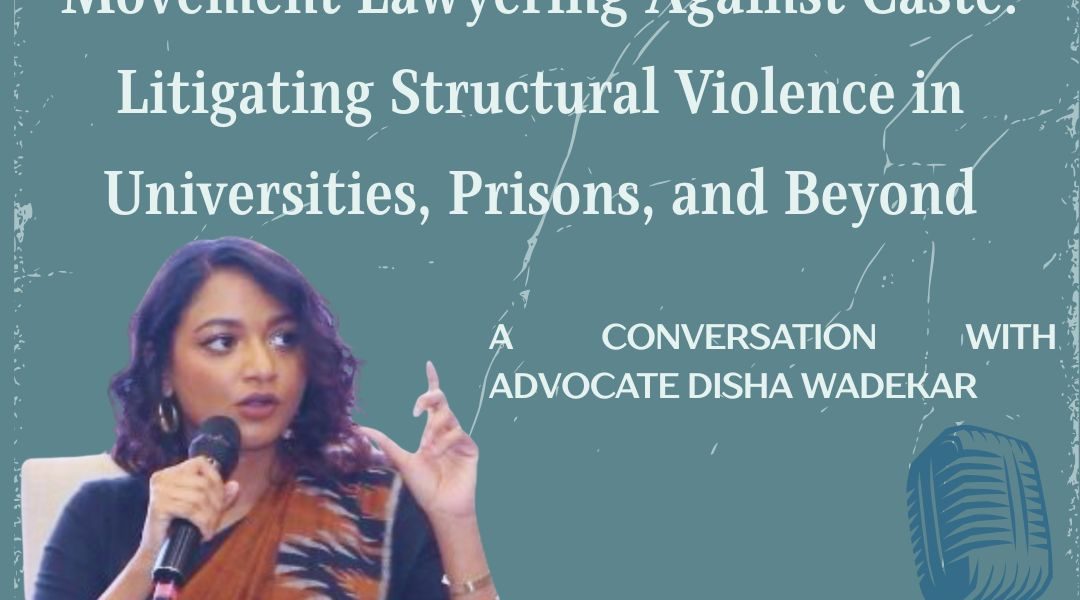

In this episode of the Law and Other Things podcast, host Sannidhi speaks with Advocate Disha Wadekar about the limits of India’s anti-discrimination law in addressing caste-based oppression in higher educational institutions and prisons. Drawing from her extensive work in landmark cases like those of Rohit Vemula, Dr. Payal Tadvi, and the prison manual litigation with journalist Sukanya Shantha, Disha outlines how systemic discrimination operates silently but violently through bureaucratic mechanisms and institutional apathy. She critiques India’s overemphasis on overt forms of discrimination and the lack of legal recognition for hostile academic environments. Advocating for “movement lawyering” over conventional public interest litigation, Disha calls for legal strategies rooted in lived realities and community engagement, arguing that transformative justice must be collective, not saviour-led. The conversation also explores how caste operates within state structures like prisons and how the illusion of “castelessness” helps normalize everyday forms of exclusion.

Sannidhi: In the corridors of India’s premier universities, where dreams are supposed to take flight, shadows gather instead. In colleges, where young minds should find refuge, fellowship letters are withdrawn like lifelines cut. In medical colleges, where healers are trained, the very air becomes poisoned with caste-based cruelty. And in the silence that follows, when Rohit writes his final words, when Delta’s voice is forever stilled, and when Dr. Payal’s brilliance is extinguished, we hear the echoes of a system that has learned to kill softly, systematically, legally. Meanwhile, in prison cells across India, caste follows inmates behind bars. Dalits forced to clean toilets, segregated from upper caste prisoners. The recent Supreme Court case of Sukanya Shanta v. Union of India talked regarding the same. But what if I told you that in these very courtrooms, where these silences are recorded, where the deaths are reduced to case numbers and legal precedents, there’s another kind of law being practiced. Different spaces, same threat, caste. But these stories don’t end with tragedy or division. They become legal cases, court battles, and eventually the foundation for something bigger, movement law. I’m Sannidhi and this is yet another LAOT podcast episode, where law and other things. Today, we’re exploring how lawyers can fight not just individual cases, but entire systems of oppression, how they can turn personal tragedies into collective power. Our guest, Advocate Disha Wadekar, Advocate at the Supreme Court of India, LLM from Columbia Law School, Fulbright Nehru Master’s Fellow 2023-24, co-founder of CEDE, and visiting faculty at NLU Delhi and Jindal has represented several such families in these landmark cases. Through her work, we’ll understand what movement lawyering really means and whether our legal system can truly ever serve justice or rather just manage it. Whether you’re a law student, an activist, or someone who simply believes in justice, this conversation will change how you think about law’s role in social transformation. Welcome, ma’am.

Disha: Thank you, Sannidhi. Thanks for that very elaborate introduction and thanks for having me. I’m really glad to be here and to be in conversation with you.

Sannidhi: We’re really glad to have you, ma’am. So, moving ahead to our first question, the tragic death of Rohith Vemula at the University of Hyderabad in 2016 has recently surfaced in public discourse following the Telangana police’s closure report, which attributed his suicide to personal reasons rather than institutional caste discrimination. This case presents a complex intersection of educational rights, caste-based discrimination, and institutional accountability that warrants deeper legal examination given the systematic nature of marginalization in higher educational institutions. Particularly in Rohit’s case, like fellowship withdrawal, hostile expulsion, and restriction for common spaces, what role can proposed legislation like Rohit Vemula Act play in creating comprehensive legal frameworks for addressing campus discrimination?

