Introduction

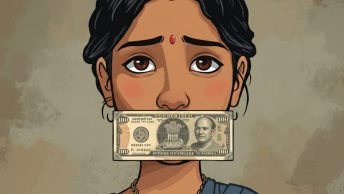

Amidst a recent global economic slowdown and lack of employment opportunities, employees have been subject to unrealistic work expectations and mounting distress. From enforcement of return-to-office mandates to calls for 90-hour work weeks, they are perceived merely as a capitalistic resource meant to be optimised. This perception is inconsistent with a dignitarian approach to the rights of the workers. Heightened expectations of round-the-clock availability, coupled with aggressive productivity, have resulted in a dilution of personal boundaries, as employers increasingly engage with employees beyond official working hours.

There is a growing demand for legislating the right to disconnect, that allows the employees to disengage from work outside official hours and curtails the encroachment of work-related communication in their personal lives. Several countries have already introduced the right to disconnect as part of broader efforts to extend legal protections for workers. France pioneered this legislative reform, and similar legislations have since been passed in countries across the globe, including developing countries such as Brazil and Argentina which have introduced variants of the right. Though the structures differ, they rest on the same underlying principle of preserving worker’s autonomy over their time and reinforcing the boundary between professional and personal life.

Its increasing global adoption has also intensified the discourse in India, with growing calls to recognise and institutionalise similar protections. However, critics claim that such a right could have unintended consequences in competitive business environments and question the need for such a protection when safeguards such as right to reasonable limitation on working hours exist. While delving into the socio-economic ramifications is not within its purview, this article makes a principled case arguing for the necessity of a distinct right to disconnect in light of the inadequacy of the existing safeguards. It also explores an ideal design for such a law, one that avoids an overtly paternalistic approach, and yet protects workers from the subtleties of workplace coercion. Lastly, it also assesses the suitability of introducing such a law within India’s current labour law regime.

Why the Right to Disconnect Matters

At its core, the right to disconnect may be perceived as an extension of the right to reasonable limitation of working hours. Article 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) states:

“Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay.”

This right is grounded in the principles of health, safety, and most importantly in human dignity. Being compelled to work incessantly, often out of economic necessity, at the cost of personal and social life, is demeaning to the self. This presents a two-fold issue: first, the circumvention by employers of the laws limiting work hours, or the absence of such laws altogether; and second, the expectation of round-the-clock availability of employees.

Laws capping working hours may define the temporal boundaries of labor, but they fail to tackle the more subtle encroachment of work into employees’ personal space outside official hours. The absence of clear regulations limiting after-hours communication means employers can manipulate the label of “work-related” communication to subtly demand continuous work availability. Even though laws limiting work-hour act as a critical safeguard against exploitation, a distinct and well-defined right to disconnect is necessary, to empower employees to effectively disengage from work without fear of reprisal, and to ensure that coexisting protections are not rendered redundant.

The Dilemma in Disconnecting

The complexity of the problem raises another important question, what does the right to disconnect really intend to protect: a workers’ interest or their choice? This distinction matters, because a law designed to safeguard workers’ interest will have stricter enforceability and deterrence and adopts a more paternalistic approach. The onus, in such an instance, would largely shift on the employer to not contact employees outside working hours, so as not to violate the law. Much like how the law legally obligates employers to provide maternity benefits to their employees, a right to disconnect would mandate them to refrain from initiating any work or related communication beyond official hours. But this deprives the employees of the choice to decide how much they want to work, even if they are willing to accept additional work in return for fair compensation.

By contrast, a choice-based approach places more autonomy in the hands of the worker. Similar to opting for overtime work, the employee retains the discretion to respond to employers beyond working hours, potentially in exchange for compensation. But this is precisely where the problem lies. The presumption of genuine autonomy in an employer-employee setup is illusory. If engaging with employers beyond work hours were to be optional for employees, the skewed power dynamics of their relationship would allow employers to easily coerce or pressure employees into such “voluntary” engagement. Worse, this creates a toxic link between work and pay, where employees feel compelled to overwork, unaware or dismissive of the long-term consequences for their well-being.

