Introduction

We are now four months away from the second anniversary of the Supreme Court of India’s (SC) ruling upholding the abrogation of Article 370 of the Constitution. While affirming the constitutional validity of the abrogation, the SC also issued sweeping directives calling for constitutional, political, and social reforms in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). Chief among these was a mandate to conduct elections in the region and to restore its statehood at the earliest practicable opportunity. While elections have since been held in the union territory and a government formed under Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, the promise of restoring statehood remains unfulfilled for its citizens.

This piece intends to draw attention to a piece of that judgment that has gone largely unimplemented – a greener patch seemingly abandoned amidst the political tumult that ensued. In his concurring opinion, Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul, the sole Kashmiri on the Constitutional Bench, emphasised reconciliation over mere legal finality and proposed the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (T&RC) to investigate human rights violations committed by both State and non-State actors in Kashmir since the 1980s.

This is not the first time a T&RC has been proposed in Kashmir. Omar Abdullah first floated the institution back in 2007 – to investigate violations by security forces and militants and to “correct the black history” of Kashmir’s insurgency. Although he won that election and governed the region for six years thereafter, the promised Commission never moved beyond mere lip service.

Likewise, while Justice Kaul’s recommendation received an initial spurt of media attention and public interest, no such Commission has materialised a year and a half later. This piece examines two interrelated questions: First, what is the legal nature and jurisprudential weight of Justice Kaul’s recommendation? Second, does our understanding of J&K’s complex historical tragedies allow us to carve a space for the transitional justice that a T&RC stands for?

Judicial Suggestion or Binding Direction?

Though couched initially in the recommendatory language, Justice Kaul’s proposal-“I recommend the setting up of an impartial Truth and Reconciliation Commission,”- becomes more definitive as it progresses with more assertive phraseology – “the Commission will investigate and report on the violations of human rights and recommend measures for reconciliation”, and for this to be done “expediently, before memory escapes.”

To understand the legal weight of such language, one must read these comments in the broader jurisprudential context within which it is embedded. Justice Kaul invokes the principle of transformative constitutionalism, positioning the judiciary as a ‘responder to social demands of the polity to offer flexible remedies’. In support, he refers to Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan (1997), where the Court laid down binding guidelines in the absence of legislation on sexual harassment at the workplace. One must remember that under Article 142, the SC has the power to pass any decree or order as would be necessary to deliver ‘complete justice’ in any cause or matter pending before it.

Justice Kaul’s invocation of Vishaka may perhaps indicate his intention to imbue the recommendation with binding effect. Conversely, it may also be argued that Justice Kaul’s reluctance to mention Article 142 may indicate otherwise . Notably, the Vishaka judgement itself does not even have a single mention of Article 142, but rather weaves Article 32 and 141 together to hold its guidelines binding. Taking a thread, we feel that the former interpretation accords more weight than its contender.

Thus, we argue that the recommendation for T&RC is reinforced by a jurisprudential force that goes beyond mere “advice” yet stops rather abruptly and anticlimactically short of articulating any implementation mechanism, institutional composition, or statutory framework. We are forced to wonder if this is a deliberate gesture of judicial restraint in a politically sensitive domain.

The Question of Implementation

Justice Kaul leaves it to “the Government” to “devise the manner” in which the T&RC should be constituted. This, again, leads to inevitable ambiguity. The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019, limits the powers of the newly created Legislative Assembly of the Union Territory. Under Section 32, it cannot legislate on matters relating to “public order” and “police” – central concerns in any human rights hearing, let alone investigation. Zooming out, even the VII Schedule of the Constitution, through List III, Entry 11A, seems to suggest that the power to create such judicial bodies/quasi-judicial institutions lies with the Union and the States, ousting the possibility of the ‘Union Territory’ of J&K ever being legislatively competent to actualise this recommendation by itself.

Therefore, so long as it remains reluctant to allow resumption of Statehood to J&K, the creation of a T&RC lies at the mercy of the Central Government. However, neither has the Centre announced such intent, nor have funds been allocated towards this Commission. Legislative will is absent where the constitutional competence for this scheme lies.

