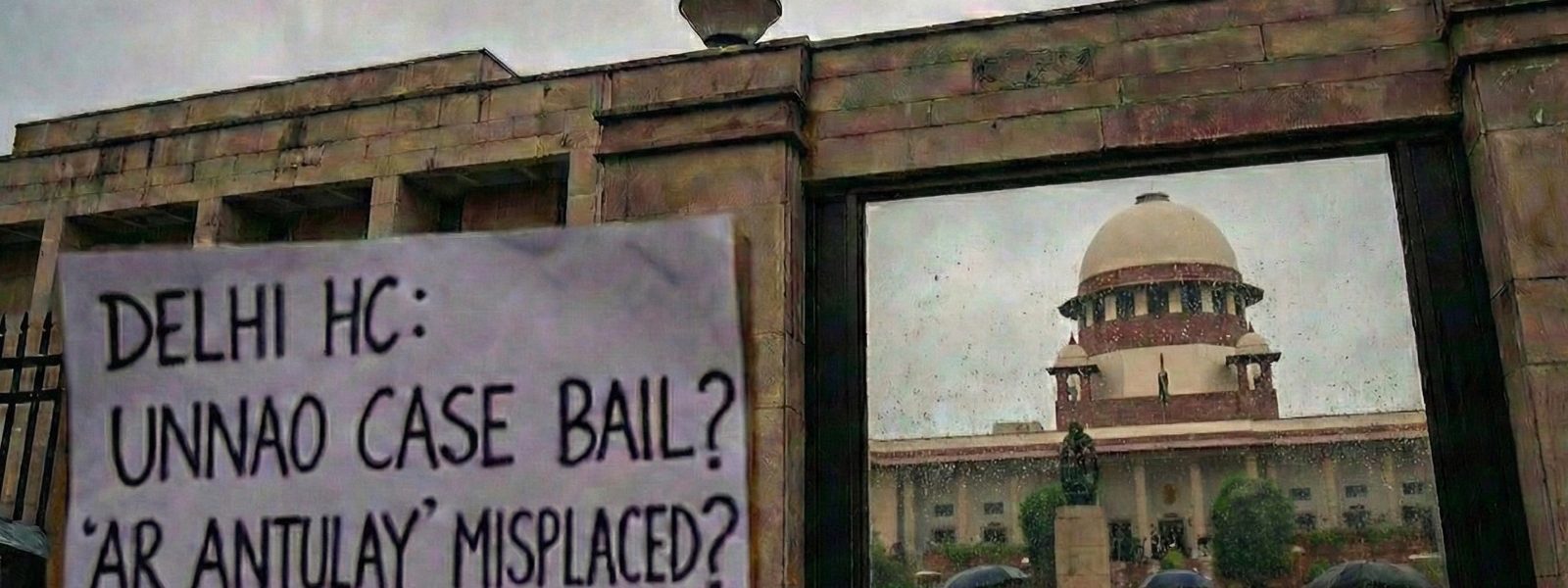

A disquiet attends the judgment of the Delhi High Court in Kuldeep Singh Sengar v. Central Bureau of Investigation, infamously known as the Unnao Rape case. Beneath a surface of doctrinal fidelity lies a question of whether the expression “public servant” in the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012, (“POCSO Act”) is capable of including within its ambit a sitting Member of the Legislative Assembly.

This Blog deals with the question in two parts. Part I adopts an internal point of view. Accepting, arguendo, A. R. Antulay v. R. S. Nayak as settled law for present purposes, it examines whether its ratio possesses the requisite fit to govern the interpretation of aggravated liability under the POCSO Act. Part II examines the interpretive methodology employed in A. R. Antulay and the reasoning by which that decision was reached. It evaluates whether the principle remains sound when tested against settled rules of statutory construction, referential legislation, and purposive interpretation.

The Context

The point arose in an appeal from a conviction made under the POCSO Act, 2012, where the offence was treated as aggravated on the footing that the accused, who was a sitting Member of the Legislative Assembly at the time of commission of the offence, was a “public servant” within the meaning of Section 5(c) of the Act.

The statute itself furnishes no definition. By force of Section 2(2) of the Act, a recourse, therefore, had to be made to the Indian Penal Code, and in particular to Section 21. The trial court, relying on L.K. Advani, sought to adopt an expansive view, resting upon the public character of the office held. The Appellant contended, however, that the field was already occupied by authority, and that A. R. Antulay v. R. S. Nayak admits of no such enlargement. The Court held that a sitting Member of the Legislature does not fall within the expression “public servant” for the purposes of Section 5(c) of the POCSO Act, for the reason that the statute, by express incorporation, confines the definition to Section 21 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (“IPC”), and that provision, as authoritatively construed by the Supreme Court in A. R. Antulay v. R. S. Nayak, admits of no wider construction.

The High Court’s approach at the first appearance appears faithful to precedent, but a deeper introspection reveals that it is arguably inattentive to statutory purpose and primary rules of construction.

Statutory Architecture of Important Definitions

The starting point of the inquiry must be the interpretive mechanism embedded within the POCSO Act itself. The Act does not define the term “public servant” independently. Instead, it permits reliance on definitions contained in three different enactments. Namely, the IPC, the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (“CrPC”), and the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (“JJ Act”).

