[Ed Note: Over the next few weeks, we will run a book discussion on Danish Sheikh’s Love and Reparation: A Theatrical Response to Section 377 in India. This is the introductory post by Douglas McDonald.]

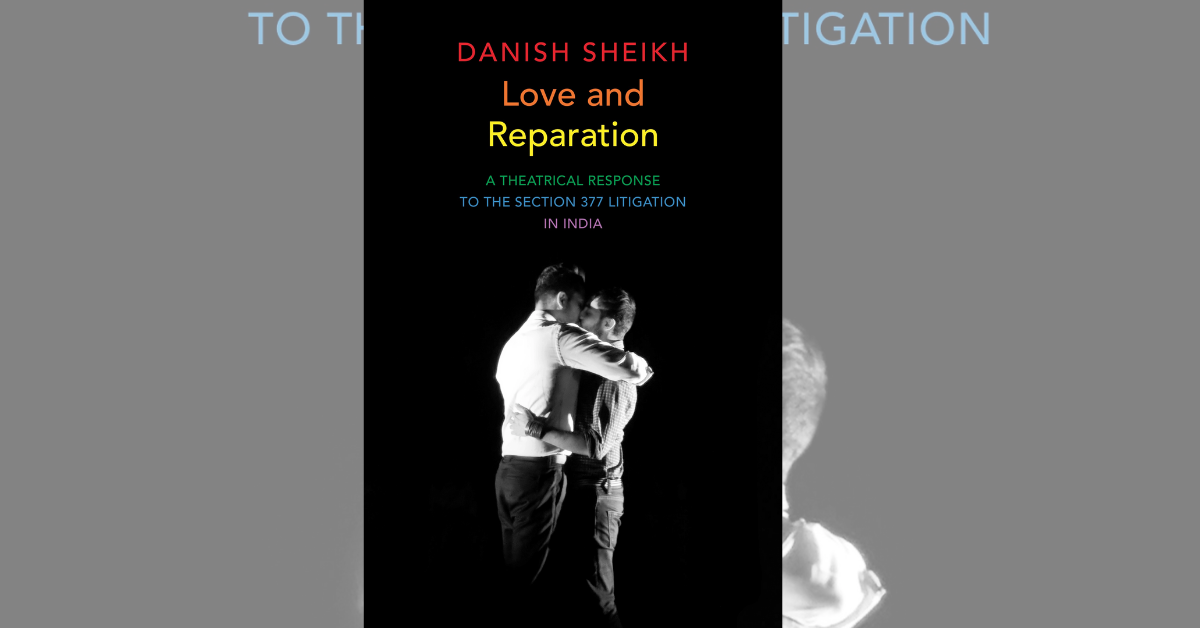

Danish Sheikh is a lawyer and a playwright; his twin careers operate in concert. In particular, his theatrical work is strongly informed by his involvement in the long campaign against section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. His new book, Love and Reparation: A Theatrical Response to the Section 377 Litigation in India (Seagull Books, 2021), further develops his work in both spheres. On both the macro level (his use of theatre as a tool for pedagogy and activism) and the micro level (repeated references to Harry Potter), this book captures the essence of Danish Sheikh.

Love and Reparation contains two plays by Sheikh: “Contempt” and “Pride”. Both must be read in their historical and legal context.

“Contempt” and Suresh Kumar Koushal

In alternating scenes, “Contempt” contrasts an edited and revised account of the Supreme Court’s hearings in the matter of Suresh Kumar Koushal v. Naz Foundation. This is done with the accounts of four witnesses – queer people in India speaking of love, shame, heartbreak, and exclusion. Initially staged in counterpoint to one another, in the final scene the sterility and cold intolerance of the bench interrupts the witnesses’ chorus – before the bench is in turn drowned out by the voices of the witnesses. They are not silenced by the Court’s final proclamations as to the constitutionality of Section 377.

The first draft of “Contempt” was written in 2016. The play is not just a reaction to the outcome in Suresh Kumar Koushal, but to how the judgment was reached at. Sheikh’s account of the Suresh Kumar Koushal hearings is revised and restructured, but readily evokes the discursive, frustrating, and frequently baffling unofficial transcript of those hearings. In the judgment, Justice Mukhopadhaya focused obsessively upon the bare text of Section 377 absent history or context (‘A mother puts her fist in the mouth of her child – Is that penetration? Cannot say?’; ‘What about hugging? Male/female, male/male hugging is not a taboo. Some acts may attract attention of 377, some may not. Which act is in your pleading?’; ‘Would breast feeding come within the meaning of carnal intercourse, what is carnal intercourse?’) and upon the character of the acts prohibited rather than the community adversely affected by that prohibition (‘we are talking about sexual acts – those are not in the minority or majority’). As Sheikh and Siddharth Narrain wrote in the aftermath of the judgment in Suresh Kumar Koushal, the question of ‘what acts constituted “carnal intercourse against the order of nature”… was posed to just about every advocate’ who appeared before the Court. Further, Justice Singhvi’s absurd hypothetical during the Suresh Kumar Koushal hearings about ‘a peculiar incident in Punjab’ – in which three women were ‘engraved’ with tattoos on their foreheads to mark them as pickpockets, and which was raised as an apparent analogy to the discriminatory treatment of sexual minorities in India – is reproduced almost verbatim in “Contempt”.