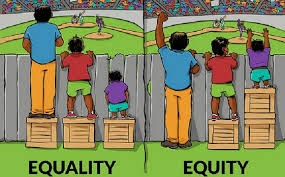

More importantly, should such a will ever arise, can a centrally constituted body capture Kashmir’s complex cultural, religious, and historical dynamics? From a normative perspective, such commissions work best when they emerge from grassroots legitimacy and local political ownership. Currently, J&K’s elected representation in the Indian Parliament constitutes less than 1% of its total strength, giving it no democratic agency over any centralised decision made on its behalf. A bottom-up assimilation of intentions, resolve, and direction that can claim the closest semblance to democratic legitimacy can only arise from a Commission made by the people of J&K for themselves. To that end, the Statehood of J&K must be restored. Before memory escapes – as the SC presciently warned.

A Commission of What Kind? Design and Precedents

In the hypothetical that the aforementioned challenges are glazed over and the Parliament resolves to create a well-thought-out, contextual and demographically-sensitive body in line with this judicial directive, what must it look like?

A look into history shows us that whenever T&RCs have been deployed globally to address historical injustices – from apartheid in South Africa to the residential school system in Canada – intense care and caution have been exercised. South Africa’s T&RC, for instance, constituted under the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act (1995), was designed explicitly “not to prosecute” but “to document truth and promote healing.” It televised hearings, granted conditional amnesties, and was led by Desmond Tutu, a figure of moral legitimacy on both sides of the aisle.

The SC has previously refused to entertain petitions seeking a Special Investigation Team probe into the Pandit exodus. In that context, Justice Kaul’s recommendation seems like a creative workaround – a form of state-sponsored testimony-gathering rather than adversarial prosecution. However, by stopping short of laying a few directive guidelines, guardrails and timelines to actualise his vision, Justice Kaul has intentionally thrown his baby out with the bathwater. Perhaps he knew of the sheer impossibility of this idea and merely voiced an ideal solution that he felt, in his heart, would have healed wounds and built bridges – in a more accepting, inclusive and less divided India.

Justice Kaul invokes this South African model and quotes Justice Albie Sachs, who described the T&RC process as not one of accusation but of catharsis:

“Judges do not cry. Archbishop Tutu cried […] It was an intensely human and personalised body, there to hear in an appropriately dignified setting what people had been through.”

Applying this template to J&K raises further difficulties. Unlike apartheid, which has one enemy, i.e. racism, the nature and facts of the Kashmiri conflict are complex and dissonant, where there is no universal enemy and each party, including the State, “others” as one another. The 1990 exodus of Kashmiri Pandits is well-documented, but its scale and causes remain contested. Different actors have been alternately blamed, ranging from Islamic militants to Pakistan-backed insurgents to State authorities themselves. Former Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah has claimed that Muslims too were victims, and that Governor Jagmohan “facilitated” the Pandit migration under promises of safety and return. Others strongly defend Jagmohan’s actions as a life-saving intervention. Estimates of displaced Pandits range from academic projections of 160,000 to exaggerated claims of over 450,000 – 700,000. Continuing violations against muslim communities, at the same time, fail to find documentation anywhere. These conflicting accounts, unresolved for decades, show how elusive “the truth” in Kashmir really is.

What Happens When Truth Becomes Political?

We feel there is a compelling reason to exercise much more caution and forethought regarding the possibility of T&RC in India as opposed to the examples cited in the judgment. One recent indicative instance demonstrating the caustic nature of this issue was the polarised popularity of the film The Kashmir Files, which Prime Minister Narendra Modi hailed as a truthful retelling of history (despite historians who claim otherwise). The film was widely seen as a validation of Hindu victimhood. Yet, its public reception was intensely divisive. Many Muslim communities reported a rise in communal rhetoric and violence following the film’s release. There was radio silence against the violence from the cheerleaders of the film. The sense of retribution and vengefulness only seemed to surge post the “revelation of truths.”

This raises critical questions: Can truth-telling in a deeply polarised society remain cathartic? Or does it risk becoming a politically weaponised exercise?

Justice Kaul may have hoped for healing through collective storytelling, but without mechanisms to prevent majoritarian appropriation or media sensationalism, such exercises may deepen fissures instead of uninhibited expression and catharsis. The democratic preconditions for a T&RC – free press, civic dialogue, and mutual recognition of each other’s suffering remain fragile in present-day India.

Moreover, one of the most complex design elements of a T&RC is its composition and method of testimony collection. In South Africa, victims were invited to speak on record; perpetrators could confess in exchange for amnesty. In Canada, Indigenous communities testified over the atrocities of residential schools, with a clear structure for submissions, hearings, and final reports. J&K, however, lacks such a framework. Who will be interviewed? Will the process include militant families, Kashmiri Muslims, displaced Pandits, non-Brahmin Hindus, Army veterans, journalists, and others? What safeguards will exist to prevent re-traumatisation or communal scapegoating? To what extent will the State protect the minorities of today from being persecuted and targeted for the alleged misdeeds of their ancestors? Where shall their truths find a listening ear, and who shall reconcile the pain and peril they endure today?

