This post is part of a series on constitutional and political questions relevant to contemporary times written by Sughosh Joshi, who is working on civic education and engagement. Sughosh also publishes a weekly substack newsletter called ‘In the Matter of the Republic’, you can check it out here and subscribe to it for regular updates.

The previous part of this series focused on the historical antecedents to the post of Governors of states. We looked at how they were agents of colonial rule for the East India Company and then the British Government. This legacy was intended to be ended by the Constitution if not for the experience of the partition leading to a strong centre. As a result, the Governors in independent India found themselves bearing two caps – one of the agent of the Central Government and another of the symbolic head of a state, bound by the aid and advise of the Council of Ministers.

This part shall focus on how Governors have managed these caps, often donning the Central Government’s colours more than their states’. However, before that, it is important to set the stage with making clear the final Constitutional position of a Governor and their role in the state.

Constitutional Position of Governor

Article 153 provides for the position of a Governor of a state. Article 155 provides for the President to appoint Governors. Article 156 provides that a Governor shall serve at the pleasure of the President. Article 163 requires the Governor to act in accordance with the aid and advise of the Council of Ministers except for carrying out functions which require the exercise of the Governor’s discretion. However, the Constitution does not explicitly mention where such discretion is to be exercised.

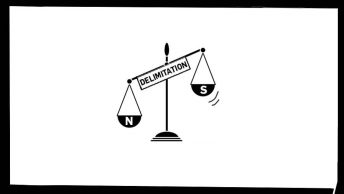

In sum, a Governor is an appointee of the Central Government with little guarantee of tenure and expected to act as per the aid and advise of the state Government but with the potential to exercise discretion which is undefined.

Extent of Discretion

The Justice Sarkaria Commission was appointed in 1983 with a mandate to study and suggest frameworks for Centre-State relations in the country. The Commission outlined the role of the Governor, specifically the discretionary powers. After carefully studying Constitutional provisions and the experience of the Republic till that point, the Commission made a list of situations which ‘may require exercise of discretion’. These include appointment of Chief Minister, dismissal of Chief Minister, summoning, proroguing and dissolving the Legislative Assembly when the Council of Ministers does not enjoy majority, returning bills to the state legislature for reconsideration or reserving bills for the President’s assent, and sending a report to President under Article 356. The Commission also observed instances where the Constitution requires Governors to act of their own accord – special provisions relating to states in the North-East, for Scheduled Areas and for Backward Areas within states such as Maharashtra and Gujarat. The Commission Report also provided several recommendations with respect to the exercise of discretionary powers by Governors.

Therefore, broadly, there are two arenas in which the Governor is required to exercise discretion – the political and the legislative. The political arena includes appointment and dismissal of Chief Minister, summoning, proroguing and dissolving the Legislative Assembly when the Council of Ministers does not enjoy majority, and sending a report to President under Article 356. The legislative arena includes returning bills to the state legislature for reconsideration or reserving bills for the President’s assent.

Political Arena – Judicial View

Appointment and Dismissal of Chief Ministers

First, the exercise of discretion in appointment and dismissal of Chief Ministers arises out of circumstances in which no single party has a majority or a party or coalition which has majority subsequently loses it. Controversies around this are commonplace, with the first involving the (then) Madras in 1952 and the latest being Maharashtra in 2019 with several others in the years gone. Although the Sarkaria Commission suggested a sequence to be followed in inviting leaders of political parties to form governments, it is as such not binding.

Eventually, due to the failure of the office of the Governor to maintain the dignity of the office has forced Courts to intervene in such cases. For the first time in the case of Jharkhand Anil Kumar Jha v. Union of India in 2005 and subsequently in several cases for Arunachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, etc., the Supreme Court has laid down a scheme for appointment and dismissal of Chief Ministers. In contentious cases, where majority of a party or pre-election coalition is not clear, appointment of Chief Ministers must ordinarily be followed by a floor test to prove majority. Similarly, when a claim of loss of majority of an incumbent government is made, Courts have ordered floor tests to test such claims, before the Governor makes a decision on removal of a Chief Minister.

President’s Rule

Governors have always been used by the Central Government to remove state governments not aligned to their politics by recommending President’s Rule under Article 356. Examples start from 1959 where a democratically elected communist government in Kerala was dismissed for a perceived ‘subversion of democracy’ to 2019 where President’s rule was imposed and removed at the drop of a hat in Maharashtra. The two cases which mark the territory of intervention of Courts in proclamations of Presidents’ Rule under Article 356 were a wholesale dismissal of state governments by the Central Government.

First, in 1978 after the Janata Party became the first non-Congress Central Government, it dismissed all Congress state governments claiming that they had lost the ‘moral authority’ of continuing in office considering the party’s defeat in the General Election to the Lok Sabha. This led to the case of State of Rajasthan v. Union of India, where the Supreme Court held that it was fundamentally a political question and proclamations under Article 356 could only be challenged in case there was mala fide involved or the declaration was based on extraneous or irrelevant grounds.

Second, in 1992 after the demolition of Babri Masjid and subsequent riots, three BJP governments in Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan, and three others in Karnataka, Meghalaya and Nagaland were dismissed using the proclamation under Article 356. S. R. Bommai v. Union of India was decided by a 9-judge bench and while a few judges tried to increase the burden on the Central Government to prove bona fides of a Presidential declaration, the position has largely remained the same as State of Rajasthan. However, this case strongly established the requirement of conducting a floor test before dismissing a government.

Legislative Arena – Judicial View

Assent to bills

A controversy attracting relatively lesser attention, this question goes to the heart of the role of a Governor in a system of responsible government. The Constitution provides a choice to the Governor to provide assent to bills passed by the state legislature, to return the bills to the legislature for reconsideration, or to reserve assent of the President.

In ordinary circumstances, Governors assent to bills passed by the legislature. However, in recent times, it has been observed that Governors have withheld assent to bills without returning them to the legislature for reconsideration. The latest case, State of Punjab v. Principal Secretary to the Governor of Punjab, which opened this series in the previous post, clarifies this question. The Court has held that Article 200 of the Constitution does not provide power to the Governor to indefinitely withhold assent to bills. It read the scheme of Article 200 in a way that requires the Governor to return a bill to the state legislature for reconsideration as a logical consequence of the decision to withhold assent to that bill. However, the Governor is bound to provide assent to the bill, irrespective of any changes, after reconsideration of the legislature.

Conclusion – Reforms

A fundamental argument of those who have given any thought to the question of Governors is that the problem lies in the procedure of appointment and removals and a lack of certainty with respect to the tenure of the Governor. Others have called for the abolition of the post altogether. However, the actions of any Governor are essentially a design flaw. The creation of the post created with it competing interests which the Governor would have to bear in mind. While a Governor must be pliant to the aid and advise to the Council of Ministers in regular circumstances, they cannot be under the fear of removal by the state authorities creating a chilling effect on their ability to report breakdown of constitutional machinery to the President.

In order to create an office which acts in a balanced manner would require two changes. First, changes to the appointment of Governors that considers views of the State Government, leading to the appointment of non-partisan persons uninterested in party politics. Second, changes in the removal of the Governors, guarding them from the ‘displeasure’ of the President yet providing the state authorities some method to express their ‘displeasure’ of the Governor.

Sughosh is working on civic education and engagement. He is deeply interested in Constitutional Law, Politics and Policy. He graduated from NALSAR University of Law.

[…] Posted bySughosh Joshi […]