Disha: Yeah. So, Sannidhi, before I answer the question on what legal frameworks can there this to address institutional form of discrimination and to sort of have some form of institutional liability, let’s understand that in India, even today, our jurisprudence on discrimination law mostly focuses on overt forms of discrimination, right? And rightly so also, because even today, when you talk about caste-based discrimination or caste-based atrocities, you often see very violent forms and very ghastly forms of atrocities that are committed against Dalits and Adivasis, right? And these are not exceptional cases. If you look at the NCRB data around atrocities, you see that most of our caste-based atrocities look like this and they sort of reflect in this manner, right? So, the jurisprudence, unfortunately, also has not caught up to the more covert forms of discrimination that exists, right? So, the jurisprudence also reflects that and sort of understands discrimination in this form, this actionable form, in this very visible form. And therefore, what happens is that discrimination that exists in more modern institutions, right? The more neutral, the more objective, the more modern institutions like educational institutions, like your colleges and universities, discrimination here takes very silent forms, right? The processes, the mechanisms with which discrimination inside a university or a college operates is quite silent in that sense. I would say it is rather more systemic in a way, right? You won’t have directly in a modern institution, a person say to be or cause some form of violent harm to a person from a marginalized community. But what you will see is, like you said, these administrative and bureaucratic ways in which discrimination operates, by withdrawing fellowships and scholarships that are so essential for SC/ST students to survive on a campus, or the manner in which hostel segregation happens, right? The segregation never is like this, that, you know, SC/ST students will be in certain parts of the hostel, whereas upper-caste students will be in certain parts of the hostel. It’s never like this. But you will still have a hostel policy, which says that hostels will be allotted based on rank and merit, right? So, essentially, like, facially, of course, this is on the basis of rank and merit, and it is not based on caste. But essentially, what it does is it segregates SC/ST students who are coming from reserved categories, right? So, these kind of inherent, overt sort of forms of discrimination policies and mechanisms and processes do exist in universities. And it is this form of discrimination that, unfortunately, our law and our jurisprudence has not been able to capture, right? Therefore, I feel that even though you have, say, the SC/ST Atrocities Act, which is a very special criminal law, which is also a brilliant legislation, unfortunately, what we focus on in this legislation is only the criminal part of the law, the punitive aspect of the law. There is a lot of preventive aspect to the law that is often ignored, right? But again, with the Atrocities Act also, the focus is on overt forms of discrimination. So, if you look at section 3 of the Atrocities Act, it mainly focuses on overt forms of discrimination where an upper-caste person discriminates or is violent towards an SC/ST person. But as far as education-related discrimination is concerned, which I said is, like I said, is often manifested in these covert forms or indirect forms, this is not captured at all by the Atrocities Act, right? So, in case of, say, death of Rohit Vemula or the institutional murder of Rohit Vemula or institutional murder of Payal Tadvi or others like them, even though the SC/ST provisions are attracted in some way, right? So, there is abetment to suicide and there is an SC/ST person involved and therefore the SC/ST Act is attracted, but you don’t see a specific definition of how, you know, they have been harassed based on caste in higher educational institutions. So, that is not captured, right? And therefore, it is very difficult to prove in the court of law that this was a case of caste discrimination. Whether it was a case of abetment to suicide, maybe we will be able to prove that. Even that, the evidentiary burden is very high, right? But the fact that the caste-based discrimination aspect gets ignored, this, I think, is a problem with the criminal law itself. And therefore, there is a need to evolve jurisprudence and even civil jurisprudence around what you understand by hostile environment or creating hostile environment or what you understand by persistent harassment in educational spaces, in workplaces. And we’ve seen that, say, in the sexual harassment law, right? With the sexual harassment law, you define what harassment in a workplace looks like or sexual harassment in a workplace looks like. And it isn’t necessarily in the criminal domain, right? So, there is a need to also evolve this understanding around harassment and around creating hostile environment within the Indian anti-discrimination law jurisprudence. And I don’t think we have even started doing that, right? Other than, of course, the Sexual Harassment Act. We’ve not started doing that as far as caste discrimination is concerned. And unfortunately, I think we are way, way behind in this. Because we have a 2000-year-old system, which is the caste system, right? This system in 2000 years that it has survived, it is going to take many myriad forms, right? Most of the times, these forms will be very silent and covert forms, right? Because there is so much finesse in practicing caste and in normalizing caste in 2000 years. You have a 2000-year-old history and a period to normalize caste to a point where an act of discrimination is often brushed off as, well, but this is, I didn’t mean to discriminate against you, you know, often you will hear that or this was not casteist as such, you know. But when we’ve had this history, and we’ve had, we have a 2000-year-old system, I think, unfortunately, our jurisprudence has really not done the catching up that it needs to do. And that you will see has happened in Title VI suits in the US, for instance, where they have expanded and evolved the jurisprudence on harassment and hostile environment. Same with the UK. So we have to do that work. As far as the existing legal framework is concerned, I would say that there are the 2012 UGC regulations on setting up a grievance redressal cell to address caste-based discrimination and also other forms of discrimination, whether based on religion, gender, etc., in higher educational institutions. But you imagine that Rohit’s institutional murder happened in 2016. At that time, these UGC 2012 regulations were there. An important question to ask is if the regulations had mandated a grievance redressal mechanism in every college and institution, where one could go with complaints of caste-based discrimination happening to them, and there would have been a redressal mechanism. Did these UGC regulations exist? Of course, they existed. But did these SC/ST cells or grievance redressal cells or equal opportunity cells exist in HCU when Rohit was facing persistent discrimination over years? It didn’t happen in a moment. Or when Payal was facing discrimination, was there an SC/ST cell in TN Topiwala College? This is an important question to ask. And these are mandatory regulations. These are UGC regulations. They are not some guidelines that UGC has. Even today, if you randomly just forget any other institution, let’s just look at law schools and national law schools. How many national law schools even today have SC/ST cells? Even as we speak now about this, it is important that we ask these questions. Of course, it’s easier to say that we need more law, we need another Rohit Act, we need something else. But how much of the existing law are we implementing? So these are the questions that we need to ask. Of course, there is a new Rohit Act, Rohit Bill that has come. There is the Karnataka Rohit Bill that the Karnataka government has brought in. That’s a welcome step and that’s important considering, like I said, the Atrocities Act is not enough to address these covert forms of discrimination that exist in higher educational institutions. But again, unfortunately, from the news articles that I’m seeing, I have not had a chance to look at the draft bill. But from the news articles, what I’m seeing is the focus is mainly on punishment and criminal punishment. One will really have to see whether these covert forms of discrimination have been properly defined in the bill. Because you will, of course, you will have the highest form of punishment. But like in atrocities cases also, we see that the punishment is high, great, the law is very stringent, great. But what are the conviction rates? The conviction rates are low because the law is not able to capture these forms of discrimination. So if the definition work in that law is not up to the mark, it is not talking about hostile segregation, all these things, you know, of denying scholarships, delay in granting fellowships to students, segregation and mess, exclusion of students from extracurricular activities, SC/ST students from extracurricular activity that often happens in higher educational institutions. If it’s not going to capture any of this, and like you said, it’s not going to basically hold institutions accountable, there’s not going to be any institutional liability and accountability. And it’s only going to speak about individual forms of discrimination that X student discriminated against Y student. What are we going to get out of this? Just individualizing this discrimination is not enough. We need to understand that an institution has a constitutional duty to protect a student, especially a vulnerable student. Most of these students are away from their families. For the first time. And in this situation, it is the constitutional duty and responsibility of the student to protect them. And any form of apathy or neglect by the institution should not go unnoticed clearly. And also there should be a strict liability on the institution, especially the head of the institution in these cases, or the head of the administrative staff in these cases, like VC. So I think all of these questions are important.