Even Justice Kaul’s use of the term “impartiality” is contextually thin. In India, many institutions that are meant to be impartial, like the Election Commission, have faced credibility crises. Can any body constituted by the J&K government or even by Parliament claim neutrality in Kashmir, given the polarised positions on the issue held by their respective vote banks? If “truth” is ultimately a product of perception, then any Commission risks being co-opted by one narrative or the other.

More fundamentally, we may not be ready for the truth, as Justice Kaul may have been acutely cognizant. In an environment where one side sees itself as perpetual victims and the other as falsely demonised, any official endorsement of a narrative, no matter how balanced, may trigger backlash. For some, the Commission might be a humanising step. For others, it may reopen wounds or embolden retribution. Until India can hear both stories with equal respect and empathy, reconciliation will remain a deferred dream.

Gokul and Adithi are legal researchers interested in Constitutional law and its critical interaction with science and technology. Gokul currently works at xKDR, and Adithi is at Trilegal.

Ed Note: The piece is edited by Arnav Mathur and published by Vedang Chouhan

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!

Excellent work on this ultimate guide! every paragraph is packed with value. It’s obvious a lot of research and love went into this piece. If your readers want to put these 7 steps into action immediately, we’d be honoured to help: https://meinestadtkleinanzeigen.de/ – Germany’s fastest-growing kleinanzeigen & directory hub. • 100 % free listings • Auto-sync to 50+ local citation partners • Instant push to Google Maps data layer Drop your company profile today and watch the local calls start rolling in. Keep inspiring, and thanks again for raising the bar for German SEO content!

Excellent work on this ultimate guide! every paragraph is packed with value. It’s obvious a lot of research and love went into this piece. If your readers want to put these 7 steps into action immediately, we’d be honoured to help: https://meinestadtkleinanzeigen.de/ – Germany’s fastest-growing kleinanzeigen & directory hub. • 100 % free listings • Auto-sync to 50+ local citation partners • Instant push to Google Maps data layer Drop your company profile today and watch the local calls start rolling in. Keep inspiring, and thanks again for raising the bar for German SEO content!

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!

Excellent work on this ultimate guide! every paragraph is packed with value. It’s obvious a lot of research and love went into this piece. If your readers want to put these 7 steps into action immediately, we’d be honoured to help: https://meinestadtkleinanzeigen.de/ – Germany’s fastest-growing kleinanzeigen & directory hub. • 100 % free listings • Auto-sync to 50+ local citation partners • Instant push to Google Maps data layer Drop your company profile today and watch the local calls start rolling in. Keep inspiring, and thanks again for raising the bar for German SEO content!

Excellent work on this ultimate guide! every paragraph is packed with value. It’s obvious a lot of research and love went into this piece. If your readers want to put these 7 steps into action immediately, we’d be honoured to help: https://meinestadtkleinanzeigen.de/ – Germany’s fastest-growing kleinanzeigen & directory hub. • 100 % free listings • Auto-sync to 50+ local citation partners • Instant push to Google Maps data layer Drop your company profile today and watch the local calls start rolling in. Keep inspiring, and thanks again for raising the bar for German SEO content!

Excellent work on this ultimate guide! every paragraph is packed with value. It’s obvious a lot of research and love went into this piece. If your readers want to put these 7 steps into action immediately, we’d be honoured to help: https://meinestadtkleinanzeigen.de/ – Germany’s fastest-growing kleinanzeigen & directory hub. • 100 % free listings • Auto-sync to 50+ local citation partners • Instant push to Google Maps data layer Drop your company profile today and watch the local calls start rolling in. Keep inspiring, and thanks again for raising the bar for German SEO content!

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!

Fantastic read! I really appreciate how clearly you explained the topic—your writing not only shows expertise but also makes the subject approachable for a wide audience. It’s rare to come across content that feels both insightful and practical at the same time. At explodingbrands.de we run a growing directory site in Germany that features businesses from many different categories. That’s why I truly value articles like yours, because they highlight how knowledge and visibility can create stronger connections between people, services, and opportunities.Keep up the great work—I’ll definitely be checking back for more of your insights!