The Indian Feminist Judgments project [IFJP] is a collaboration between feminist legal academics, litigators and judges, practitioners, activists from law and other disciplines, who are using a feminist lens to re-write alternative opinions to existing judgements. Indian Law Review, Volume 5 (Issue 3) presents a set of six re-written judgements and accompanying commentaries that were prepared as part of the IFJP.

This interview with Sannoy Das and Ananyaa Mazumdar was conducted over a Zoom call and edited for length and clarity. Sannoy is a SJD candidate at Harvard Law School and an Assistant Professor at Jindal Global Law School. Ananyaa is a practicing lawyer at the Supreme Court, New Delhi. This interview pertains to their rewriting of the Charan Lal Sahu judgement regarding constitutionality of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy Compensation scheme.

[Ed Note: You can find information with regards to the podcast and can access all the episodes by clicking here]

Shravani: Hello, everyone. My name is Shravani Shendye and I am a Legal Editor with the LAOT blog. Sannoy and Ananya are joining us for a brief interview on their work with the Indian Feminists Judgment Project. The judgment that we are reviewing today is the Charan Lal Sahu case. The authors present a dissenting opinion from the lens of the feminist judge to the Supreme Court’s decision that followed in the wake of the Bhopal Gas Leak Tragedy. They primarily find that the law empowering the State to supplant the victim-survivors as plaintiffs was unconstitutional.

The industrial disaster occurred in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh on the intervening night between 2 and 3 December of 1984. The highly toxic Methyl Isocyanate (“MIC”) leaked out from Union Carbide India Ltd. (UCIL)’s plants and resulted in thousands of deaths from immediate exposure; medium to long-term health conditions among survivors; livestock damage; and long-term congenital medical issues afflicting thousands of occupants, residents and future generations. The Court in the Charan Lal Sahu case had upheld the constitutional validity of the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act, 1985. In February 1989, it ordered UCIL/UCC to pay a settlement of 470 million, what the authors refer to as paltry sum. The Court also approved in sweeping terms, the power of the government to extinguish and settle claims that numerous individuals had against UCIL and UCC. Therefore, the state’s move to divest its citizenry of its right to pursue claims against a tortfeasor, and settle all claims at an unconscionably low amount was validated by the Court.

Charan Lal Sahu was a Supreme Court Advocate on Record, who filed this case, amongst others, who joined him, some of whom were representatives of the people who were affected by the gas leak. He was also amongst the many individuals who were fighting for proper compensation for the victims of the case.

Shravani: You mention that your dissenting opinion demonstrates the limitations implicit in the feminist judgement endeavour. Could you briefly explain the idea of feminist judging and the limitations that constrained you during this exercise?

Ananya: Our aim was to not only recast the judgment that we are dealing with, but also to try and engage with this question of what the judgment writing process entails. We thought this particular judgment is a good example of what that might look like, because it exposes a lot of flaws that exist in everyday legal reasoning, in ways that we grapple with questions in feminism as well. So, for instance, the limitations in the feminist judgment writing process, itself has the limitations of the particular institution being studied. All institutions replicate existing hierarchies and power dynamics that exist in society and the judiciary becomes a microcosm where you’re just replicating the same power dynamic when you’re undertaking something like a feminist rewriting project, you’re still, to some extent, constrained by the limitations imposed by that structure; you’re still constrained by the limitations imposed by them, having to pander to what the institutional norms are, because you’re writing as a judge, at the end of the day, a judge is very much a part of the institution that is the state, that is the judiciary. This brings with it its own contradictions. And it brings with it certain goals that a feminist person would not prioritize, but a feminist judge necessarily has to, and there is tension in being a feminist and being a judge.

Sannoy: The Indian feminist judgment project is not the only feminist judgment project; it comes on the back of others in which this question has been raised and answered. The way you participate in the feminist judgment project is to say that feminist judge is better than a non-feminist judge. No feminist would suggest that, that judgment writing and being the judge is necessarily the right way of getting to what one’s political projects might be. The ability for a feminist judge to decide, might simply be the single most important thing for some feminists, or for some goals of a feminist movement but not all, and certainly if one considers feminism as an umbrella term for a large number of political projects, then those political projects have clashes between them. And if you sympathize with some of those clashes, you will find that, that the court or a judge is not your vessel or vehicle of emancipation, or a way to carry out emancipatory politics in a larger sense. Those limitations are just written into a feminist judgment project, the moment you sign up, you sign up to those limitations. But I think it’s still valuable because you think that it’s better than being a non-feminist judge.

Ananyaa: The carceral logic implicit in a lot of projects on judgment rewriting, is not something that subsections, within the larger feminist movement would ever find themselves aligning with, and you have to reconcile that that’s not something you’re going to be able to get past in judgment rewriting project.

Shravani: Were there any competing alternatives within the framework of feminism from which the judgement could have been re-written, especially in terms of intersectionality?