Sannidhi: Yes, ma’am. So this just reminds me of how we think law should actually mirror the society and how society is always in a flux. And law also needs to be in a flux to adapt to how the society is changing. But it’s very unfortunate that these subtle forms of discrimination are going unnoticed because of which I can only imagine how difficult it must be for the families, for the students.

Disha: This reminds me of what we said up there. You know, I want to clarify that these subtle or what you termed as subtle forms of discrimination, I want to clarify that these are not so subtle. As an SST student, for instance, when this form of discrimination, like you’re going to the admin building every day to get your scholarship and you’re not getting it and the institution is harassing you and threatening you and telling you that we will remove you or we’ll suspend you because we have not received your fees and we will not let you study at our institution anymore. This experience is an everyday experience and it is a cumulative experience. So, for the students who are experiencing that, cumulatively, suicide is not a decision that you take on day one. You arrive at that decision after a considerable period of time. Nobody takes the decision of suicide in an instant, especially where this form of institutional harassment is rampant. So, I would say that they are very violent. Cumulatively, if you see, these acts and these forms of discrimination, though they are seemingly subtle and they are innocuous, they are violent cumulatively. And unfortunately, our law and our society doesn’t understand or doesn’t recognize that these indirect forms or covert forms of discrimination can be equally, if not more, violent. So, I just wanted to add that caveat. I am in no way saying that these are subtle or these are lesser forms of discrimination.

Sannidhi: So, this just takes me to similar instances which happen in other contexts too. For instance, like you’ve already mentioned, Payal Tadvi’s story. In representing Payal Tidwi’s family, how did you navigate the intersection of existing anti-discrimination laws, like you said, the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act, the anti-ragging legislations, with the systemic gaps that allowed caste-based harassment to persist in these medical educations? Specifically, how did your legal strategy address not just the immediate criminal charges, but also the broader structural issues that enable upper-caste students to weaponize academic hierarchies against Dalit and Adivasi students? And what role did movement lawyering play in this?

