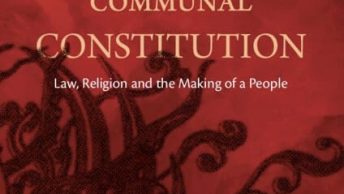

In this, the second part of my review of India’s Communal Constitution: Law, Religion and the Making of a People” (“Communal Constitution”), I propose to go in some depth into Mathew John’s The Communal Constitution, specifically its core argument about the interaction between religion and the Constitution, and its colonial antecedents.

First, I want to air a personal grouse only somewhat related to John’s book – Indian constitutional law practitioners and academics’ being reluctant to look at non-judicial sources of constitutional law and practice. This is not a fault peculiar to John but the Communal Constitution does succumb to it. There’s an underlying assumption that constitutional law in India is what the Supreme Court of India (“SC”) says it is and the task of the academic is to largely make sense of what the SC has said on the matter. This is a larger methodological problem with the field in my view – claims about the Indian Constitution rely too heavily on the (all too inconsistent and contradictory) judgments of the SC and occasionally High Courts (“HC”). While such an approach has its uses, I am increasingly becoming more sceptical of claims about what the Constitution of India is or says simply because the SC has, in some judgment or ten, said so.

Expanding the scope of how constitutional law develops would’ve definitely added to the Communal Constitution as I will explain in the coming paragraphs. The politicians who were in the Constituent Assembly did not just quietly slip away into obscurity once their task was done – they continued to be in active politics, shaping and re-shaping the way the Constitution was worked in the years. Not just politics but social movements, academic research and even bureaucratic practices have influenced the way the Constitution has been understood and applied. To take but one example – the appointment of judges can partially be understood if one reads the judgments in the Second and Third Judges cases but to understand how appointment of judges actually took place and how they have changed over time, one will need to look at the practices that are described in George H Gadbois’ book. Similarly, Articles 123 and 213 will not tell us as much about the appointment of judges post 2014 as reading the collegium’s resolutions, the controversies over appointment and the memorandum of procedure which dictates the process. These tell us the current state of constitutional practice rather than how the judges in the 90s would have liked it to be.

Within the scope of this review, I wish to address three main themes dealt with by John – constitutional protection for religious practices, customary “law”, and the set complex question of caste and religion. Unless otherwise stated, I don’t fundamentally disagree with John on the colonial influence on the Constitution’s idea of Hindus and Muslims. To clarify – I would argue that the institutions inherited from colonial rule and charged with the working of a democratic constitution still “see” people in a colonial way. This is not just in the context of religion but in a host of other contexts that has a fundamental bearing on the way the Constitution of India has been interpreted and put into practice.

1. Essential Religious Practices (“ERP”) and constitutional morality

John doesn’t think the ERP test was per se flawed or the wrong way to interpret the scope of Article 25 and 26. The ERP test was a judicial innovation that helped courts address what sort of *practices* (as opposed to beliefs) would be constitutionally protected. The ERP evolved also at a time when the courts had a narrow and restricted approach to the interpretation of the scope of Part III of the Constitution (as seen most famously in the AK Gopalan case). A fundamental rights claim (it was wrongly believed) could only rest on one article or another of Part III.

ERP as it started was a reasonable way to see what was protected constitutionally and what was not within Articles 25 and 26. However, what is sometimes missed is that it evolved at a time when constitutional cases did not always start in the HCs and the SC and get decided on the basis of affidavits alone. Rather, such cases also started in trial courts and other fora where facts could be established on the basis of well recognised principles of evidence and civil procedure. At some point that stopped happening and HCs and SCs decided everything should be done through affidavits. In cases where the facts are undisputed, this is not so much of a problem. Where, however, there are serious disputes on the facts, adjudicating the issues of constitutional law without being certain of the facts leads to disastrous consequences. In some cases it involves blindly accepting whatever version of the “truth” the government supplies (as in the Loya case). In other cases, it leads to the muddle that is the Sabarimala judgment.