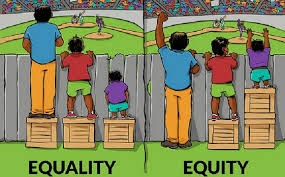

Sannoy: In certain ways, working with legal categories requires you to have good definitions of categories. Having good definitions of categories is the hallmark of modern liberalism. There are ways in which feminists aligned with a broader liberal idea of adjudication and legality would find it compelling that we can delineate categories, especially categories such as freedom, individual rights, claims against the state etc. and have good doctrinal tests to deal with those. But at least in some circles that Ananyaa and I inhibit, that’s not necessarily the way in which the feminist conversation takes place and thus it can seem a bit dated, because it doesn’t contain with it that critical edge that post-colonial or socialist thinking might associate with the feminist project. Socialist feminisms or post-colonial feminisms wouldn’t find that method appealing. So the way that we do this in the in the judgment is to say that that there is sincerely good critique that’s available to our methods, if we think in these ways, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that those are particularly helpful tools of judgment, especially because judgments are not only decisions, they are also decisions of general value, which means that they have doctrinal value, you should be able to abstract from a judgment to a principle so that the principle in the future can also be applied to a large number of cases. Whether that’s a good normative position in the world or not, it’s not the point, I think most judges think that way. Even from my little own practice background, I will think that most lawyers think that way. Categorical thinking aligns itself with one kind of feminism and doesn’t align itself with another.

Intersectionality has its place in legal reasoning, it was born out of law schools in the United States. It is a way of thinking about anti-discrimination law. But it is not particularly helpful way of thinking about state power. It might be but it doesn’t appear to me naturally to be the case, that the intersecting axes of marginalization is a good way to conceive of the power of the state vis-à-vis citizenry. In that sense, I think that framework has a lot to offer for the study of discrimination and equality. But our thrust in this decision is not on the questions of discrimination and equality. It’s a much more fundamental, political, theoretical question, what is the power of the state vis-à-vis citizenry? We know that power is constitutionally constrained but the question is, what aspects of constitutional reasoning can be modified using a feminist lens and which aspects of constitutional reasoning appear patriarchal? On that question, there is criticism available from the socialist strain, as well as from the post-colonial strain. And we deal with it, and we don’t think it’s appropriate for our purposes over here.

Ananyaa: I think I agree with him 100%, in terms of just trying to adopt intersectionality as a theoretical framework, I don’t think it wouldn’t work for a piece like this. More so because when you’re writing a judgement like this, there is some amount of integrity that you to bring to the process. I think it would compromise on that integrity, or that you could compromise on the authenticity of trying to recast the narrative, if we are trying to force some framework that might not organically otherwise apply. It would be slightly dishonest, to try and stretch things just to fit into a theoretical mould that would otherwise not necessarily advance the cause.

Shravani: I understood it as an intersectionality issue, because not everyone was affected equally by the disaster. I was trying to understand whether the feminist judge might have taken that into consideration. I understand that you are looking at the larger political question of the state the state had when it supplanted the actual victims, and how that works out.

Shravani: Sannoy, how has your research in the area of international trade law, international relations and political economy informed your writing for this project?

Sannoy: I started writing before I started doing my SJD on international trade law and international relations. During my teaching at Jindal Global Law School, I committed to participating in this. My partner suggested that somebody should write this and write it because it doesn’t directly deal with a women’s issue, it does not belong to the things that are clubbed as women’s issues like violence or discrimination. It had a degree of broad ranging interests on the theoretical side that I was interested in. International relations and political economy are about the same thing – about powers of corporations and powers of states and powers of individuals and whatever my theoretical understanding of that is, shows very little in this judgment. So, nobody, hopefully will judge me for my simple mindedness in writing this article.

Some of my broader interests play into the questions of state, the economy and people, how this operates not just at the national but a transnational scale, and this case is very important from the transnational point of view. Upendra Baxi wrote a lot of pieces to show how this was initially the promise of third world standing up to the power of global capital in one way, and then failing to stand up to the power of global capital in another way. This entire story is about that story. We kind of hinted that also in when we write about this judgment about the promises and the failures in that respect. It does tangentially tie into my other areas of research.

Shravani: Ananyaa, how has your background in economics as well as your experience as an advocate informed your writing for this project?

Ananyaa: When Professor Aparna Chandra was starting this project, I was just finishing law school. I’ve taken couple of months off before I started working. At that time, we needed research assistants, for a number of people who were taking on the rewriting project. I had initially started out assisting a couple of other professors. I finished that in about six months. When I was asked to do this judgment, I thought this case doesn’t intuitively seem like something that gives itself to a feminist retelling. At the time the first leg of this article was written which was the actual judgement part, I was barely a lawyer. I just started practicing. It was still exciting to me because I had just started out at the bar that time. I thought it was a venting exercise as well, trying to be able to do this, while you’re simultaneously working in the Supreme Court, on the side and being able to do something where you get to point out everything that’s problematic. I think that the point that really spoke to me was attacking not so much the judgment or the court, but assailing the logic on which a lot of the judgments writing in the Supreme Court is done. And it’s something that I took strong exception to, and a lot of instances, for instance, vocabulary that’s employed in judgment writing, a lot of reasoning processes that are employed, and being able to engage with that I thought was very exciting.