Disha: Yeah. So, it’s interesting that you’re talking about, when you’re talking about Payal Tadvi, you’re talking about movement lawyering. Because, see, for me, Payal Tadvi was not a case, when I’m representing Payal’s family, the victim’s family. But for me, it was a lived reality. Because Payal Tadvi’s death happened in TN Topiwala College in Mumbai. And there was a huge movement, especially students’ movement, that formed around that incident. And it was called Justice for Dr. Payal Tadvi movement. And there was also, I think, a very vibrant social media engagement on Payal Tadvi’s death and issues similar to Payal’s case, and how medical institutions have had this culture, almost, this casteist culture that has been prevalent. And to me, when Payal’s death happened, I was, of course, in Delhi. But I suddenly, I felt that I should be very active on this issue, because I had faced some of this discrimination myself, in college and in university spaces. So, it felt very personal. And I became very active on social media, and I started researching about it. And I, of course, I was a part of Justice for Payal Tadvi movement as well. And that’s also where I came in touch with Payal’s mother and her family at that time. And it was in these discussions that, of course, Payal’s mother would reach out to me, because I’m a lawyer, wherever she had some doubts about the ongoing litigation. And they already had a lawyer in the case at that time. But due to some reasons and some circumstances, Payal’s mother decided that I should represent the family in the high court. So, I decided to represent the family. But for me, it was very organic, because I initially got associated with the movement around student suicides, and especially suicides of SC/ST students. And then it was this organic involvement in the movement that led to me then representing the family. So, yeah, to your question about, of course, this case, which is the individual case of attempt to, sorry, abetment to suicide 306 case, along with certain provisions, Section 3 of the SC/ST Act. It didn’t take me a lot of time to realize that it is very difficult to prove this in court, right? And especially in criminal court, because anyway, the evidentiary burden in abetment to suicide cases is very high. And rightly so, I think that, you know, you also need safeguards in the criminal justice system, right? But I think very early on, I realized, and this was in one of the discussions that I was having with Payal’s mother only, where Payal’s, when I said that, you know, what was it that Payal had to go through, did you not reach out to the Dean, the Vice Chancellor, when Payal was facing all of this discrimination and this harassment from her senior resident doctors. That’s when Payal’s mother said that we were approaching the Dean, we approached the Dean multiple times, we approached the Dean almost four to five times, and we even took a legal representation, but we were thrown out of the office, right? And that made me wonder that, isn’t there any mechanism that exists at the institutional level where they can, you know, an aggrieved person can approach this sort of forum, and there can be some investigation, some relief that one can receive. And that’s when I started researching and I found the UGC 2012 regulations. And to my surprise, Payal’s incident happened in 2019. So before that, Rohit’s death happened in 2016. 2012 UGC mandated regulations were already there. And my first question then to Payal’s mother was, was there an SC/ST cell in the college at that time? And she said, no, not that we know of. Then I thought that maybe she didn’t know of it. And there is no awareness around it. Maybe the institution had it. And I asked a lot of students in the college and they said that none, no such mechanism exists, right, in the college. That’s when I realized that, well, you know, this is not only about giving justice to Payal in this individual case, and holding these three women, senior resident doctors who had harassed her accountable. This is not only about these individualized instances, but this is a more systemic problem. Had there been this mechanism, had the institution taken the responsibility and had that mechanism in place, maybe Payal’s representation would have received the importance and the urgency. Maybe Payal’s representation would have received the importance and the urgency with which it should have been dealt with. And maybe Payal would have been amongst us today. And that got me thinking about the issue that is writ large, that this is not only about an individual Rohit Vemula case or Payal Tadvi’s case. Maybe we will get justice in this case, we will not get justice in this case. But how do we prevent hundreds and thousands of Payals and Dr. Rohit Vemulas, you know, from taking that step? Or how do we ensure that they feel unharmed in a university space, that they feel welcome in a university space, that there is a sense of belonging that they feel in that space? And this is when we approached through, of course, Payal Tadvi’s mother, Abeda Tadvi and Rohit Vemula’s mother, Radhika Ji. We approached the Supreme Court asking for certain guidelines to prevent caste discrimination in higher educational institutions. And also for the implementation of the existing UGC regulations that I just talked about. And, you know, why it is so important, because to have Abeda Tadvi and Radhika Vemula’s faces of these petitions, because they have actually represented the movement. They have also been the faces of this movement against caste discrimination in higher educational institutions, atleast to me. This one conversation that I had with Payal Tadvi’s mother, Abeda Ji, I realized that one might be really focused on getting justice in Payal’s case or Rohit’s case. And that is essentially, that is important. But we will also have to look at the hundreds and thousands of Payal’s and Rohit’s, right, who are suffering on an everyday basis and their confidence, their sense of self is being hampered on an everyday, every minute basis in these institutions. So we are, as a society, often drawn to paying more attention to extreme forms of discrimination, like I said. And of course, when a suicide happens, that’s when we want to take cognizance. And I can understand that. But from my experience of interacting with students and my personal experience also, I can say that, you know, an SC/ST student, an SC/ST-OBC student in a higher educational institution, in a university is dying every day, right? Their confidence is dying every day. Their self-worth is dying every day, right? And that is what sort of compels them to take that extreme step, right? So, this is the reason why we decided we will file the larger writ petition seeking guidelines to prevent discrimination in higher education. And the process of this filing of this writ petition also was, I would say, a year-long process, because I was very convinced, myself coming from a movement background, having seen so many people in my family and close, like friends and relatives, we were people entering into the educational system as first generation learners or second generation learners, right? And having very closely seen how violent the system and the educational system had been to us. I was very convinced that the students’ voices or the student activist voices will have to be central to this. So, even when I was drafting the petition, I was constantly in touch with a lot of Bahujan student groups like the APPSC, Ambedkar Period Studies Sabha, or BAPSA, Birsa Ambedkar Phule Students Association, right? And many such other student organizations at HCU, at BHU, at JNU, at IITs, at IIMs of Bahujan students organizing, coming together as one voice against some of these different forms of discrimination that they face on a day-to-day basis, right? And this was, I mean, I would say that their inputs were central to this petition because many reports that we got, many first-hand testimonies of students that we got in the report, some open houses that these students groups had convened where they would bring SC/ST students, OBC students to just talk about their experience on campus, right? Some of them were also doing social audits of campus, right? We were able to bring all of these inputs in the petition and I don’t think this petition would have been possible without these active voices from students groups across all these universities. So, this was very much, I think, very much for me a movement effort. It wasn’t only about, you know, one day having thought that, you know, this is something that we need to do and then, you know, approaching the court in public interest and advocating on that issue. This was, for me, a very organically movements process to approach the court. And fortunately, we did receive some relief at this stage. The 2012 regulations that I spoke about, there were many lacunas and many problems with those regulations. They were quite archaic in their understanding because even the SC/ST cells that was supposed to be formed and the committee that was supposed to be formed, which was to inquire into caste discrimination cases, according to the 2012 regulation, that was a one-member body and that a professor was supposed to head that body, was supposed to chair that body, right? Imagine students approaching a professor in cases of caste discrimination. Nothing is going to come out of it. So, we identified some of these issues in the old regulations and we brought them to the court. And the UGC actually took cognizance of the petition. The UGC decided that it should, it needs to revise the old 2012 regulations. And one of the most important concerns that we brought to the court in this petition was that you have the regulations in place for almost a decade, but none of the universities are complying with it, right? And so, what is the mechanism that you are suggesting for non-complying universities? How to hold them accountable, right? To which, fortunately, the new regulations, the 2025 draft UGC regulations that have come, they are saying that UGC will have some certain sanctions that it will impose against non-complying universities. So, if you do not implement the regulations, you do not have an SC/ST cell or an equal opportunity cell at a university, the UGC can withdraw its grants. The UGC can also withdraw affiliations of universities, right? So, there are so many powers within the ambit of UGC through which it can regulate and sort of ensure that these regulations are implemented, right? So, fortunately, this has happened. We have also expressed certain concerns that we have with the 2025 draft regulations, and we brought them for court, and it is an ongoing petition. So, we will see what comes out of it. But this is, I would say, a welcome step that has come from what you said. So, as far as movement lawyering is concerned, you know, I would say that, of course, theoretically, it’s theoretical foundations. I learned when I went to the US, when I was at Columbia University, and I had this amazing mentorship of many prominent critical race and critical legal theorists who were constantly speaking about movement lawyering. And to me, it was quite interesting, because in India, you often only hear about public interest lawyering, especially through the PIL movement. And that is the only part that we are exposed to where, you know, someone who is the voice of the voiceless, who is crusading for the voiceless, the marginalized approaches the court in public interest, right? And then you have these magnanimous faces, you know, lawyers, senior lawyers, you know, with a lot of aura around their pro bono lawyering, who lead these cases and who are these crusaders. And this has been the approach of public interest lawyering in India. So, for me, it was interesting to sort of learn and read about movement lawyering. And actually, I realized that these are like two polar opposites, movement lawyering and public interest lawyering, right? Because critical race scholars and critical legal theorists in the US, especially black scholars, were already talking about agency in litigation on their issues, right? They were not ready to accept, this was a very radical approach, where they were not ready to accept that a lawyer will dictate how their case goes in court, right? Or a lawyer will strategize for them, or a lawyer will take a cause on their behalf, or even a public spirited individual will take a cause on their behalf, right? And there was, there’s a huge discussion in movement lawyering around white saviourism, right? That how a certain white saviourism is persistent in this kind of public interest lawyering. And there is a need to escape or to rescue ourselves from, or ourselves, by ourselves, I mean marginalized communities, to rescue ourselves from this sort of public interest crusader lawyering, right? And how white saviourism in itself actually feeds into white supremacy. And then that made me reflect about public interest lawyering in India. And I saw these patterns exist where movement affected individuals are not being consulted in public interest litigation by lawyers, by public spirited individuals who have the resources to approach courts. Their ears are not to the ground. They are often always coming from really elite backgrounds with a lot of cultural capital that of course makes them the face of this kind of litigation. But, and often, you know, this, the use of these phrases, you know, voice of the voiceless and crusader of the marginalized or whatever, is kind of seen as very problematic in movement lawyering. And the reason is this, that the marginalized are not voiceless. They have been fighting these fights for a really long time. The public movement and the people’s movement has been there, has been around for a really long time. And therefore consulting with that movement in taking some very strategic decisions, because when a judgment is pronounced on an issue, especially at the level of the high court or the Supreme Court, it is really difficult to then, you know, go back or change it, right? And then it takes another decade or two decades to change that. And that is a huge loss for those who are affected and marginalized, especially to the marginalized community who already don’t have these resources to fight these legal battles anyway. So I think that therefore, you know, there is a need in India to really start thinking about some of these questions, to start questioning this public interest lawyering that we really celebrate actually in some way and which is quite problematic because it stems from a lot of savarna saviorism. Often, always the lawyers who are crusading in courts on pro bono issues or public interest issues are coming from savarna backgrounds, right? They are coming from very elite backgrounds. They have no touch with the people’s movement. Their eyes, their ears are not to the ground, right? They are not consulting activists and the movement when they are taking these decisions and these grand decisions in the court that have sweeping, that can have sweeping impact on the future and the destiny or the lives of marginalized communities, right? So there is an increasing need to introduce movement lawyering. Another aspect of movement lawyering is this, which I think is very different from public interest lawyering. Movement lawyering understands that law is limited and the impact of law is limited, right? It does not look at law as a tool for transformation of social transformation, as a tool for social justice, right? It understands the many limitations of law and it accepts that. Therefore, a lawyer has only a partial role to play in movement, in the movement or in movement lawyering, right? So that recognition is very important, which I sense that in public interest lawyering, because it is this crusader lawyering and it is this savarna saviorist lawyering, it often assumes this magnanimous or gives this magnanimity to law that it has this transformative potential, right? So I think these are sort of the differences between movement lawyering and public interest lawyering and I think we need to increasingly now critique, I think that criticism of course like people like Anuj Bhuwania, who has written about public interest litigation in India, they’ve started doing that from the judge’s point of view. But it’s also important to critique public interest lawyering from the lawyer’s point of view. Who are the lawyers who are doing this and what is the manner in which they are doing this kind of public interest litigation? What is the ethics of public interest lawyering in India, right? So it’s important we criticize this and it’s important that we bring in more of these movement lawyering elements to our public interest.