The fixation of the Court on these narrow questions was reflected in the Suresh Kumar Koushal judgment – in which the Court recognised and protected the question-begging distinction ‘between carnal intercourse ordinarily and carnal intercourse against the order of nature’ as a rational and intelligible differentiation In this judgment, the Court also notoriously relied upon the assumptions that only a ‘miniscule fraction of the country’s population constitute lesbians, gays, bisexuals or transgenders’ and that only a very small number of prosecutions had occurred under Section 377 (despite the enormous body of evidence before the Court as to the scale of abuses under the clause). As Sheikh and Narrain wrote at the time, ‘[t]o indicate that an oppressed group needs to achieve some kind of minimum number before approaching the Court for relief betrays a complete misunderstanding of its role as a counter-majoritarian institution’.

“Contempt” hence amplifies those voices and perspectives ignored or belittled by the Supreme Court, illustrating the gulf between lived experiences and the deafness of the bench. The witnesses’ final plea – ‘And yet. I need you to understand… [N]o, not understand. I need to take you … there’ – is an attempt to transcend this gulf, to reject the narrowness and abstraction of the judgment in Suresh Kumar Koushal, and to use theatrical devices to promote a vision of law capable of understanding and protecting acts of love.

“Pride” and Navtej Singh Johar

“Pride” is a more explicitly personal and conceptually daring work. The play’s prologue depicts extracts from argument and judgment in Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India – a stirring set of proclamations that conclude the legal drama depicted in “Contempt”. But that is, of course, not the end of the story. From there, “Pride” is again a story told in alternating sections: the unnamed “A” and his therapy sessions with Tarini, contrasted against “Interludes” containing the voices of five queer Indians. Unlike in “Contempt”, where the four witnesses largely spoke in monologue, the five speakers of the “Interludes” do not speak uninterrupted: they interrupt each other, they question each other’s narratives, they challenge each other and hold one another to account. (The speakers’ discussion of the meaning and implications of Navtej Singh Johar ultimately descends into a shouting match. Anyone who has spent time in activist spaces should find these scenes familiar.)

But, like “Contempt”, “Pride” ends with a note of harmony. “A”’s quest for a ‘grand unifying narrative’ collides with the voices of the five speakers, as they argue about what Navtej Singh Johar was really about: a ‘case about bringing people’s lives into the courtroom’? A case built on ignoring lived experiences of persecution and exclusion by those outside a high-caste high-class domain? A case about ‘how people can have conversations in spaces where it wasn’t possible’, about ‘honouring the decades of struggle that got us here’, or about ‘how we get to gay marriage’? “A”’s tortured journey towards self-acceptance, mental health and love coincides with a moment of consensus between the five speakers – that ‘[w]e actually won this huge massive victory and whatever happens next it won’t change the fact that we won’. Even if the speakers may never agree on anything ever again, on the day of the judgment, ‘that day, it felt like nothing could stop us.’ This suggests the long wait for the end of Section 377 has come to an end – with speakers and “A” together standing before the audience, to declare ‘that we are done waiting’.

Navtej Singh Johar, as demonstrated in the play, is part of the struggle, not its end. The judgment undoubtedly differs sharply in both outcome and style from Suresh Kumar Koushal – drawing upon literature, sociology and judgments from a wide range of other jurisdictions. Unlike Suresh Kumar Koushal, parts of Navtej Singh Johar look beyond the bare text of Section 377 at the way in which the section has been used and its broader social effect – that ‘[s]tatutes like section 377 give people ammunition to say “this is what a man is” by giving them a law which says “this is what a man is not”’, and in so doing perpetuate ‘a culture of silence and stigmatisation’ (Chandrachud J at [47] and [52]).

But Navtej Singh Johar is not of itself an answer to the damage already inflicted by Section 377 (or the social attitudes to which Section 377 gives voice), nor do all sexual minorities within India equally enjoy its benefits. “Pride” does not elide these complex questions; indeed, they still lie at the heart of the play. But, just as “Contempt” evokes a particular moment of despair and resolve in the aftermath of Suresh Kumar Koushal, so too “Pride” is a snapshot of a moment after Navtej Singh Johar when new things seemed possible.

Danish Sheikh uses theatre as a form of legal advocacy and persuasion, holding settled doctrine up for critique and ridicule through satire and sincerity. His work speaks to the role of law in shaping how individuals understand themselves and their society. I am delighted that this roundtable has chosen to explore his work.

We are pleased that the following people will contribute to the discussion Love and Reparation, which will be followed by a response from Danish Sheikh.

Akhil Kang – PhD candidate in Socio-cultural Anthropology, Cornell University- The Review can be read here.

Kriti Sharma – Assistant Professor, Jindal Global Law School- The Review can be read here.

Surabhi Shukla – DPhil (law) student, Oxford University- The Review can be read here.

This book discussion has been co-edited and coordinated by Anushree Verma and Gayatri Gupta from our Student Editorial Team. You can follow Law and Other Things on our social media handles. (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram)

[…] [Ed Note: Over the next few days, we shall be discussing Danish Sheikh’s new book, Love and Reparation: A Theatrical Response to the Section 377 Litigation in India (Seagull Books, 2021). This is the third review of the book by Kriti Sharma. The introductory post by Douglas McDonald and other reviews can be found here.] […]

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me. https://www.binance.com/sk/register?ref=OMM3XK51