Blurb: The article argues for disability-inclusive prison reforms, emphasizing the right to reasonable accommodation and the right to dignity for incarcerated persons with disabilities in light of the dehumanizing treatment of Prof. Saibaba during his imprisonment.

Introduction

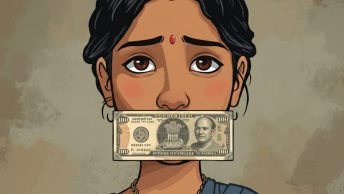

Confined to a wheelchair, Prof. G.N. Saibaba spent nearly a decade of his life in a windowless confinement with no living soul around and life clinging to his skin within the grim walls of Nagpur Central jail from May 2014 until his release in March 2024. With 90% physical impairment, he contracted COVID-19 twice and was diagnosed with multiple ailments during his carceral period. He testified for his ill health before the courts, however, he was repeatedly denied bail. Surviving in custody proved to be arduous for him as he was denied access to even basic necessities of personal care and hygiene and was forced to live in a horrendous environment. He breathed his last on October 12, only months after his acquittal in March.

The egregious tale of his incarceration merits our attention as it sheds light on the current prison system that denies assistance and specialized healthcare to prison inmates with disabilities. The author, through this article, seeks to examine the need to provide an accommodative system to prisoners with special needs in the carceral space with an emphasis on the right to accommodation and the right to dignity.

The piece is divided into two parts: Part I elaborates on the constitutional protections guaranteed to prisoners with disabilities. Part II begins by scrutinizing the legislative framework and argues that the needs of prisoners with disabilities are overlooked and not addressed comprehensively. Thereafter, the approaches of the United States and the United Kingdom vis-à-vis prisoners with disabilities are examined, making a case for statutory reforms in India to effectively implement constitutional safeguards.

Conceptualizing Disability Using the Social Lens

Theresia Degener rightly frames that overt reliance on the medical model of disability is an obstacle to the implementation of a human rights framework. Instead, a societal frame is required to understand disability. The social lens of disability emphasizes that disability is to be understood in correlation to those who meet societal standards of ability. The needs of individuals with disability are different from what is considered to be ‘normal’ which eventually puts a bar on their capabilities. This model underscores the interaction of people with disabilities within the structural setting which inhibits them from working at a par and positions them at a disadvantaged position than the rest.

The ‘social apartheid’ is sustained due to the existing environment that caters to the able-bodied while the ‘others’ are left to fend for themselves which gives rise to unequal power relations. This eventually trickles down to the prison system wherein people with disabilities are not provided with necessary adjustments which is exclusionary and amounts to discrimination. For instance, a person with physical impairments might struggle in a prison that lacks accommodative facilities such as ramps and accessible toilets. Drawing from Oliver’s work, the hurdles exist not due to the physical impairment but due to the societal interaction with the barriers.

The Right of Persons with Disabilities, 2016 (“RPwD”) defines “persons with disability” as an individual with “long term impairment” that, when interacting with societal barriers, hinders their “full and effective participation in society.” The RPwD’s approach marks a shift from the medical model under the 1995 PwD Act to the social model. However, this understanding is yet to permeate the carceral space, as the piece will demonstrate.

Before delving into the legislative response, the article shall emphasize the right to reasonable accommodation and the right to dignity.

The Right to Reasonable Accommodation

The right against discrimination includes the right to reasonable accommodation to ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity. It is a positive obligation on the state to remove barriers created by standard policies or practices and accommodate the needs of the differently abled. In Vikash Kumar v UPSC, the Apex Court affirmed that a key component of equality and non-discrimination is reasonable accommodation. Chandrachud, J. (as he was then), noted that the principle of reasonable accommodation is individualized whereby the needs of an individual are to be considered on a case-to-case basis. The obligation is immediate in nature and requires consultation with the concerned person to address the issue at hand.

The argument of ‘undue burden’ is often put forward to deny equal treatment to persons with disabilities, suggesting an onerous burden on institutions to make accommodations.

One of the prominent cases that dealt with the argument of ‘undue burden’ is Ranjit Kumar Rajak v SBI wherein the Bombay High Court discussed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (“CRPD”), to which India is a party, at lengths. The court noted that the CRPD can be read into Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, thus, casting a duty on the State to provide reasonable accommodation if the ‘burden hardship test’ is satisfied. The court expanded the test of undue burden as explored under ‘the Concept of Reasonable Accommodation in Selected National Disability Legislations’ prepared by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The paper depends on two factors- first, reasonability in circumstances, and, second, the proportionality test is to be employed to balance the right and burden, and the onus to prove an ‘unjustifiable burden’ rests on the defendant.

The court in Vikash Kuman v UPSC, though did not elaborate the ‘undue burden’ test, relied on General Comment No. 6 of CRPD Committee which develops the test of ‘undue burden’. The CPRD Committee noted that the evaluation of burden should be on a case-by-case basis, considering numerous factors, however, the accommodation should not impose additional costs on the persons with disabilities and will be considered ‘reasonable’ only if it is altered to “meet the requirements of persons with disabilities”. An instance of it can be when Saibaba, being an undertrial prisoner, needed to travel to courts, ‘reasonability’ requires travel to be accommodative to cater to his needs, and not to be extravagant.

Fredman argues that such accommodations are not to be seen as extraordinary burdens on the authorities but rather as necessary measures to uphold the dignity and rights of individuals with disabilities. Denying the adjustments based on institutional convenience perpetuates paternalism and exclusion from what the Constitution of India mandates which is fairness and justice for all. Being accommodative should not be construed as segregation but a step towards an inclusive framework in prisons.

The Right to Dignity

The right to personal care and hygiene is integral to the right to dignity and bodily integrity guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. During incarceration, the State takes away the liberty of the person, however, it has a duty to ensure the dignity of the person which includes providing them with adequate material conditions to live. Despite the guarantees of law, living conditions in prisons are extremely unsanitary, and basic amenities are often compromised, as stated in the Standing Committee Report.

Section 3 of RPwD obligates the government to ensure that persons with disabilities live with the right to dignity and equality. The statutory provision embodies the constitutional right enshrined under Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Constitution of India. In Inhumane Conditions in 1382 prisons, In Re, the court affirmed that the prisoners should be treated as humans and are entitled to all the basic human rights, including the right to dignity. A combined understanding underscores the duty of the State to provide prisoners with disabilities with accommodation to ensure their dignity and well-being.

In alignment with this, in Sunil Batra v Delhi Administration and Ors, the apex court rightly affirmed that the curtailment of rights should be in accordance with the Constitution and should satisfy the reasonableness test. As per the judgment, the core objective of sentencing is rehabilitation, and forsaking the aforesaid aims in favour of dehumanizing practices is counter-effective and goes against the spirit of Article 19. Additionally, torture in prisons, under the guise of security, is unconstitutional and unjustifiable.

It is worthwhile to mention that in addition to Saibaba, Stan Swamy, who was suffering from Parkison’s, was denied straw and sipper which were needed to access essential water during his time in prison. Denying specialized care to individuals with disabilities hinders their accessibility to essentials like sanitation and henceforth, is a direct denial of their right to dignity and amounts to torture.

Hence, in this part the constitutional protections bestowed upon prisoners with disabilities have been elucidated. In the second part of the article, an examination of the legislative approach in India would be carried out, alongside a cross-jurisdictional comparative analysis of the legislative frameworks of the USA and the UK.

q6bqk3