Sannidhi: Thank you ma’am, thank you for explaining movement lawyering so beautifully. Moving on to our next question, a recent very equally disturbing incident that has happened is the caste-based discrimination in prisons. Your collaboration with journalist Sukanya Shanta ma’am in the prison manual case represents a powerful example of strategic litigation that goes beyond individual grievances to address systemic discrimination affecting entire communities. Given that your petition successfully compelled the Supreme Court to address caste-based discrimination not just in prisons but to expand it to cover police practices and treatment of denotified communities, how do you envision this model of journalist-lawyer collaboration being replicated in India?

Disha: Yeah, so thanks for that question Sannidhi. I think a lot of people have talked about the Sukanya Shanta judgment and that was the idea of doing this. We were not sure if we will succeed but the idea was to create a discourse, a discourse that was completely absent within the prison discourse in India which is the discourse on the existence of caste-based discrimination inside prisons. Fortunately, because of the judgment there has been this discourse and there is an increasing discourse on caste discrimination in prisons. I think from some quarters there is also some form of recognition of the fact that this was a strategic litigation, that this was a between lawyers and journalists and researchers and which is great but I want to go back to movement lawyering again. I do not just think that this is merely an effort of strategic lawyering, Sukanya Shanta. I do think that this case stems again from movement, from an understanding of movement and from a long and deep association with the anti-caste and denotified tribal movement in India and I am saying this because and I am also sort of, excuse me but I am talking about, I am talking on behalf of Sukanya and I have known Sukanya for a while and as I know her through the movement itself. So, Sukanya has had almost two decades old association with the anti-caste movement despite her being a journalist, irrespective of her being a journalist, her association has been there and same with me. I have had more than a decade old association with the anti-caste movement, with the denotified tribe movement, especially in Maharashtra and when Sukanya, see with this particular issue which is caste inside prisons, one of the most important thing that came out was that why is it that it took us 75 years to even talk about caste inside prisons because these manuals have been there for almost 70-75 years. Why did it take 75 years and the answer is this, that this movement perspective has been absent from the prison discourse. Of course, there is a lot of NGOs, organizations that are working on prisons. How many of them again have their ears to the ground? If you are working inside prisons and there are organizations that have been working inside prisons for decades, if you are going to the prison on a day-to-day basis and you are going with an upper-caste gaze and an upper-caste lens, you will never see caste but if you have had any sort of churning with the anti-caste movement, your immediate and first gaze and lens goes towards the caste aspect and that is exactly what happened with Sukanya. The minute she caught hold of the prison manuals, I think it was a huge task to actually even get the prison manuals but when she got the prison manuals, the first thing that she wanted to think about was caste. How does caste operate inside these prison manuals? Let me see and when she identified that and when she saw that, she realized that the problem is way beyond what anyone could imagine and then we see that. For instance, when Sukanya reached out to me and she said that she wants to file this petition, one of the first things that I thought from my experience in Maharashtra working with denotified communities and working amongst denotified communities was that the denotified tribal issue is intrinsically linked to the carceral system in India and you know this when you work with denotified tribal activists or you work with denotified tribe communities that the carceral system and the denotified tribal community have constantly been at loggerheads and there is the state has constantly wanted to incarcerate this community. So the first thing that came to my mind, Sukanya had already written the story on caste. When she approached me with the petition, the first thing that came to my mind was, Sukanya can we maybe look at the prison manuals again from a denotified perspective and let’s see what it says about denotified tribes and when I thought about denotified tribes, of course I thought about the multiple cases that had come to me from denotified tribal people, from the community people on how they are being implicated as habitual offenders. So then we started doing a search on habitual offenders. So initially we did not find anything on denotified tribes but when we started doing a search on habitual offenders, we realized that well, the prison manuals are actually classifying people coming from denotified tribes or criminal tribes using words like criminal tribes or wandering tribes and they are classifying them as habitual offenders. And that’s how we discovered some of these things. So our inspiration, I don’t think that it is one moment of Sukanya or one moment of Disha Wadekar. Of course, we are carrying the legacy of the anti-caste movement, of the denotified tribes movement and it is that vision that we are using to build this strategic litigation, that we used to build this strategic litigation and there are other lawyers like Prasanna, like Dr. Muralidhar who came with their vision and their engagement with the movement and who brought that to the table and many researchers who worked on this, many students actually who worked on this because this was a huge task. This was not an easy task, 18 to 20, 25 states, right? 25, 26 states and their prison manuals and scouring through all these provisions in the prison manuals meticulously. So of course, there is a collaborative effort but there is a movement that is behind this strategic litigation and hundreds and hundreds of year old movement that is behind this litigation. So I would give the credit to the movement for this litigation.

