Blurb: Building on the foundation laid by S.R. Bommai and the Article 370 judgment, this part analyses the “object and purpose” test as a standard for evaluating the constitutionality of actions taken after a valid proclamation, assessing its application to the abrogation of Article 370 and the bifurcation of Jammu and Kashmir. It is argued that, while the test offers a robust framework for curtailing the misuse of emergency powers, its inconsistent application raises questions about the thoroughness of judicial intervention in safeguarding federal principles.

Introduction

In Part I of this piece, I elaborated the nature of Article 356 and the extent of judicial review of the Executive’s actions under a regional emergency. In this part, I elaborate on the ‘object and purpose’ test which is laid down in the Article 370 judgment and argue that it’s application was inconsistent in the case of the reorganization of the State of Jammu and Kashmir.

The “Object and Purpose Test”

The object and purpose test as set out in the Article 370 judgment is that the exercise of power by the President under Article 356 must have a reasonable nexus to the object of the Proclamation. Such a check on the use of powers is necessary to curtail misuse of the exceptional powers, but at the same time allow for the use of the said powers if it is necessary to further the object of the proclamation. Thus, according to the said test, if the actions taken by the President or the Union under sub-clauses (a), (b) and (c) of Article 356(1) and under Article 357 are not relevant to achieving the purposes of the Proclamation, they can be considered invalid. However, the exercise of power by the President for everyday administration of the State is not ordinarily subject to judicial review.

Now, questions may arise as to whether the said application of the test is constitutional. I answer in the affirmative for two reasons. Firstly, as already noted, in Bommai the court held that irrevocable actions cannot be taken by the President before the approval of the Parliament of the Promulgation. This too is a restriction on the extent of the use of powers by the President. Secondly, unlike clauses (a) and (b) which deal with specific powers, clause (c) is worded broadly. It encapsulates the power to make “incidental and consequential provisions” to give effect to the object of the Proclamation (¶203). I argue that powers under clauses (a) and (b) can be derived from clause (c) itself (¶140, In re Article 370). That being the case, all powers under Article 356(1) must be read with the restriction under clause (c). Therefore any action taken must be necessary or desirable to give effect to the objects of the Proclamation.

The power conferred by Article 356 upon the President is exceptional and designed to ensure that the Government of the States is carried on as per the Constitution. The rationale behind the said power is to ensure the restoration of smooth functioning of the state machinery in cases of exigencies. Thus, it is an important power. However, such a power has been historically misused in multiple instances to further political ends.

First, the framers’ intent of the emergency powers becomes important here. Dr. BR Ambedkar recognized the exceptional nature of the powers and hoped that the power under Article 356 would never be called into operation and that it would remain a dead letter. The Constituent Assembly hoped that the power under Article 356 would only be used in extraordinary situations, however by the time Bommai happened, the proclamation was used over ninety times. Thus, it was evident that the powers were prone to misuse. While the Wednusbury Standard in Bommai has addressed the issue of misuse of Article 356 to a certain extent, it is only limited to the validity of the proclamation itself. Thus the reasonable nexus standard further strengthens the system by providing for intervention in curtailing misuse of the provision after a valid promulgation.

Second, even if we consider that exceptional decisions must be taken, the availability and choice of these alternatives must depend on the nature of the constitutional crisis, its causes and the exigencies of the situation. Article 356 is not intended to grant unlimited powers to the President but is confined to the necessary measures required to address the specific crisis at hand (Bommai, ¶157). While the Executive is trusted to exercise these powers judiciously, any actions taken that are not necessary or desirable to achieve the intended purpose cannot be considered free from scrutiny or consequences.

Was the “Object and Purpose” test met in the Article 370 case?

In this part, I argue that while the standard for judicial review and the object and purpose test set out by the Court in the Article 370 case are valid, the implications of the decision in the case are indeed not. Firstly, I analyze whether the test was rightly applied in the question of the constitutionality of the abrogation of Article 370. And, secondly, I argue that the test was not rightly applied while determining the validity of the bifurcation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

i. Whether the Abrogation of Article 370 satisfies the “object and purpose” test.

As noted, the standard for checking whether an action taken was subject to judicial review is mala fide or extraneous. In the present case, the court held that this standard was not met. It has previously been argued that the abrogation of Article 370 was neither “necessary” nor “desirable” to give effect to the object of the Proclamation. The contention raised is that, in the present case, the proclamation under Article 356 was issued due to the political vacuum crisis. Thus, it has been argued that the object of the Proclamation was only to ensure stable continuity in governance and administration of the State. I argue that this contention might untenable for two reasons.

Firstly, the question of mala fide does not arise in the present case as the powers exercised by the President to abrogate Article 370 were not dependent or consequential to the imposition of Article 356. Since the court held that the President had the absolute power to abrogate the provision, the action cannot be mala fide.

Secondly, the argument that the abrogation of Article 370 was not relevant and necessary to further the object of the Proclamation can be contended. This is because, while the initial promulgation was issued due to political instability created by the resignation of the Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, the reasons stated for the extension of the promulgation were violence and security constraints. The stated purpose in the legislature for the abrogation being national security, it can be said that the action taken does not meet the extraneous or irrelevance standard. This is because the Wednesbury standard is only limited to testing whether the action taken is relevant and rational and not whether it is proportional.

