This post is part of a series on constitutional and political questions relevant to contemporary times written by Sughosh Joshi, who is working on civic education and engagement. Sughosh also publishes a weekly substack newsletter called ‘In the Matter of the Republic’, you can check it out here and subscribe to it for regular updates.

Governors of States are by definition, ‘Excellent’, rarely so in practice. The Supreme Court recently delivered a judgment on the tussle between the Governor of Punjab and the Government of Punjab (more specifically, between the Governor and the Council of Ministers). As an aside, it is important to appreciate that the judgment is one of the shorter ones delivered in recent history; only 27 pages! The issue at hand in the case was the refusal of the Governor to assent to bills passed during an Assembly session in June, based on ‘legal advice’ received by him which stated that the said session was illegitimate and illegal.

Apart from this case, there are several examples of appointed Governors and elected Councils of Ministers of different states at loggerheads. The Supreme Court is currently hearing disputes from Kerala and Tamil Nadu. At the heart of the issue is the position and powers of Governors within the framework of the Constitution. This shall be a two-post-series. This post shall explain the history of Governors – the colonial legacy, the discussions in the Constituent Assembly – and the final position of Governors as per the Constitution. The next post shall focus on the post-independence experience and the resultant cases, as well as suggested reforms of the powers and functions of Governors.

Governors in Colonial India

India was introduced to the term ‘Governor’ through appointees of the East India Company (EIC) by that name who acted as administrative heads, exerting power over the governance of employees. Later, military powers were extended to the Governors. The Governors would also have ‘Councils’ to advise them. With the EIC’s territorial conquests, the British Parliament intervened through the Regulating Act of 1773. It created a hierarchy of Governors, with the Governor at Fort Williams, Calcutta being rechristened the Governor General of India. Other Governors – at Bombay and Madras would be subordinate to the Governor General of India. This Act also provided legislative powers to the Governors. Subsequent interventions by the Parliament adjusted this scheme in different ways.

After the British Crown took absolute control over the government of India in 1858, wholesale changes were brought to the role and powers of Governors. The first changes were introduced in 1861 when legislative procedure was brought in line with British Parliamentary practice, with Governors needing to assent to legislation. The Councils of Governors were expanded, especially for legislative functions. Non-official members were to be nominated and involved in making legislation. However, Governors and the Governor General would reign supreme with the potential to veto any legislation.

The Government of India Act, 1919 was the first attempt at providing a greater degree of autonomy to Indians in the governance of the region. Legislative powers were to be devolved to Ministries nominated by the Governor from the Council now consisting of 70% elected members. However, control over important ‘reserved’ subjects as well as unbridled veto power continued to rest with the Governor.

The Government of India Act, 1935 provided greater autonomy to Indians with Ministries being given far broader control over subjects on which provinces could make laws. The Governor, however, continued to exercise discretionary power as well as make decisions as per individual judgment even in areas under jurisdiction of Ministries. The office of the Governor continued to be a site of colonial control of the provinces.

To be or not to be: Governors in a post-independence India

The Constituent Assembly spent significant time discussing the position of a Governor in independent India. In sight of the colonial experience of the office of Governors, the Constituent Assembly discussed the appointment and removal of Governors as well as discretionary powers given to them.

The discussion surrounding appointment of Governors was initially limited to the manner of election of the Governor – whether directly elected by the people or indirectly by the members of the state assembly (akin to the election of the President). As the provisions for appointment of Governors were then discussed two years later, in 1949, the experiences of the partition loomed large on the minds of members of the Constituent Assembly. Any mechanism of election of a Governor would mean a local person becoming the Governor of a state. It was feared that such a system would encourage secessionist tendencies within states. According to Jawaharlal Nehru, Governors were to now be seen as agents of national reconstruction. While adopting the appointment of Governors by Presidents, it was hoped that some conventions would be developed regarding these appointments – that the appointees would belong to other states, the state governments would be consulted in the appointment, and the appointees would not be involved in party politics. However, these were not incorporated in the written text of the Constitution.

The Constituent Assembly also discussed removal of the Governor. While the Assembly was considering the appointment of Governors through elections, the proposed mechanism for removal of Governors was like that of impeachment of the President. However, as the mechanism of appointment changed, so did that of removal. The new system of appointment would be accompanied by Governors serving at the pleasure of the President. This was criticised as affecting the independence of the Governor, with them being a pawn in the hands of the President, that is the Central Government.

The Governors’ discretionary powers, adopted from the Government of India Act, 1935 were severely constrained to only certain areas. These included appointment and dismissal of ministers, summoning the state legislature, returning bills to the state legislature, issuing of proclamation of emergency, etc. – basically, for those situations in which acting according to the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers would be counter-productive. The draft articles for these aforesaid aspects included an explicit provision that these shall be in exercise of Governors’ discretion. However, all references to the exercise of discretion were omitted from the draft later. As a result, Article 163 which makes aid and advice of the Council of Ministers binding on the Governors, except those which require the exercise of their jurisdiction, is left without any explicit parallel provisions requiring such exercise.

Conclusion

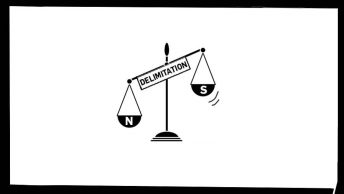

A product of colonial legacy, the office of the Governor suffers from a fundamental tension between two roles that have been accorded to it. First, the role as an agent of the Central Government, acting as a bridge between the state and the Centre. Second, as the symbolic head of a State, bound to act in accordance with the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers. The Constituent Assembly was hopeful of the development of conventions and relied on the goodness of people who would assume the role and left a lot unexplained in the text of the Constitution.

With core political and administrative functions to be carried out and little guidance on the limits of discretion, there have been numerous instances of questionable decision-making by Governors since the creation of the office. The next part shall explore these examples as well as the resultant cases taken up by courts. It will also look at suggestions by scholars on reforms needed.

P.S. Major parts of this post have been taken from the book ‘Heads Held High: Salvaging State Governors for 21st Century India’ by Shankar Narayanan, Kevin James, and Lalit Panda and published by Navi Books. You can read it here for a more detailed account.

Sughosh is working on civic education and engagement. He is deeply interested in Constitutional Law, Politics and Policy. He graduated from NALSAR University of Law.

[…] Posted bySughosh Joshi […]