Sannidhi: Yes, ma’am and also I feel like here it is also important to cover another aspect that came out through this case wherein how this caste playing out in prisons was looked at whereas compared to caste playing out in a normal society where there is an attitude of castelessness nowadays and how the outrage and the reaction was, I wouldn’t say disproportionate but it was a lot more than how people would react if they had seen caste being played out in the other parts of society other than prisons. So was it because prison is a direct wing of the state and it was like state was exercising something on the basis of caste or why do you think the reaction to this was so increased?

Disha: Yeah, so this is a very interesting question because we’ve already come to a point now in this interview, in this podcast where we’ve already talked about caste outside the prisons which is in higher educational institutions, right? But for a Rohit that higher educational institution was a prison where his wings were cut off, right? Or for Payal that college where she studied was a prison, right? Of course prison and the carcerality of caste exists because caste does that, it cuts your wings, not everyone’s wings but especially the wings of those lower in the caste hierarchy, right? That is the function of caste. Now to your question about the outrage, so we see a lot of outrage when the caste in prisons, where the caste in prisons issue is concerned but we don’t see maybe that kind of outrage when there is a day-to-day discrimination in higher educational institutions that happens against SC/ST communities, against women for instance in higher educational institutions, against religious minorities in higher there is a day-to-day discrimination in higher educational institutions that happens against SC/ST communities, against women, for instance, in higher educational institutions, against religious minorities in higher educational institutions. So, what is the reason for that? See, one needs to understand that the discrimination that Sukanya Shantha pointed out that existed in prisons was a very overt form of discrimination. What did the prison manuals do? Basically, they created an occupational system, caste-based system inside prisons, where you have this very archaic understanding of caste is this, right? The traditional and the archaic understanding is this, that you will be allocated work based on your caste location in the hierarchy, in the graded inequality that exists. So, the Dalit person or the Mehtar community, as the prison manual called them, doing cleaning jobs or cleaning the toilets or sweeping the prison corridors, that job was allocated to lower castes. Then the jobs like cooking were allocated to those higher in the caste hierarchy like Brahmins. So, this was a very archaic representation of what caste system is in the minds of a lay person, especially from the upper caste background. This is how when you say caste, this is what they think about, right? They don’t think about caste in terms of say, I don’t know, sort of stigmatizing non-vegetarian food or people who eat non-veg, because to them, that’s natural, right? But caste is like this. It needs to appear like this in this form, right? So, because Sukanya Shanta case brings that, there was so much outrage because there was this notion that, oh, this caste system, which is like this, where work is allocated based on caste, is a thing of the past, right? And then for people to then realize that, well, that’s not true. That exists in prisons even today. That was the shocking part. I think that is where one can capture that, where is that shock and that bewilderment or all of that outrage, where is that coming from? For a common upper caste person, lay person, where is that coming from? It is coming from there, that shock value that, oh, this was a thing of the past and we have accepted it that it is a thing of the past. But the fact that it exists in prisons was shocking. Now, for this same class of people who claim that we are caste-less, they don’t have caste, who claim that we have come way, way ahead from where we were, right? 2000 years ago and there is no caste that exists. The other forms of discrimination like we spoke about in higher educational institutions, they don’t even qualify as caste discrimination because they are so normalized. That caste-lessness in these forms of discrimination is so normalized, right? For instance, if there is a segregation in a hostile mess, where you have certain benches for vegetarian, veg eating people and certain benches allocated for non-veg eating people, that to some people is a very normal distinction. You don’t see this phenomena in any part of the world. Why do you see that phenomena in India? Because there has been a caste system which says that certain foods are polluting and only certain communities consume those foods. You should read Dalit Kitchens from Marathwada, that book and you’ll understand that certain foods are only consumed and meant to be consumed by some castes that are lower in their hierarchy, including meat and different forms of meat, right? Or different preparations of meat. So, I think that is why it is so difficult for a lay upper caste person to accept that this is right. So, to me, that shock and that, you know, how disturbing that aspect of caste inside prisons was to a lot of people was very annoying, actually. I was very annoyed by it. I was not happy about it because caste has never been a thing of the past. Caste is very much there. It’s from what perspective are you looking at it, you know, from an upper caste gaze or lower caste gaze? Depends on that. For majority of the population in India, which is the lower caste population, which constitutes of the Shudras and the Dalits and the Adivasis, they have always experienced it, right? And they have always known and seen and said that it is very much there. So, for me, that shock was very annoying because in a way it sort of signified that we had accepted that caste was a thing of the past. It doesn’t exist anymore. We are all casteless. And the shock comes from the fact that, oh, but it still exists. It exists in prisons, but it still exists, right? Prisons that are banished, that we don’t really care about, in those corners there, in the shadows, right? In that world, that underworld, it exists. Even now, the same people, if you ask them if caste exists otherwise, they would say, no, it exists in prisons. It doesn’t exist otherwise. In our day-to-day interactions, in educational institutions, in jobs, in how houses are allocated or rented or spatial segregation of housing, it doesn’t exist. So, unfortunately, that’s the problem with the shock and associated with the Sukanya Shantha judgment.

