Part I of the article discussed how A. R. Antulay cannot, even on its own terms, be extended to the POCSO Act. In Part II, the discussion turns to the deeper question of interpretive logic. The problem is not merely that A. R. Antulay was applied beyond its proper context, but that the interpretive method adopted therein admits of reconsideration. When a precedent is invoked to constrain the operation of a social legislation, it becomes necessary to examine not only its reach but also the soundness of the reasoning by which it was reached. It is to that question, of method rather than motive, that the discussion must now turn.

The Difficulty in Accepting SC’s Proposition

It is submitted that there is a need to reconsider A. R. Antulay not only because it reached a cautious conclusion, but because it did so by employing an interpretive methodology that was far from correct.

Firstly, a central methodological flaw in A. R. Antulay is in its treatment of Section 21 of the IPC as a static and self-contained definition, even when deployed through referential legislation. Section 2 of the PC Act, 1947 opens with the words, “For the purposes of this Act”. This prefatory clause is not ornamental. It signals a legislative instruction that once such a reference is made, the borrowed provision is to be read as part and parcel of the later statute, operating in furtherance of its object.

The Court, in effect, read the phrase “for the purposes of this Act” as though it meant “shall have the same meaning as assigned to”, thereby effacing the contextual qualifier embedded in the statutory text and converting a referential adoption into a rigid incorporation.

The Supreme Court itself has consistently recognised the distinction between simple reference and incorporation, and the consequences flowing therefrom, most notably in Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd. v. Union of India. Where provisions are incorporated, they must function within the scheme, purpose, and mischief of the incorporating statute, not as detached historical text.

Antulay ignored this principle. It treated Section 21 IPC as though it were being interpreted for its own sake, rather than as an instrument employed by a preventive statute aimed at cleansing public life. This approach collapses the doctrine of referential legislation into mere textual borrowing, a position doctrinally unsustainable.

Secondly, the PC Act is paradigmatically a mischief-remedying statute. Its concern is not with formal employment status, but with the abuse of public power. Yet in Antulay, the Court did not ask the classical Heydon question: what mischief was Parliament seeking to suppress? Instead, it treated the absence of express reference to legislators as decisive. This is contrary to the Court’s own approach in cases involving socio-economic and regulatory statutes, where purposive construction has been preferred to literal rigidity. In State of M.P. v. M.V. Narasimhan, for example, the Supreme Court expressly held that where two statutes form part of the same system and pursue a common object, definitions may evolve to advance that object.

While penal statutes are ordinarily construed strictly, the Court has repeatedly clarified that this principle is not absolute, particularly where the statute is preventive rather than punitive, and where interpretation concerns the class of persons regulated, not the definition of an offence. In State of Kerala v. Attesse (AIT Corporation), the Court acknowledged that where statutes are interconnected and seek to regulate public conduct, rigid literalism gives way to functional interpretation. Antulay, however, imported the most conservative canon of construction into a statute whose effectiveness depends upon its reach over those wielding public authority.

Thirdly, Antulay adopted a conception of public authority rooted exclusively in executive service of salary, appointment, and departmental control. This is an impoverished understanding of public power, inconsistent with modern constitutional law. Constitutional courts, worldwide, have, on numerous occasions, recognised that function, not form, determines legal responsibility. To insist that public power counts only when exercised from within the executive hierarchy is to ignore the realities of governance, where legislative authority may be more coercive than administrative office.

It may be proper here to submit that a plain reading of Section 21 of the IPC reveals that the provision is framed in inclusive terms, its several clauses serving not as rigid compartments but as descriptive instances of public authority.

Clause “Twelfth”, read with the accompanying Explanations, is of particular significance. It extends to every person either in the service or in the pay of Government, or remunerated for the performance of any public duty. The “or” is disjunctive in nature, and the Explanations make clear that appointment by Government is not a prerequisite. Further, “public duty” denotes any function in the discharge of which the State or the public has a recognised interest.

When so construed, the application to a sitting Member of the Legislative Assembly admits of little difficulty. An MLA is remunerated from the Consolidated Fund of the State under the relevant Salaries and Allowances legislation, and is therefore in the pay of the Government, the disjunctive structure of the clause rendering immaterial the objection that he is not a government servant in the Article 311 sense.

Further, legislative functions of lawmaking, budgetary approval, oversight of the executive, committee work, and redress of public grievances are quintessential public duties, performed on behalf of the State and in the public interest.

The structure and purpose of Section 21 reinforce this conclusion. The provision is deliberately cast wide to encompass holders of public office, and its Explanations remove formalistic barriers which might otherwise defeat its operation.

This reading is consonant with the constitutional position of legislators under Articles 168 – 199 of the Constitution of India, which proceed on the footing that Members of the Legislature hold remunerated public office, even if they do not stand in the service of the executive. Nor does the conceptual distinction between the Legislature and the Government avail the contrary argument, for in the erstwhile IPC, the term “Government” functions as a metonym for the State as a public authority, which remunerates legislators to discharge core State functions.

Take, for example, in committee work, such as that of Public Accounts, Estimates, or Privileges, members are empowered by law to call for information, examine records, and enforce accountability; their role bears a close functional resemblance to other categories expressly enumerated in Section 21.