Both the interest and rights-based approach have inherent limitations. One strips the employee of autonomy over the quantum of work they wish to undertake; the other, in trying to preserve that autonomy, leaves room for subtle coercion by the employer. It is, therefore, unwise to fully endorse either model completely. Perhaps a balanced approach, such as permitting limited post-work availability on specific days or for a set number of hours, beyond which employer contact would be deemed unlawful, is the ideal solution.

A model law in pursuit of the right to disconnect should not be interpreted as an absolute abandonment of work-related duties, but rather as a calibrated intervention to protect workers from undue intrusion. Australia’s recent reform of the Fair Work Act provides a thoughtful example of how to balance the realities of modern work with employee welfare, while acknowledging the operational needs of industries that necessitate after-hours communication. The law introduces the concept of “(un)reasonable refusal” to communicate, allowing to contextually assess a refusal based on factors like the character of the contact, the degree of disruption, the employee’s role, personal circumstances, and any legal necessity of contact. Such assessments are sensitive to the individualised specifics of each case, and it encourages employers to adopt reasonable practices that uphold the right to disconnect without compromising critical operational functions.

Contextualizing Indian Laws

Formulating a right to disconnect within the Indian legal framework requires revisiting existing labour laws which, in their current form, fall short of offering the comprehensive work-life protections suited to the modern work landscape. This shortcoming can be traced to the absence of universally applicable laws regulating working hours. While certain statutes, such as the Factories Act, 1948 and the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, impose limits on the working hours of blue-collar workers, their applicability leaves out of its scope a large section of the country’s workforce.

A logical starting point would be to enact a law that reasonably limits working hours and which entails within its purview a broader segment of the economy’s workforce which includes white-collar employees. Presuming that such a regulation was to be enacted, the introduction of a complementary right to disconnect would ensure that the regulation attains its intended purpose. While the right to disconnect in India was earlier turned down as an alien concept when Supriya Sule introduced a private member bill, it does find relevancy within the country’s broader legal framework and interpretative context.

India, being a signatory to UDHR, is obligated to adopt its provisions, specifically Article 24 that seeks to protect the right to rest and leisure. Simultaneously, although it does not find explicit mention, the expansive interpretation of Article 21 which seeks to protect life and liberty can be argued to reasonably accommodate the right to disconnect. This is also supported by Articles 39(e) and 41, which mention the state’s responsibility to safeguard the health and strength of workers and to ensure just and humane working conditions.

As has been mentioned earlier, one of the fundamental reasons that call for the right to reasonable limitation of working hours is human dignity, an element the courts have held to be essential to life beyond mere existence. In Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India, dignity was interpreted to include the right to livelihood and fair pay. Similarly, Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan affirmed the State’s duty to ensure the comprehensive well-being of workers. Further, in Ramlila Maidan v. Home Secretary, the Court even recognised the right to sleep as intrinsic to the right to life, and its violation as an infringement of the right to privacy.

Building on these precedents: recognising rest, dignity, and privacy as core components of life, the right to disconnect emerges as a natural extension of the right to life. A worker’s time away from the workplace is vital not only for their physical and mental well-being, but also to preserve their autonomy and personal space. Just as the Supreme Court drew a boundary of one’s personal space by protecting sleep and privacy from undue interference, an employee ought to have, as a matter of right, the autonomy to disengage from work beyond reasonable hours without fear of reprisal.

Conclusion

Resistance to connectivity is not about the dismissal of technology, but the contestation of how technology, especially networked media, undercuts our lives, livelihoods, and sense of agency. Disconnection, in this context, aims to reassert some control and dignity in the wake of incessant work demands.

On these lines, the successful adoption of the right to disconnect, particularly in India, requires an overarching and context-sensitive policy that addresses the intricacies of a heterogenous workforce, economic realities in the country, and the existing competitive forces in the international market. An effective implementation of such a right demands more than a mere policy prescription, taking into account that a one-size-fits-all solution may be counterproductive. The legislature needs to implement these dynamics with sector-specific adjustments.

Bio: Shreyas Mishra is an undergraduate law student at the National University of Juridical Sciences (NUJS), Kolkata, with an interest in technology and policy and seeks to engage with contemporary legal developments through research and writing.

Ed Note: This piece was edited by Hamza Khan and published by Tamanna Yadav from the Student Editorial Team.