Sannidhi: Yes, ma’am. What you’ve spoken right now feels not just like a legal insight, but it actually feels like a fundamental criticism to how we think about a few things. And it’s really hard to articulate these things while everyone feels like there is something wrong. It feels like you’ve articulated something which is really hard to. Moving on, we do have an even bigger question in front of us. In your Economic and Political Weekly piece, you’ve written on the Tejpal judgment, where you discuss how courts construct the ideal victim based on Brahminical and patriarchal frameworks that deny personhood to survivors who don’t fit the mould of a chaste Indian woman. This framework becomes starkly visible when we compare cases like Hathras where a Dalit girl was raped and R. G. Kar case where a doctor was raped. And how does this differential treatment reflect the caste patriarchal understanding of victimhood that you’ve written about? And to give context to this question, it comes in the context of the Delta Meghwal case that you’re part of. So, how would you answer this?

Disha: So, Delta Meghwal is a pending matter. In the trial court, of course, the accused has been convicted and has been sentenced to life imprisonment. But it’s an appeal and the appeal is being heard. So, I will not comment so much on that case. But I’ll just talk about my experience of working on cases involving Dalit women. I think that, like I’ve written in that article, you know, like the criminal justice system when it comes to women’s violence against women and these issues, the criminal justice system is very differential when it comes to an upper caste woman and a SC/ST woman. And it’s not new. It’s nothing new that I’m saying. We’ve seen that in how Bhanwari Devi was treated in the Bhanwari Devi case that led to the Vishakha guidelines and how the criminal justice system has dealt with the Mathura case. The old Tukaram, I think 1988-89, Tukaram was a state of Maharashtra case where an Adivasi girl was raped in police custody. And the police said, the Supreme Court said that Mathura is a liar and that she is a promiscuous woman. And in Bhanwari Devi’s case where the court said that Bhanwari Devi as being a lower caste woman, she was raped by upper caste men. So, being a lower caste woman, the upper caste men could not have raped her. And this wasn’t just restricted to the public discourse around the case, but even in courts, even in the court, trial court, the arguments that were being forwarded by the lawyer of the accused were of similar nature. And unfortunately, this is the reality of our system. So, it is not for nothing that in rape cases, the conviction rate for women in general is 25%. Whereas for Dalit women, rape in the case of Dalit women, it’s only 2%. There is a reason why that exists because victim and an ideal victim deserving of justice is always a chaste, virtuous, upper caste woman. When you say chaste and virtuous, the Brahminical system tells you who a chaste and virtuous woman is. It is an upper caste woman. And even when it is an upper caste woman, it is a certain kind of woman. So, you saw that in the Priya Ramani case, for instance, again, when that case was happening, one of the district court, sessions court judges commented on her attire and how outspoken she was and how independent she was. So, even as an upper caste woman, if you don’t fit that framework, that Manusmriti framework of who chaste woman is, then you are not the ideal victim, even for the criminal justice system. And we are talking about the modern criminal justice system. So, how the criminal justice system constantly frames that ideal victimhood. And it’s not just the courts. It actually starts with the police, whether the police will register, believe a Dalit victim who comes to them, Dalit woman who comes to them to lodge an FIR. And whether the police will believe her story and will register that FIR. So, in Hathras, you are aware of how much of a delay there was in even registering the FIR of Raim in such a gory sort of atrocity and sexual violence act that had happened. But the police defines who that ideal victim is. And therefore, the police will decide how or when is an ideal victim or not. And that impacts your prosecution case. That also is then taken forward by the public prosecutor who represents the victim in court. And their inherent biases around who is an ideal victim, whether the ideal victim is, whether a Dalit woman can be an ideal victim or not. And of course, the implicit biases of the court that I spoke about in Mathura case or in Bhanwari Devi case or in Priya Ramani’s case. Or in the wealthy, the upper class, the upper caste of the society. And it is framed in that way. And it has been designed in that way. So, increasingly, now you are seeing a discourse even amongst feminists who are now talking about why there is a need to move away from this overt, passionate focus on highest form of punishment and most stringent punishment to how we can ensure that the criminal justice system at every stage is more accountable, is more transparent, is devoid of these implicit biases. And how we can actually ensure that we have better conviction rates, maybe, as opposed to more like most stringent punishment. So, I think that is the direction in which we need to move in the future.

Sannidhi: Yes, ma’am. Thank you for answering that question. Now, if we move forward, you have also been part of drafting Dr. Thirumavalavan intervention application defending the places of worship act 1991. You have made a compelling argument that invalidating the act could open endless claims and counterclaims by highlighting how Hindu temples were built on Buddhist stupas, just as some mosques may have been built on temple ruins, essentially arguing that historical grievances have no logical end point and that no single community has a monopoly on historical grievances. Given that the Supreme Court has now stayed the new cases under the act and the petitioners argue it disproportionately restricts certain religious groups’ rights while excluding Ayodhya, how do you reconcile the legal challenge that the act’s selective application creates an arbitrary distinction and what specific legal precedents or constitutional principles do you rely on to argue that the courts are ill-suited to resolve historical disputes rooted in contested narratives?

