In the post-lunch session, the Supreme Court continued debating questions of constituent power, the difference between the nature of constituent assembly and legislative assembly, the permanence of Article 370, and the larger interpretation of the provision.

Whether ‘constituent assembly’ can be interpreted as ‘legislative assembly.

Reading Justice Jaganmohan Reddy’s judgment in the Kesavananda Bharati, Senior Advocate Mr. Kapil Sibal highlighted B.R. Ambedkar’s speech, where he stated that while the intent of a constituent assembly cannot be partisan, Parliament, if allowed to exercise constituent power, would act with partisan motives. Therefore, he argued that a legislative assembly cannot be converted into a constituent assembly. While the Constituent Assembly of India was not elected based on universal adult suffrage, Justice Kaul pointed out that the Constituent Assembly of the State of J&K was.

Justice Khanna then stated that there is a difference between Article 370, what was stated here, and what is the objective and purpose. Firstly, he said that Article 370 has an element of flexibility, whether based on consultation or prior acceptance. When the Constitution was adopted, J&K did not have its own Constitution or Constituent Assembly, but they were intended to come up. Therefore, if Article 370(3) was not to become defunct when the Constituent Assembly of J&K proposed the Constitution, Justice Khanna questioned why we cannot accept the argument that the Constituent Assembly under the proviso could also be interpreted to mean the legislative assembly, noting that the Parliament could alternatively have amended Article 370 also.

Replying to Justice Khanna’s statement that the aim was not to put Article 370 in a straightjacket, Mr. Sibal contended that the flexibility envisioned under Article 370(3) is at the instance of the Constituent Assembly, not the Parliament or the Legislature, as given under Article 147 of the J&K Constitution. Justice Khanna further pressed that since there was no Legislative Assembly of J&K at the time of the Constitution’s enactment, can we interpret the term Constituent Assembly to include Legislative Assembly? Mr. Sibal said there is no rule of interpretation supporting this since we can change any definition of any Constitution by this logic.

The first reference to the Constituent Assembly of J&K

The CJI then interjected to ask whether the first reference to the Constituent Assembly, before the Indian Constitution, is in the Maharaja’s proclamation. Mr. Sibal replied that it is in the Constituent Assembly debates. He further said that the Constitution makers always contemplated a Constituent Assembly for J&K, which came into existence in 1951.

When the Constituent Assembly dissolved, did Article 370 become permanent?

Summarising Mr. Sibal’s argument that a legislative assembly cannot exercise the functions of a constituent assembly, the CJI asked what happens if there is no Constituent Assembly. How would a proposal for abrogation by the President then be implemented in post-1957 India, when J&K’s Constituent Assembly ceased to exist? Mr. Sibal stressed the need to understand this in a historical context – the framers of the Constitution decided to use the term ‘constituent assembly’ with the agreement of the Maharaja.

The CJI followed up by asking what the envisaged constitutional process to abrogate or amend Article 370 was since the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly of J&K could not mean that there could be no proposal to modify Article 370. Upon further questioning, Mr. Sibal relented that there could be no such process since the Article was transient only till 1957, after which it became permanent.

Whether Article 370 is beyond amending powers?

Justice Kaul opined that the Constitution is a living document and enquired whether Article 370 is excluded from Parliament’s amending power, to which Mr. Sibal replied that he did not see using which constitutional powers they could amend the Article. Justice Kaul further clarified whether there is no mechanism at all to amend the Article, even if, say all of Kashmir wanted it. Mr. Sibal answered that a political act can do it. Posing more questions to Mr. Sibal’s argument, CJI Chandrachud asked whether Article 370 lies beyond Parliament’s power to amend under Article 368, to which Mr. Sibal replied in the affirmative. The CJI questioned whether we are creating a new category apart from the Basic Structure under which 370 falls, but Mr. Sibal said it is a pre-existing category.

The Application of the Constitution

Senior Advocate Gopal Sankaranarayanan advanced that even if clause 3 becomes inoperative, clause 1 can still be employed to make the entire Constitution applicable to J&K, with the consent of the Government of Kashmir. Justice Kaul clarified that, as per Mr. Sankaranarayanan, although Article 370 can be made ineffective, it cannot be removed from the Constitution. Mr. Sankaranarayanan laid down three categories under Article 370, wherein clause 2 is transitory, clause 3 provides for abrogation to be temporary – till the existence of the Constituent Assembly continued – clause 1 remained as the available option for correct assimilation. The CJI then asked Mr. Sibal to complete his argumentation before others stepped in.

Justice Gavai enquired if the Parliament can validly make all provisions of the Constitution applicable to J&K under Clause (1)(d). Mr. Sibal said the State could do it since the residuary power remained. The CJI again pressed why the Parliament cannot exercise its plenary amending power to abrogate Article 370. Unlike other princely states like Junagarh, Mr. Sibal responded that this is not a basic structure but a compact between two sovereigns embedded in our Constitution. When asked whether this sovereign compact could be overridden, Mr. Sibal said that that was a separate debate and the issue at hand was limited to the power and the process – whether the procedure followed by the government to abrogate Article 370 was in line with the authority given under it.

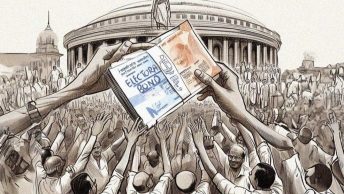

Justice Gavai posed the question of whether abrogation cannot be done unless the views of the entire population of J&K are considered. Mr. Sibal agreed. It is the partisan political measures that are carried through in legislation or otherwise which cannot be done. There should be fetters to what the parliament can do. The counsel relied on Ambedkar’s writings for this. The whole factual scenario of how the Bill was introduced at 11 pm, the Council of Ministers being suspended, and the Governor dissolving the Legislative Assembly has been reported from sentence to sentence in the Live Law live transcript. This is a purely political act; the Governor and Union Government have been acting in tandem to get rid of 370. Otherwise, why would any Governor do that?

The Power of Dissolution

Article 53 of the Constitution of J&K gives the Governor the power to dissolve the Assembly, which is not subject to the exception that the Governor must act on the aid of the Council of Ministers under Article 35. The process is as important as the substance when interpreting the Constitution. CJI Chandrachud wondered that while there are the optics as to how it was done, there is nothing about what was done. There is no challenge to what has been done. What is the power of Article 356? It is to restore democracy after a short period. You can’t amend the provisions of the Constitution under Article 356.

Article 3 of the Constitution was discussed thoroughly – the literal wording of the Article and its importance in light of the States Reorganization Act. Other than talking about whether consent or view is required. In other states, only views are required, whereas J&K consent is required to introduce the Bill – according to the 1954 Order. The Assembly was not in session, so the Governor became the Assembly, the Assembly became Parliament, and the Parliament gave consent on behalf of an Assembly that did not exist.

It then comes to severing the link between center and state altogether. You absorb the powers of the state with yourself as the executive, the parliament, and the legislature, and you decide without reference to any other institution, so you can do what you like. You give yourself consent and don’t seek consent from anyone else. The people who gave themselves this Constitution are left out of the process. This is a breakdown of the constitutional structure that was engrafted in the body, a complete breakdown. You do away with any representative form of government and make it irrepressible.

Avantika Kalra is a fourth-year student at NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad. She is interested in Constitutional law, public policy,and gender rights.

Gayatri Kondapalli is a third-year student at NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad.

[Ed Note: This post was edited by Aurif Muzafar who is a Kashmiri lawyer and writer and currently a doctoral student at NALSAR. It has been co-edited by Archita Satish and posted by Harshitha Adari from the Student Editorial Team]