The Sabarimala case, in my view, was a simple matter of administrative law and statutory interpretation – did the Devaswom Board have the delegated legislative power to forbid women of a certain age from the temple. A plain reading of the Act would suggest not – this finding is made and the matter could’ve ended there. However, the Court proceeded to go beyond and worse, on contentious facts leading to a completely incoherent finding about constitutional morality. While I believed then that this was the right step, over the years I am more convinced that this was perhaps not the right way to go.

This is not just a theoretical dispute one has with the Court’s approach to the Sabarimala case. Constitutional morality is a well understood concept that calls on officials to act in a manner dictated by the law and the Constitution. It is not a unique set of principles and values that lawmakers have to abide by. It is highly doubtful if this idea, articulated with an individual bureaucrat in mind can be extrapolated to the functioning of an institution such as parliament let alone be a sound basis for judicial review of legislation. At a very trivial level it means nothing more than laws made by legislators should adhere to the Constitution – but that doesn’t tell us the limits the Constitution imposes on the legislature.

What then is constitutional morality in the context of the right to religion? In the Sabarimala judgment it is a fairly empty construct – its content being determined by whatever a judge or bench of judges thinks “constitutional”. It is an altogether subjective test claiming the veneer of legitimacy, applied by a judiciary unaccountable to any institution and historically dominated by majority communities and the privileged, is a recipe for disaster. It risks turning constitutionalism into a religious dogma by itself but this time enforced by the writ of the government.

This may be far-fetched but much worse has been done by the SC in unaccountable exercise of its vast powers (as Anuj Bhuwania points out in “Courting the People”) and one must be suspicious of justifications offered that expand the court’s interpretive role to determine what is constitutionally protected religion and what is not, purely on subjective grounds. Where there are certainly flaws in the way in which the ERP test is being applied today, it is still a preferable option to a completely open-ended fact free exercise of using a conceptually empty test of “constitutional morality” to determine the scope of the right to hold religious beliefs and practice religion. Perhaps the SC needs to retrace its steps in the matter of the ERP test, taking the process of fact finding in religious practices more seriously, giving greater scope for gathering and weighing evidence about a certain practice rather than relying on thinly supported affidavits or just reading of religious texts.

2. Custom, personal laws and the modern bureaucratic state

John makes a very interesting argument about the development of Anglo-Hindu and Anglo-Muhammadan personal laws during British Rules in the second chapter of his book.

However, the “Anglo” contribution to the development of “Anglo-Hindu” and “Anglo-Muhammadan” law was purely by accident. While we can see intentionality in the colonial government’s intervention in the abolition of sati and child marriage (to name a couple of reform measures), the judicial evolution of religious personal law was an accidental by-product of colonial rule. English courts helmed by English lawyers and civil servants were called upon to decide questions of marriage, divorce, succession, adoption et al largely in the context of pension benefits of soldiers and governments or in the context of zamindari.

John points out that this was not an inevitable development of law but a contingent one – that it was a conscious choice made by the British judges and civil servants to choose to apply shastric Hindu law or Quranic law instead of local custom. The main proponent of customary practices as “family law” James Nelson cuts a lonely figure in challenging the mainstream dogma that Indian family law should be found in some religious text or the other.

John’s fascinating account of this debate is both illuminating and perceptive in subtly exposing the kinds of choices made by the colonial regime in creating a body of law that is ostensibly “organic” in its growth and evolution but in reality hides a certain intentionality in action.

However, there might be another way to approach it. Colonial rule was the first experience of the modern bureaucratic state in India. As Max Weber first pointed out, the distinguishing feature of the modern bureaucratic state is its need for rules and certainty. Seen from this perspective, in societies with low levels of literacy and widely disparate practices, religious texts were perhaps the next best thing to create some sort of uniform body of loan which could be applied across the land.

Indeed this justification does come through in some places but one can of course raise the very important question that John does – how did the British decide who was a Hindu and who was a Muslim. All the criticism levelled at the manner in which Anglo Hindu and Anglo Muhammadan law is probably valid (including Jinnah’s pithy denunciation of it). However, would an alternate universe, where Nelson’s idea of family law driven only by custom, necessarily lead to a “better” world in some way?