Shravani: In your article, you acknowledge how your dissent is not located in the same historical constraints as the Charan Lal Sahu decision. Even though the authors felt it was prudent not to avoid these in the paper itself, can you tell us now, how would a feminist judge might or might not have decided differently if we take into account the practical factors of that time that drove the Court to finding the Act as constitutional? Also, for the benefit of our listeners, it would be great if you could also briefly summarize these factors and state your reason for not applying these historical constraints to the process of rewriting.

Sannoy: The Supreme Court had already put its mark of approval on a settlement before Charan Lal Sahu was decided. It seemed like a strange exercise where you put your mark on settlement, saying the settlements is fair, $470 million, but is subject to the finding if the Act itself is constitutional in another judgment. But this is the same court, it’s seemed wild to me that maybe they will find it unconstitutional next day. It seemed like you would have to have an unbelievable degree of faith in people to say, one thing one day, and then completely revisit the question with an open mind that the next day, because they suddenly realize that all of this is unconstitutional. The question of historical constraint is this – there are institutional constraints that operate in the Supreme Court, you cannot just dissent easily, there are sensitive matters. Whether or not you can prove that as a social scientific fact is an interesting question. There’s a citation in our paper to a dissents’ piece that Krithika Ashok wrote in which she found that institutional constraints are very real. There are real reasons why judges don’t dissent on the bench even though they might want to disagree. These are still sort of hypotheses that academics can have. When one walks in a court and I having done some walking in the court in my life, I agree that it’s really hard to dissent.

The big constraint was that this was too big an issue, the matter had been settled, money was to be paid. If the court found this act to be unconstitutional, that entire settlement goes out of the door, and then when will the next settlement come and for how much amount? When will someone see a rupee is a real question? In this social matrix, whether somebody will have the luxury to intellectually pick this question apart that we have as academic writers of judgment 30 years later, is a real question. But if you cannot do that, then there is no point of writing this article, if you just simply acknowledge these constraints, then, I mean, by writing this dissent, we’re not changing the lives of anybody. We’re not bringing any closure to anyone, there is no justice being done in this process. But what is being done in a very loose sense, you’re appealing to the intelligence of a future day. Why do judges dissent in the first place? – Because you want to appeal to the intelligence of a future day.

Dissenting might have been practically impossible in 1989, but it is entirely possible today. As an academic exercise to see what, what’s wrong with our reasoning at a broader level, as the same kind of reasoning continues to filter down to our judgments even today, which is what Ananyaa was saying in the beginning, that there’s something exceptionally bad about the way that our Supreme Court, sometimes reasons. And this is yet another exercise in that project, and has nothing to really do with the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, which we can do nothing about. It would be incredibly foolish for us to think that this judgement is doing anything to that.

Ananyaa: Professor Das has already enumerated on the main practical constraints on the Bench at the time. The compensation was already decided, but the Supreme Court kept it subjective on the finding of the constitutionality of the very Act under which the compensation was being given. In terms of why we would want to set aside the practical constraints in the writing of our dissent, I can answer your second question a little more clearly now which was, how does my training in economics, for instance, inform my writing of this – I am able to see the value of a theoretical framework independent of whether it’s empirically verifiable or not. As Prof. Das eloquently articulated, there is still merit to trying to do something that’s right even if it is not workable, because at the end of the day, any social movement, anything that’s progressive is fundamentally born from our imagination, you have to in some ways to spend reality on some level, because when you look out the window, there are constraints and there is a time to be cognizant of it, there is a time to be cognizant of it as a practicing lawyer, something that I absolutely cannot discard any given point in time, and I must not. At the same time, we do it for the sake of appealing to a future that is ideal. The goal of scholarship is not to be tackled by the same thing that we would be tackled by if I was your judge then. You then owe it to everyone, to yourself as well, to try and do as honest a retelling as you can, as close to a feminist jurisprudence as you can take it. And that wouldn’t necessarily involve letting go of certain constraints that would have weighed in on the bench at the time.

Shravani: Why did you chose to not rewrite the majority opinion?

Sannoy: It was an aesthetic choice. It was a way of recognizing that it would not have been possible for the majority to write this decision at that point of time. Dissent gives you more freedom to write. Mimicking the court as much as possible and dissent is the place where you can go wild. It’s not common in India to see a lot of dissents.

Ananyaa: It allowed us a measure of engagement with the problematic logic of the judgement, in a way that perhaps rewriting the majority opinion would have. So, not only we get to recast the narrative in a certain way, we got to point out everything that was flawed. It was engaging as a format atleast.

[…] Posted byAnanyaa Mazumdar, Sannoy Das and Shravani Shendye […]

I learnt more information from this blog about the legal services.

JustAct is an Online Dispute Resolution platform offered by Lex Carta Private Limited and is set up by lawyers and professionals to disrupt the way disputes are resolved today.

A very thoughtful and needed blog, we need person who not only in theory but also practically raises this issues and work on them. For more information regarding laws made for women do visit LedX website and explore more.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!