Neither the CrPC nor the JJ Act supplies a definition of the expression “public servant”. The statute, therefore, directs attention to Section 21 of the IPC, where the term is defined in precise and enumerated form. On its face, this is an exercise in ordinary statutory cross-referencing. The difficulty, however, lies not in the language of Section 21 itself, but in the manner in which it has been judicially construed. The provision has long been treated as exhaustive and, in criminal law, as admitting of strict construction. It was upon this understanding, and the authority of A. R. Antulay, that the High Court held that a sitting Member of the Legislature does not fall within the expression “public servant” for the purposes of the POCSO Act.

Why the High Court’s Conclusion is Unsustainable

Assuming, for the sake of argument, that A. R. Antulay was correctly decided, its application in the present context is nevertheless misplaced, for it was rendered within a distinct statutory setting and for a limited purpose which the present case does not share.

Firstly, Antulay’s ratio arose under the Prevention of Corruption Act (“PC Act”) of 1947. The purpose of Section 2(c) read with Section 19 of the PC Act 1947 was procedural restraint and safeguard, particularly the protection of public officials from vexatious and politically motivated prosecutions through the mechanism of prior sanction. The Supreme Court’s interpretive move was thus driven by a concern to shield the office from abuse of criminal process and not to enlarge criminal liability.

The POCSO Act, by contrast, is a protective, victim-centric social legislation, enacted to address structural power imbalances and endemic under-reporting of sexual offences against children. The question under POCSO is not one of procedural immunity, but of aggravation based on abuse of authority. To transpose an interpretation forged in the restrictive logic of corruption law into the expansive moral universe of child protection law is to ignore the settled principle that statutory meaning is to be conditioned by statutory purpose.

Secondly, a close reading of Antulay reveals that its ratio was expressly confined to whether an MLA could be treated as a public servant for the purposes of attracting the sanction requirement under Section 6 of the PC Act 1947. The Court’s reasoning repeatedly emphasised that sanction provisions must be construed strictly because they operate as jurisdictional bars. The Delhi High Court, on the other hand, wrongly treated Antulay as laying down a general and immutable proposition that all legislators are excluded from Section 21 IPC for all statutory purposes. This is a category error.

Thirdly, in Antulay, Section 21 IPC was construed defensively, so as not to widen the class of persons entitled to sanction protection beyond what Parliament had clearly provided. The Court adopted a narrow reading because expansion would have the effect of insulating political actors from prosecution, contrary to legislative intent. Under POCSO, however, the invocation of Section 21 IPC serves a diametrically opposite function. It determines whether a person who wields public authority should be subject to greater penal consequences when that authority is abused.

Fourthly, Antulay proceeded on a formalistic distinction between “office” and “seat”. It emphasises that an MLA is not in the service or pay of the Government. This distinction made sense in the context of executive accountability and sanctioning authority. POCSO, however, is concerned not with the source of remuneration but with positional dominance and coercive capacity. A sitting Member of Parliament or State Assembly exercises constitutionally recognised influence, commands access to state machinery, and enjoys institutional power capable of silencing victims. To insist upon the executive-service test in this context is to privilege form over function, contrary to the logic of aggravation provisions.

Fifthly, the Court has completely ignored (or failed to deal with) a material legislative distinction created by Section 42A of the POCSO Act, inserted by way of Amendment in 2013, which expressly declares that the provisions of the Act are in addition to, and not in derogation of, any other law, and that in the event of inconsistency, POCSO shall prevail. No parallel overriding provision existed in the PC, 1947, which formed the statutory backdrop of Antulay.

Further, Antulay construed Section 2 of the PC Act, 1947, which defined “public servant” for the purposes of that Act by reference to Section 21 of the IPC, supplemented by specific inclusions of employees of corporations, local authorities, and statutory bodies. The definition was thus referentially limited and framed within a closed statutory universe tethering to the immediate concerns of the 1947 Act.

Significantly, Parliament revisited this very question in the PC Act, 1988. Departing from the earlier formulation, it expressly expanded the definition to include “any person who holds an office by virtue of which he is authorised or required to perform any public duty.” This legislative move is not incidental. It constitutes a clear parliamentary response to the narrow construction adopted under the 1947 regime, signalling an intention to shift the focus from formal employment to functional authority.

The contrast becomes even sharper when one turns to the POCSO Act. Unlike Section 2 of the PC Act, 1947 which opened with the confined phrase “for the purposes of this Act”, Section 2 of POCSO begins with the materially different formulation, “unless the context otherwise requires”. The latter is a classic contextual qualifier. It invites and indeed requires the interpreter to read definitions flexibly, in light of statutory purpose and setting.

To read both formulations as doing the same interpretive work is to collapse two distinct legislative techniques into one. Antulay proceeded within a statute that fixed meaning inwardly on the other hand POCSO operates within a statute that expressly subordinates definition to context which is a fairly outward approach. The High Court’s reliance on Antulay therefore overlooks not merely a difference in subject-matter, but a fundamental divergence in legislative instruction as to how meaning is to be ascertained.

For these reasons, even on the assumption that A. R. Antulay was correctly decided, its application in the present context cannot be sustained. The difficulty, however, does not end with misapplication. It invites a further inquiry into whether the interpretive foundations of Antulay itself are capable of bearing the weight that has since been placed upon them.

Author: The author, Himanshu K. Mishra, is a penultimate-year student of law who reads for the B.Sc. LL.B. (Hons.)[Cyber Security] course at the National Law Institute University, Bhopal. His public law writings primarily engage with a re-examination of practices and policies relating to disability rights, human rights, legislative processes, and affirmative action.

[Ed Note: This piece was edited by Aditi and published by Vedang from the Student Editorial Team.]