We don’t have to imagine because even as shastric Hindu law was being applied to communities, adivasis in the Chhota Nagpur plateau followed their own customs – a right protected by statute. Post the coming into force of the Constitution, another variant of the debate between custom and religious prescription was reproduced in the context of Maki Bui as described in the SC’s judgment in Madhu Kishwar v State of Bihar. The question boiled down to – should Adivasis be compelled to follow statutory “Hindu” law which is ostensibly more gender just than their own practices? There is no easy answer and the Court’s conclusion remains unsatisfactory – something Madhu Kishwar herself acknowledges.

I do not offer any answers but only wish to complicate the debate – something that is perhaps necessary in the context of the binary that has been drawn in the context of the debate over a Uniform Civil Code. Framed purely as a Hindu versus Muslim issue it fits within John’s core argument about the communal aspects of India’s Constitution. Adding elements of women’s rights, individual autonomy, constitutional guarantees of autonomy for tribal communities, and the Indian state’s complicated history with its tribal communities is necessary. The Hindutva movement would prefer that all these issues be ignored and the Uniform Civil Code turned into a Hindu – Muslim and it is wise perhaps to break out of that false binary in order for a truly progressive family law code to emerge in India.

3. Caste and Religion

On matters of social justice, India’s politicians have always been ahead of the judiciary. Even though the Constitution “sacralized” caste in some ways (as John puts it) it didn’t stop Indian politicians from acknowledging and acting on concerns of representation and social justice, especially when it came to reservations. Pasmanda Muslim castes have been included in the list of “backward classes” for decades and it was only very recently that a concerted effort was made in Karnataka to try and limit the reach of reservation for backward classes on the basis of religion alone.

Where the question of caste and religion has always been fraught has perhaps been in the context of reservations for non-”Hindu” Dalits and whether they are “Scheduled Castes” for the purposes of the Constitution. (Interestingly enough this hasn’t been a concern for “Scheduled Tribes” and there was wide acceptance that their religious beliefs will have nothing to do with their constitutional status). While the category of “Scheduled Castes” only included Hindus at first, it now includes Buddhists and Sikhs (even though these religions would claim not to have any scriptural or ritual sanction for caste discrimination) and excludes Christians and Muslims (even though these religions would claim not to have any scriptural or ritual sanction for caste discrimination).

Yet, how do we make sense of Ambedkarites opposed to the inclusion of Dalit Muslims and Christians into the fold of Scheduled Castes? (Of course #NotAllAmbedkarites but the point remains) The simple, cynical way is to see this as a way to reduce “competition” for limited resources of state reserved for them. The complex question to ask is – have they accepted the sacralisation of caste as a “Hindu” problem as a given? A form of false consciousness that belies their lived reality? It poses a more thorny question – one that Khalid Anis Ansari asks in this article about Ambedkar’s agency and role in the passage of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950. John’s contribution in the fourth chapter of the book may be to ask us to interrogate the silences of the Constitution on matters of caste and religion in a deeper and richer way.

Conclusion

It would be trite to say that John’s arguments are thought provoking. This is a book which deserves deep engagement and critical reflection on the part of the reader. This is all the more important because there’s a risk of the Constitution itself being “sacralised” in a way. This is not peculiar to any one strand of Indian political discourse but must be rejected as a way of appreciating the Constitution.

The first part of this two-part blog series began with a reference to the inauguration of the Ram Mandir and what tells us about the future of a secular republic in India. The second part has been completed after the results of the 2024 general elections where the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party lost the Faizabad seat where the Ram Mandir is located. The former should not make us despair for the future of the Constitution as we know it, nor should the latter create complacency about the security of the secular republic. Engagement with the Constitution should not (ironically, in the context of John’s book) result in its sacralization.

Alok Prasanna Kumar graduated with a B.A. LL.B. (Hons) from the NALSAR University in 2008 and obtained the BCL from the University of Oxford in 2009. He is the Co-Founder and Lead, Vidhi Karnataka. His areas of research include judicial reforms, Constitutional law, urban development, and law and technology.

This Book Discussion was coordinated and edited by Archita Satish and posted by Baibhav Mishra from the technical team of the Student Editorial Board.