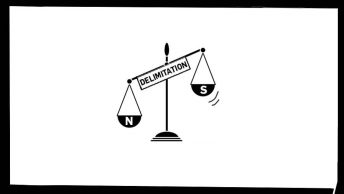

ii. Whether the bifurcation of the State of Jammu and Kashmir satisfies the “object and purpose” test.

In exercise of the power under Article 356, the President, inter alia: (a) assumed to himself all the functions of the Government of the State and all the powers exercisable by the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir; (b) declared that the powers of the Legislature shall be exercisable by or under the authority of Parliament; and (c) suspended the first and second proviso to Article 3.

In the present case, the proviso to Article 3 was suspended by the Proclamation and the Act of Parliament expressed its views in support of the Reorganisation Act. The question that arises is whether the said action was done in furtherance of the purpose of the Proclamation. I answer in the negative.

The first proviso to Article 3 requires the President to refer any Bill affecting a state’s area, boundaries, or name to that State’s Legislature for feedback. However, in the case of the Reorganisation Bill, the President referred it to the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha because Parliament, under Article 356’s Proclamation, had assumed the powers of the Jammu and Kashmir Legislature (¶507). The issue before the court was whether the Parliament could substitute its own views for the views of the State legislature as required under the proviso to Article 3 given the power conferred upon it by the Proclamation issued under Article 356.

The court holds that the object and purpose test is met, and the impugned action is not justiciable for the reason that there was no mala fide. The court reasons that since the views of the Legislature of the State under the first proviso to Article 3 are recommendatory to begin with, Parliament’s exercise of power under the first proviso to Article 3 is valid and not mala fide. However, the court fails to apply the very test it set out for justiciability as it does not check whether the actions were extraneous to the purpose of the Proclamation.

The Reorganisation Bill in its objects and purpose only states that it is an Act to provide for the reorganisation of the existing State of Jammu and Kashmir and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. There is no mention or reference to the national security or political breakdown of the constitutional machinery in the state as being the reason for the reorganisation. Thus, the same cannot be said to be desirable or necessary for the purposes of restoring the constitutional order.

Further, the second proviso to Article 3 read that a Bill providing for increasing or diminishing the area of the State of Jammu and Kashmir or altering the name or boundary of the State cannot be introduced in Parliament without the consent of the legislature of the State. Thus, the powers of the State legislature in the present case were not merely discretionary. However, the court concluded that CO 272, granting the President power under Article 370(1)(d) to apply “all or part of the Constitution” to Jammu and Kashmir, is valid. As a result, exceptions and modifications to the Constitution’s application in Jammu and Kashmir ceased to exist.

Even if we were to take the second proviso to cease to exist, I argue that in the present case, while the power under proviso one is recommendatory, it is still a power that the State Legislature holds. This being the case, the Parliament can exercise such discretion on behalf of the State only when it assumes powers of the state legislature as per Article 356(1)(b). Whether such power is used to further the object of the proclamation hence becomes important to meet the test set out. In the present case, the court fails to address the relevancy of the bifurcation to fulfill the object of the Proclamation.

While the said concern might not have affected the decision of the court on the validity of the Promulgation due to the CO 272, the application of the extraneous standard has wide-ranging implications for the jurisprudence on the power of courts to review the extent of actions taken by the President. While the court sets out the right standards, it fails to implement the same to the extent that it sets out.

Conclusion

This paper has critically examined the scope and application of Article 356 in light of the Supreme Court’s recent decision in the Article 370 case and the landmark judgment in S.R. Bommai vs. Union of India. By delving into the powers conferred upon the President and Parliament during a Proclamation under Article 356, and the subsequent scope of judicial review, several key conclusions have been drawn.

Firstly, the analysis established that while the Bommai case primarily focused on the validity of the Proclamation itself, the Article 370 case extended this review to include actions taken post-Proclamation. It is clear that judicial review, as shaped by Bommai, encompasses not only the legality of the Proclamation but also the actions taken under it. The Article 370 case affirmed this broader scope, setting a precedent that the President’s and Parliament’s actions post-proclamation must align with the constitutional purpose of Article 356.

Secondly, I introduced and applied the “object and purpose” test to evaluate the constitutionality of actions taken under Article 356. This test is crucial in ensuring that actions remain relevant to the Proclamation’s objectives and prevent misuse of emergency powers. The findings indicate that while the test was rightly applied to the abrogation of Article 370, it was not adequately applied to the bifurcation of Jammu and Kashmir. The court’s failure to assess the relevance of bifurcation to the Proclamation’s object raises concerns about the consistency and thoroughness of judicial review in this context.

ueoOvbRJTe2

İstanbul, Türkiye’nin ekonomik ve ticari merkezi olarak, hem bireylerin hem de şirketlerin vergi yükümlülüklerinin oldukça yoğun olduğu bir şehirdir. Vergi mevzuatındaki karmaşık düzenlemeler ve sık sık yapılan değişiklikler, mükelleflerin zaman zaman hukuki desteğe ihtiyaç duymasına yol açmaktadır. İstanbul vergi avukatları, hem gerçek hem tüzel kişilere, vergi uyuşmazlıklarında profesyonel danışmanlık ve temsil hizmeti sunarak, olası cezaların ve kayıpların önüne geçilmesine yardımcı olur.