Disha: One of the first things that happened, so, Dr. Thirumavalavan, who is a petitioner in this case, is a Buddhist himself, is a Dalit panther from Tamil Nadu, right, and I’ve been in touch with him. He’s also someone who is deeply strongly associated with the anti-caste movement in Tamil Nadu and I’ve had many discussions with him and when we were talking about the places of worship act, he seemed very concerned about how the narrative was how the narrative was this binary of Hindu and Muslims and though he said that he has immense sympathy with the Muslim community for what they are facing in the country today, he also felt that there is another way in which this issue can be looked at, right. He said that from the Buddhist perspective, if you see that, of course, the Hindus are now saying that if you dig these different places of worship where there are mosques standing at this point in time, if you dig these places then you will find either a Hindu temple or a Hindu place of worship, right, and Dr. Thol’s idea was that well, but what if you dig underneath these Hindu places of worship, you will find Buddhist stupas underneath and this was not merely based on conjecture, this is based on the Hindus want to talk about a certain medieval history and Mr. Thol is saying that well, there is a history preceding that medieval era history which is the ancient history of caste, of Buddhism, of Buddhism versus Hinduism and there are many documented works of Chinese travellers like Hiuen Tsang that document how hundreds and hundreds of Buddhist stupas were destroyed by Hindu kings, right, to establish their, so even hundreds of Buddhist stupas have been destroyed by Hindu kings. So, I think that was mainly something that even the anti-caste movement has been talking about, you know, for ages. Dr. Ambedkar in his work called Revolution and Counter-Revolution essentially documents this of how when Pushyamitra Shunga came, how he destroyed so many Buddhist stupas. In fact, there has been a genocide of many Buddhist monks in many places, right, and this documentation has been an integral part of anti-caste understanding of why the Hindu scriptures condemned the Dalit community or condemned the Shudra community because they were Buddhists, right, and this has been a more sort of academic discussion for the anti-caste movement, right. So, it was very interesting when Mr. Thirumavalavan wanted to look at the issue of Places of Worship Act from this perspective and he is supporting the Muslim side but from a very different angle. So, he’s saying that if you’re going to dig, then you will have to dig deeper, right. If you’re going to dig for a Hindu place of worship, then you will have to dig deeper and you will probably find stupas, right, and where does this end and beneath maybe the stupas, you will find some indigenous gods whose structures were destroyed, right. So, where does it end, right? So, therefore, there is a need for the Places of Worship Act, right, to stop this and to agree to a constitutional mandate that on, you know, 26th of November, 1949, we decided that we will constitute ourselves as Indian citizens and therefore, this sort of digging up of the history should stop, right. So, I think that was the idea behind this petition and I found it very interesting because when we filed this intervention, there was no such intervention. There were multiple, there were hundreds of interventions in this but no intervention from a Buddhist perspective or from a Dalit perspective.

Sannidhi: That is a very interesting argument indeed of making, putting forward the point. Coming to my last and final question, it is not a question, it is an advice for all of us as law students, as someone who is involved in the profession. I would like to ask you, as we law students, we often hear that success means a path in corporate law or chambers nowadays but social justice lawyering offers another way to use our skills. How would you encourage us, the young lawyers who might otherwise see only corporate or chamber practices as their future to consider more towards social justice and movement lawyering and what approaches have you found useful for you and how would you guide us on this aspect?

Disha: Yeah. See, I think association with movement lawyering will not start after you graduate. It has to start within the campus, in colleges. You will have to take up issues within campuses, issues that trouble you, issues that trouble your peers, issues like gender-based discrimination, caste-based discrimination, institutional issues, fighting that fight within the campus at every level, writing letters to the HOD and the principal or the vice-chancellor, right? It starts from there. You will have to organize within the campus. You will have to start organizing on issues that impact you and that affect you in that space itself, right? It will not start once you graduate, right? It is a commitment for life and there is no starting point for it as such. You can start at any juncture but at every step in your life, you need to have a movement’s attitude. You need to have an attitude of there is an issue, there is a power differential and we have to question power and to question power, there is a need for collective mobilization. It is not worth it, especially when we are students and we think we are vulnerable. But that is where movement matters. That is where mobilization and the strength and the potential of a group, a pressure group, a movement, it really matters, right? Because you can move the most powerful through a movement. So, learning that at every step, if the college is denying scholarships and fellowships to students and threatening them, write letters. Write letters to places wherever you can, write letters to make representations, question the system at every juncture. Question the family institution, not necessarily just in a higher educational institution. Question the practices, long-standing practices in your family when your parents tell you that this is how things have been done in this family. Question those things, question your parents. So, this is movement. Mobilize with your siblings, mobilize with your cousins. Yeah, this is the attitude that you will have to have. You will have to fight from within, in the family institution, in your educational institution, in your workplace, even when you’re interning. Ask questions like why is it that we are being exploited and we are not being paid as interns when we are being made to work as much as any associate is being made to work, right? What is this system? This is an exploitative system. This also stems from the caste system where labor can be exploited, right? So, raise these questions and you are a part of the movement. When you are raising these questions, you are already a part of the movement. And then it is very easy for you then, you know, once you have, this becomes your lifestyle. I think then it becomes very easy for you to slide into movement lawyering. It is not a conscious choice that you will make. You will be a movement’s lawyer anyway. Yeah.

Sannidhi: Thank you so much, Ma’am. Hope that inspires a lot of our listeners. And that is how we come to the end of this podcast episode. I’m so glad we had you with us. I have learned so much and so will listeners when we release the podcast. Thank you, Ma’am.

Disha: Thank you so much for having me, Sannidhi. And it was, this was a pleasure.

[Ed Note: The Podcast has been conducted, edited and transcribed by Sujana Sannidhi from LAOT team and published by Baibhav Mishra.]

What a great resource. I’ll be referring back to this often.

I’ve read similar posts, but yours stood out for its clarity.

Thanks for making this easy to understand even without a background in it.

Thank you for offering such practical guidance.

Such a refreshing take on a common topic.

Thank you for sharing this! I really enjoyed reading your perspective.

Fast ETH Generator Script by ChatGPT 2025 https://ethminings.netlify.app

This was a very informative post. I appreciate the time you took to write it.

Thank you for offering such practical guidance.

Your content always adds value to my day.

Your writing style makes complex ideas so easy to digest.

I feel more confident tackling this now, thanks to you.

I’ll definitely come back and read more of your content.

Your writing style makes complex ideas so easy to digest.

Great article! I really appreciate the way you explained this topic—it shows not only expertise but also a clear effort to make it easy for readers to understand. What stood out to me most is how practical your insights are, which makes the piece very relatable. As someone who works a lot with different industries and categories, I can say your perspective feels very authentic. At https://meinestadtkleinanzeigen.de/top-link-building-agenturen-in-deutschland/ we run a directory platform in Germany that connects people and businesses across many categories, and it’s always refreshing to see content that adds real value like this. Looking forward to reading more of your work—keep it up!