Summary: In the concluding arguments from the petitioner’s side on Days 8 and 9 of the hearings, the Court witnesses intense discussion on internal sovereignty, the impugned Reorganisation Act, Article 370 as a founding constitutional moments as well as looked to jurisprudence in Pakistan with regard to actions taking away federal power.

On Day 8, Senior Advocate Dinesh Dwivedi extended the line of arguments offered by Senior Advocates Kapil Sibal and Dushyant Dave. He explained the exceptionality of Kashmir compared to other states, the primary being the fact that a standstill agreement was not signed between the Union of India and Kashmir. The exclusion of the applicability of Article 238 by Article 370 is a testimony of the range of autonomy that Kashmir had. Kashmir ceded at a different time as an independent nation and did not merge with the Union of India. Dwivedi also talked about ‘internal sovereignty’ being maintained by the ruler of Kashmir, similar to arguments that Dr. Rajeev Dhavan raised on Day 6 of the hearings.

However, upon being asked by the CJI whether the Union of India lost its power to apply the provisions of the Indian Constitution to J&K after the dissolution of the J&K Constituent Assembly in 1957, Dwivedi said that the illegality of actions on the part of the Union of India in passing the Constitutional Orders after 1957 did not justify the validity of such actions, referring to the orders passed between 1957-2018. When a similar question was posed to Dushyant Dave earlier on Day 7 of the hearings, Dave insisted that the application of the orders after 1957 had attained the form of practice and did not talk about the legitimacy of such orders. Dwivedi argued that constitutions cannot be understood as an interim measure. They are made for a nation’s life and not for a day.

The Reorganisation Act

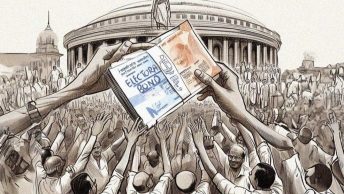

Senior Advocate CA Singh argued about the legitimacy of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act, 2019. He explained the illegality concerning the passing of the bill. The eighteenth amendment to the Constitution of India expands the definition of the “state” to include Union Territories (“UTs”) and lays down that clause (a) of Article 3 consists of the power to form a new State or UT by uniting a part of a State or UT to another State or UT, did not apply to J&K on August 5, 2019. Upon being asked by the CJI if the conversion of the State into UT and abrogation of Article 370 were severable, Singh affirmed that these were two different issues. Singh submitted that if the state’s reorganization was still possible, it could only be done under Article 368 and was outside the purview of Article 3. Singh also said that the action was a warning for the whole country as a party in the center, which also holds power in a state, can convert a state by a simple majority.

CA Singh took the Bench through the history of Articles 3 and 4, as emanating from the Government of India Act, 1919, and the Government of India Act, 1935. The intent was always to increase democratic participation and self-representation, not retrogression. He also built upon the argument of Senior Advocate Naphade as regards the loss of representation for Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh because of the actions of the Government in 2019. A simple majority and the application of Article 3 wipe out all constitutional rights.

On Political Sovereignty

Senior Advocate Sanjay Parikh talked about the J&K Constitution, laying down an economic plan for the state. The sovereignty that rested with the people was translated into a manifesto or constitution as it became an expression of sovereignty. A written constitution anywhere is a statement of the supremacy of that constitution. Referring to Justice AS Anand’s book Constitution Of Jammu & Kashmir – Its Development & Comments, Parikh said that autonomy and sovereignty are interchangeable, and the idea of having autonomy also meant that sovereignty rested with the people of Kashmir. The conclusion of the Constituent Assembly means the absence of concurrence. Elaborating on the maxim “what cannot be done directly cannot also be done indirectly,” Parikh submitted that the ‘recommendation of the Constituent Assembly’ was replaced by the ‘recommendation of Parliament.’ This explanation was changed without the prior recommendation of the Constituent Assembly.