In any event, Explanation 2 places the matter beyond doubt. A person in actual possession of the position of a public servant is to be treated as such for penal purposes, notwithstanding any technical objection to the manner of his holding office. On this construction, a sitting MLA falls squarely within Clause “Twelfth” of Section 21.

A further indication of legislative intent may be drawn from the post-Nirbhaya amendments of 2013 to the Code of Criminal Procedure, now reflected in Section 218 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita. Section 197 of the Code, which ordinarily requires prior sanction for the prosecution of public servants and judges, was consciously amended to dispense with such sanction where the alleged offence relates to rape or sexual violence. This legislative choice marks a deliberate departure from the logic of institutional protection in cases implicating bodily integrity and sexual autonomy. Viewed in this light, the reasoning in A. R. Antulay, delivered in the confined context of corruption law and sanction-based restraint, cannot readily be extended to confer an analogous protective effect in cases of sexual offences as to do so would be to attribute to the precedent a breadth which subsequent legislative developments have expressly disavowed.

The Way Forward

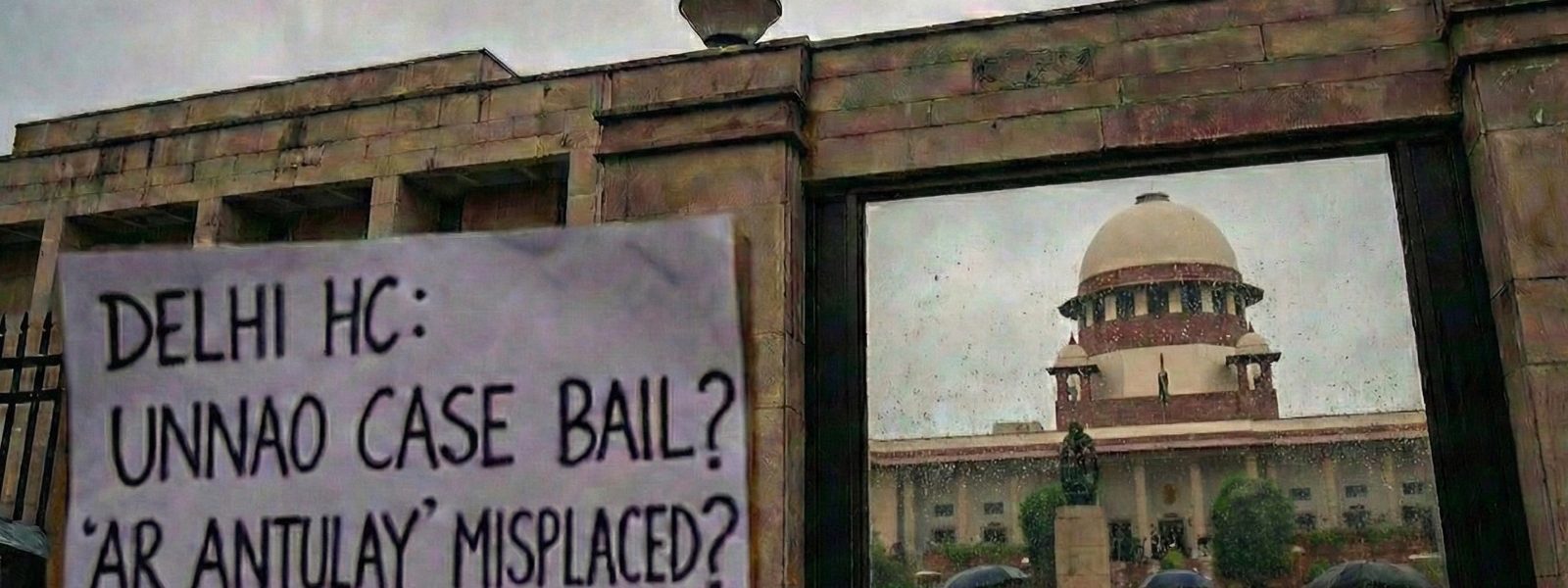

The High Court’s approach, with respect, overlooks a first principle of stare decisis. The authority binds for what it decides, not for what it merely resembles or by stretch of imagination finds relatable. A. R. Antulay was not a case about offences against children, nor about aggravated liability, nor about the interpretation of social legislation animated by a protective purpose. Its conclusion cannot be transplanted, intact and unquestioned, into a wholly different statutory terrain without asking whether such reliance advances, or instead frustrates, the mischief the later enactment was designed to remedy.

Yet the error is not without its redeeming possibility. The matter has now travelled to the Supreme Court. The occasion is thus presented for the Apex Court to lay to rest the lingering ghost of A. R. Antulay by drawing the distinction which the High Court declined to make and thereby restoring the doctrine to its proper bounds, and allow the law to speak in the voice of the statute before it.

Author: The author, Himanshu K. Mishra, is a penultimate-year student of law who reads for the B.Sc. LL.B. (Hons.)[Cyber Security] course at the National Law Institute University, Bhopal. His public law writings primarily engage with a re-examination of practices and policies relating to disability rights, human rights, legislative processes, and affirmative action.

[Ed Note: This piece was edited by Aditi and published by Vedang from the Student Editorial Team.]