In this piece, we continue the discussion on Dr Datar’s paper, the summary of which can be accessed here. In this response, Jeffrey A. Redding critically engages with Darshan Datar’s paper on the Indian Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on religion, situating his work within recent scholarship surrounding religion and secularism.

During the several years that we overlapped in Melbourne, it was always a pleasure to intellectually converse with Dr. Darshan Datar over casual get-togethers. I am thus grateful to the editors of Law and Other Things for this opportunity to more formally engage with Darshan’s recent scholarly work, albeit from a much greater geographical distance. In this post, I will not spend much time summarizing Darshan’s article as he has already provided an extensive overview of it in an earlier post in this series. What I want to do here instead is briefly interpellate Darshan’s current article into a body of critical scholarship on religion and secularism to raise some questions and directions for Darshan’s future work on comparative law and religion.

By way of introduction, Darshan’s article allows us to readily witness the mobile and protean quality of the category of ‘religion’ especially in its legal dimensions. Examining Indian constitutional cases concerning freedom of religion and other cases concerning what Darshan configures as the non-establishment of religion, Darshan demonstrates that there is no single conception of religion dominating Indian constitutional practice. Further, within the line of cases examined in the article concerning non-establishment, Darshan demonstrates that there are different areas of state practice that are either more, or less governed by Indian non-establishment norms (and anxieties): “The Constitution [of India] separates religion from core governmental functions such as education, taxation, elections, and public funds. Considering this, it is clear that the text of the Indian Constitution has a non-establishment principle in certain enumerated fields” (373, emphasis added). Fundamentally, Datar traces the diverse lives of the category ‘religion’ in different times and contexts while also highlighting some of the political and social stakes of all this variegation.

In doing this kind of work, Darshan methodologically aligns himself with a line of critical anthropological thought concerning the category and conceptualization of ‘religion.’ An evidently crucial scholar in this space has been Talal Asad who made the following observations more than 30 years ago:

“Religious symbols—whether one thinks of them in terms of communication or of cognition, of guiding action or of expressing emotion—cannot be understood independently of their historical relations with nonreligious symbols or of their articulations in and of social life, in which work and power are always crucial. My argument, I must stress, is not just that religious symbols are intimately linked to social life (and so change with it), or that they usually support dominant political power (and occasionally oppose it). It is that different kinds of practice and discourse are intrinsic to the field in which religious representations (like any representation) acquire their identity and their truthfulness. From this it does not follow that the meanings of religious practices and utterances are to be sought in social phenomena, but only that their possibility and their authoritative status are to be explained as products of historically distinctive disciplines and forces (Asad 1993: 53–54).”

Asad then goes on to stress the importance of analyses of religion which disaggregate: “The anthropological student of particular religions should therefore begin from this point, in a sense unpacking the comprehensive concept which he or she translates as ‘religion’ into heterogeneous elements” (Ibid.: 54).

Overwhelmingly, I read Darshan’s article to be doing this kind of important disaggregating work. If that is the case though, there are some dissonant moments in the article worth highlighting too. Notably, when Darshan moves between his discussions of freedom of religion and non-establishment jurisprudence, the concept of ‘secularism’ only emerges seriously in relation to the latter discussion. Indeed, in the latter half of his article, Darshan moves seamlessly and in an aggregating and conceptually collapsing manner between discussions of ‘separation of church and state’ and ‘non-establishment’ and ‘secularism,’ writing:

“Non-establishment is a specific form of the separation of church and state which ensures that government cannot establish a state church or endorse, through explicit or implicit policy, the doctrines of a specific religion. Judicial accounts of the concept of secularism in India are contested. The Supreme Court . . . has referenced a series of related concepts to explain the meaning of secularism (367).”

Later, Darshan also observes: “The Indian Constitution did not originally reference non-establishment, secularism, separation of church and state, or laicite” (369).

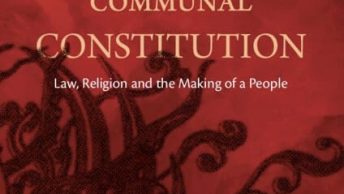

In highlighting this collating aspect of Darshan’s article, the point is not to claim that these various ideas and concepts should be properly viewed as individually distinct rather than intimately related to each other. The mutual connections between these ideas and concepts are posited in a great deal of traditional constitutional law scholarship and I do not mean to repudiate that scholarship. But there seems to be a further point that could be made here by Darshan that would more deeply situate his work within critical work on religion and secularism like that highlighted above. Indeed, Darshan’s observation of the expanding and contracting nature of the ‘religion’ category in Indian constitutional jurisprudence—what Julia Stephens might characterize as its “rubber-band” like qualities (Stephens 2018: 10–15)—is fundamentally in conversation with Talal Asad’s previous work.