Senior Advocate SC Pen took the Bench through the history of the region. He said the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir had a choice to be a part of Pakistan or India. The constitutional commitment should be interpreted strongly as an area chose to be a minority in the backdrop of partition. Being an anti-majoritarian constitution, the Indian Constitution provides for asymmetric federalism and protection against majoritarianism.

On Day 9, Senior Advocate Nitya Ramakrishnan debunked the temporary provision myth. She contested the reasoning of “greater integration” being fallacious. She said integration is not a function of central control or power, as there was a democratic sense of shared sovereignty between the two entities. As opposed to the idea of internal sovereignty, which other petitioners raised, Ramakrishnan raised the argument of “political sovereignty” vesting with the people of J&K. The people of J&K were political sovereigns. It was Article 370 that recognized this idea of shared sovereignty of the people of Kashmir. This shared sovereignty was a system of checks and balances reflecting the power of the center and the state of J&K.

Article 370, representing the will of the people of J&K, does not recognize a Governor not advised by the council of ministers. Constitutional Orders issued during the President’s rule, therefore, become incompetent. Article 356, being subservient to Article 370, cannot take the power of a responsible state government. Such a will, she said, has to come from the Constituent Assembly of J&K directly, and even a responsible government cannot suffice it. An agency equal to the mandate and stature of the Constituent Assembly alone can recommend the abrogation of Article 370. After 1957, no agency could be equal to the Constituent Assembly of J&K. Nitya Ramakrishnan concluded her arguments by saying that “even if Jammu and Kashmir flows with honey and milk, the argument that their rights have to be destroyed for that will not be counted”.

Founding Moments

Senior Advocate Menaka Guruswamy referred to the question posed to Senior Advocate Dwivedi as regards the importance of the statements made in the Constituent Assembly. She argued that in the case of Kashmir, there were two constituent bodies, and the question it posed was whether the Constitution could be altered in opposition to the views of the founders. She talked about the “founding moments” of constitutions being seminal in the context of the transformative and expansive interpretive jurisprudence of the Supreme Court of India. Article 370 was a founding intention as the motive was to recognize the state and bring diversity and regional representation in the form of togetherness to the three regions – Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh.

Advocate Manish Tiwari said that as India was building a republic, it was necessary to manage the peripheries through constitutional guarantees. He mentioned the special provisions extending to the North-East. SG Tushar Mehta responded, saying there was a difference between temporary provisions extending to J&K and special provisions extending to the North-East.

Looking to Neighbouring Jurisprudence

Senior Advocate Gopal Sankarnarayanan mentioned the Gilgit Baltistan Order 2018 (replacing the GB Empowerment and Self-Governance Order of 2009), promulgated by the Government of Pakistan to primarily bring the extraction of minerals and hydropower under its control, give the people of Pakistan the rights of citizenship and take away self-governance from these regions. The Government had, however, promised more political powers to the territory. The action of the Government of Pakistan was struck down by the Gilgit-Baltistan Supreme Appellate Court but was endorsed by the Supreme Court of Pakistan. (To get a broader understanding of the 2018 GB Order, readers are directed to I.A. Rehman’s essay here).

It is noted by the author for the information of the readers that Gilgit-Baltistan and Pakistan-administered Jammu and Kashmir are parts of the erstwhile State of J&K. As of now, the State of J&K is divided between three countries.

The CJI questioned that while the Constitution of J&K establishes a relationship with the Union of India, how can this relationship effectively bind the Indian Dominion, Parliament, and the executive unless it finds embodiment within the Indian Constitution. Sankarnarayanan said that the Indian Constitution recognizes a Constituent Assembly for only one state, which also had the power to abrogate the clause, and this task of the Assembly was recognized by the Constitution of India.

The petitioners concluded their arguments on Day 9 of the hearings.

Aurif Muzafar is a doctoral fellow at NALSAR. He is also a Research Associate for the MK Nambyar SAARC Law Center, NALSAR.

[Ed note: This article was edited by Archita Satish and posted by Harshitha Adari from our Student Editorial Team]

Great read! Simple and effective I appreciate your Content .Thanks for the valuable insights!”