above statements may be unwarranted and its timing (around midnight) obviously raises eyebrows, the question remains if this could amount to a criminal offense of obscenity? “Obscenity” has become a new buzzword, entering both courtrooms and social discourse, with high profile cases such as those involving Ranveer Allahbadia and Samay Raina propelling the debate into the national spotlight.

In this piece, we offer a different perspective as to how and on what basis a material should be labelled as obscene, underscoring the idea that it’s time to rethink the definition of obscenity.

Debunking the Community Standard Test

In 2014, a monumental shift occurred with the landmark case of Aveek Sarkar v. State of West Bengal, in which the Supreme Court of India decided to do away with the archaic Hicklin Test and adopted the more progressive Community Standards Test, which was one of the prongs established in the landmark U.S. case of Roth v. United States. The erstwhile Hicklin Test judged material based on whether isolated portions could corrupt the most vulnerable. On the other hand, the Community Standards Test determines that a material is obscene if, according to the contemporary standards, it appeals to the prurient interests in a patently offensive way, lacking serious artistic, scientific, and literary value.

A. “Community” in the Community Standard Test

While the Community Standards Test marked a progressive transition in India’s obscenity jurisprudence, its implementation till now has been riddled with critical issues. A major concern lies in defining what constitutes the “community” in the Community Standards Test. The Canadian Supreme Court, in R. v. Labaye, rejected the concept of community standards on the ground that a community cannot be objectively defined. The Court, while acquitting Jean Labaye for operating a swinger club, ruled that consensual acts without criminal or actual harm cannot be deemed as obscene. Based upon this, the Court observed that people belonging to different age groups, culture, and region may perceive things differently.

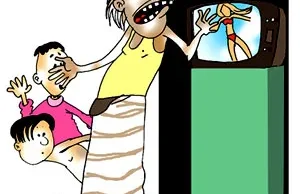

The issue with identifying the community on whose standards obscenity should be judged is enhanced in India, due to its diversity, as acknowledged in the case of Ajay Goswami v. Union of India. The Court was examining a crucial question of whether there is a need for excessive restrictions on newspapers because some articles may deprave and corrupt the minds of young and adolescent. While rejecting the petition seeking these restrictions, the Apex Court observed that determination of obscenity is highly subjective owing to varied standards, cultural backgrounds, and individual sensitivity.

B. Community Standards: National or Local?

The other inherent key dilemma: the national vs. local standard debate. People across India live starkly different lives; the urban and rural lifestyles and moral values are distinct. The idea of a uniform national standard is problematic in that sense, as it cannot capture the nuances of regional moral perceptions. What is acceptable in one region may be considered highly offensive in another.

For instance, the “Kiss of Love” campaign highlighted the stark divide of perceiving the standard of morality and obscenity across India. The campaign started in 2014, where young people initiated a protest after a moral policing incident where a couple was harassed for kissing in public. While many in the urban areas supported it as an assertion of personal freedom, conservative groups labelled it as obscene and against Indian culture.

On the flip side, if obscenity laws are to be applied based on localised community standards, the question remains as to how should “local standards” be defined, whether on geographical or cultural or religion basis? Furthermore, if different regions were to adopt different benchmarks for obscenity, it would result in varying levels of constitutional protection for speech and expression. In addition to this, in the era of internet and social media, the local standard appears to be under particular strain since the content audience transcends regional boundaries.

The Inconsistent Application of “Community Standards Test” By Indian Courts

The most pressing concern revolving around the current community standard test lies not only in the structural doctrine of the test but also in how the judiciary interprets and applies it. For instance, Justice Surya Kant’s oral remarks criticising Allahbadia’s “quality of humour,” describing it as filthy and unfit for family viewing. These remarks reflect a subjective moral view rather than an application of an objective legal standard. Crucially, the show in which Allahbadia made these remarks was a paid, subscription-based program, meaning viewers consented to its content with full awareness of its nature.

A stark contrast to this judicial approach can be found in a 2018 Kerala High Court ruling concerning a magazine cover depicting a mother breastfeeding her child, an artwork created by renowned artist William Dalrymple. In this case, Chief Justice Antony Dominic observed, “One man’s vulgarity is another man’s lyric”. This statement reflects a more nuanced and liberal understanding of obscenity that acknowledges the subjective nature of artistic interpretation.

Similarly, in Apoorva Arora v. State, Justice Narasimha observed: “While a person may find vulgar and expletive-filled language to be distasteful, unpalatable, uncivil, and improper, that by itself is not sufficient to be ‘obscene’.” This approach sharply diverges from Justice Kant’s in the Allahbadia case and underscores the inconsistency in judicial approaches to obscenity in India. While some judges have relied on their subjective opinion of the content, other judges have looked at the content from the perspective of the intended audience and the context in which the statements were made.

In the next Part, the authors make a principled case for consistently applying the contextual assessment of obscenity.

[Ed Note: This piece was edited by Hamza Khan and published by Baibhav Mishra from the Student Editorial Team.]