Other authors important here include Hussein Ali Agrama whose 2012 monograph Questioning Secularism: Islam, Sovereignty, and the Rule of Law in Modern Egypt argues that perhaps the most interesting aspect of secularism is not its (sometimes) efforts to separate state and church (or law and religion) but, rather, the ways secularism tends to provoke and agitate crises concerning previous détentes between these competing spheres of governance.

Darshan’s work can also be read to be in conversation with a key framework provided by my 2020 monograph A Secular Need: Islamic Law and State Governance in Contemporary India. In this monograph, I emphasize that there are both loving and hateful aspects of Indian secularism and that these simultaneous affects are evidence of Indian secularism’s dependency on and need for religious minorities like Muslims along with their non-state institutions and practices. With this in mind, one way to read the two different major parts of Darshan’s article is to understand the first part as telling a story of Indian secularism’s absorptive love of India’s religious minorities (including Muslims) through the judicial running together of Hindu religiosity with Hindu cultural practices including an allegedly secular and assimilative outlook on life. By way of contrast, the second half of the article and its story of the inculturation of Hinduism can be read simultaneously as a practical illustration of how Indian minorities—and especially Indian Muslims—are radically otherized by secular hate.

Secularism’s hateful aspects are not emphasized by many scholars. Indeed, many scholars are evidently uncomfortable discussing these aspects of secularism preferring instead to characterize the invocation and deployment of secularism by Hindu nationalists, for example, as duplicitous or even fraudulent. In mentioning fraud here, I want to highlight how conceptions of religious fraud circulate through Darshan’s article and the caution that I feel needs to be present on this slippery terrain. For example, in the introduction to Darshan’s article, when discussing the possibility of under- or overinclusive definitions of religion, Darshan observes that “overinclusive definitions of religion [can] result in people committing fraud against the government by claiming to be religious and garnering the benefits of being religious without being religious” (353–54). This conception of religious fraud seems also operative (if much more covertly) in Darshan’s animating thesis in his article, namely that “Indian judges have a broad concept of religion in free exercise cases [but] judges narrow their concept of religion in cases which implicate the separation of Church and State” (354). Darshan goes on to characterize the latter move as belonging to a set of wily “definitional strategies used by judges” (354).

By way of contrast, there is a different perspective on the (im)possibility of religious fraud provided by law and society scholarship regarding religion and other adjacent phenomenon. Emphasizing the importance of taking the words and concepts used by ordinary people seriously, the legal historian and well-known law and society scholar Lawrence Friedman has written of how

“[t]he law and society movement relates to the legal system more or less the way the sociology of religion relates to religious life. Sociologists of religion study religion as a social phenomenon. It is no part of their business to decide whether this religion, or this dogma or belief, is true or false, moral or immoral. Religions are systems of beliefs and behaviors that rest on tradition, emotions, moral postulates. They can also be studied as aspects of life in society. The same is true of legal systems. They can be studied as social phenomena, without passing comment on their normative content (Friedman 1986: 765).”

Clearly, Darshan’s article is both in conversation and tension with this articulation of how to methodologically approach the concept of religion by an early and influential scholar in the US law and society movement. Emphasizing a close listening to the various ways the Indian constitution speaks religion, but also conveying a concern with too easy invocations of it, Darshan’s article crucially impresses upon his readers the non-evident and counterintuitive ways religion emerges in constitutional practice whether in India or elsewhere.

References

Agrama, Hussein Ali. Questioning Secularism: Islam, Sovereignty, and the Rule of Law in Modern Egypt. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Asad, Talal. Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Friedman, Lawrence M. “The Law and Society Movement.” Stanford Law Review 38, no. 3 (1986): 763–80.

Redding, Jeffrey A. A Secular Need: Islamic Law and State Governance in Contemporary India. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2020.

Stephens, Julia. Governing Islam: Law, Empire, and Secularism in South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Jeffrey A. Redding teaches Social Equality Law at NOVA School of Law in Lisbon where he is also the Equality Law Coordinator of the NOVA Center for the Study of Gender, Family, and the Law.

Editorial Note: This piece was edited by Saranya Ravindran and Thejalakshmi Anil. It was published by Abhishek Sanjay.