Summary: This piece by Tarun Natarajan analyzes the judgment of Supriyo@ Supriya Chakraborty & Anr v Union of India from an inheritance law perspective, while providing suggestions in order to foster marriage equality from the lens of the Special Marriage Act and the Hindu Succession Act.

Premise and Introduction

Recently, in Supriyo Chakroborty the Apex Court unanimously ruled that non-heteronormative unions could not be read into the provisions of the Special Marriage Act (hereinafter referred to as ‘SMA’). The court reasoned that the gender-neutral reading of the law this warranted fell outside the judiciary’s ambit. With the passing of this baton to the legislature, albeit unfortunate, comes opportunity- an opportunity to take one of many (legislative) routes to engage with marriage equality. One of these routes, lies in amending the SMA to reflect a gender-neutral notion of husband and wife. This would be the fastest course of action to enable marriage equality as opposed to drafting a new legislation. However, one of the biggest obstacles to this is the implications it would have on the diverse landscape of Indian inheritance laws.

When it comes to succession, both the petitioners in the case and scholars have suggested the application of Section 21A of the SMA, by extensively reasoning that a gender neutral, albeit mutatis mutandis application of the Hindu Succession Act (hereinafter referred to as ‘HSA’) is feasible.

The author welcomes this move and sees it as a stepping stone towards the judicial promise of equality for the queer community. However, there are a few situations where the application of the HSA (even in a gender-neutral manner) may not be viable, because of the heteronormative considerations with which the 1956 Act was drafted. This article will examine the absurdities created by these distinctions, considering the extant adoption framework. By using hypothetical scenarios, the author seeks to recommend minor changes to the HSA and SMA, so that the promise of marriage equality is truly fulfilled.

The child of de jure single parent in a same-sex male union

Presently India has two major laws which govern adoptions- the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956 (hereinafter referred to as ‘HAMA’) and the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (hereinafter referred to as ‘JJA’). Under sections 7 and 8 read with section 6(i) of the HAMA, both married couples and single males and females (individually) may adopt, provided they are Hindu. Similarly, under the JJA, pursuant to Rule 5(2) of the Adoption Regulations, 2022 (hereinafter referred to as ‘2022 Regulations’) either married couples, single males or females may adopt. Since extant marital laws in India do not recognise non-heteronormative couples, both gay and lesbian couples have been precluded from adopting as a couple. Moreover, even same-sex marriages recognised under foreign law have been barred from adopting by the Central Adoption Resource Authority (hereinafter referred to as ‘CARA’). However, queer individuals, notwithstanding their relationship status are presently allowed to adopt under the adoption framework.

In result, Indian queer persons have been forced to adopt children as individuals, not couples, and many queer Indians have taken this route. Moreover, a child cannot be simultaneously adopted by two persons under section 10(ii) of HAMA and Rule 10 of the 2022 Regulations. This legal nuance creates a situation where although a child may be raised by two or more parents de facto (in reality), they are only the child of only one parent de jure (under the law).

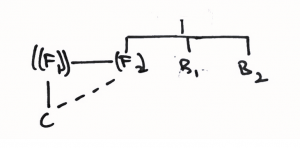

While this scenario does not seem to pose issues at the outset, it does so when the parent who is not legally recognised passes away, essentially issueless. For instance (Figure below), imagine a gay marriage between two Hindu males, F1 and F2, who have raised C, who was adopted solely by F1, and they have no other issue.

F1 predeceases F2. F2 has two brothers, B1 and B2. Since F2 has no other child, and is raising a child adopted by only F1, succession laws view him as issueless. When F2 passes away leaving no spouse or legal child, the law sees him as devoid of class I heirs. According to section 8 of the HSA, F2’s self-acquired property would devolve upon his brothers, B1 and B2 recognised under Entry II of Class II, to the exclusion of the child he had raised.

The child of a de jure single parent in a female same sex union

On the other hand, if the above situation was modified to describe a female same-sex union, oddly enough the very section that has been deemed patriarchal i.e., section 15(1)(b), comes to C’s rescue. Since F2 is legally issueless and predeceased by her wife, she has no heirs under section 15(1)(a). Pursuant to section 15(1)(b) her property would devolve upon her wife, F1’s heirs, i.e., C, who is F2’s child as well, although the law does not recognise their relationship as mother and child. Since C is F1’s child legally (vide adoption), C would receive both her mothers’ properties under Hindu intestate succession. Such stark incongruities between lesbian and gay couples ought to be corrected if marriage equality was to truly embody “equality.”

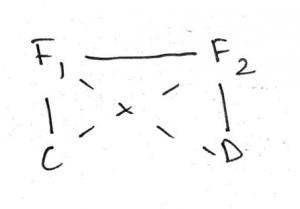

However, this does not immunise children of lesbian marriages from irregularities in their inheritance rights. For instance, in the above scenario, if F1 and F2, as two females, were to raise 2 children, F1 adopting the first child-C and F2 adopting the second child-D (Figure below); C would inherit F1’s property to their sibling D’s exclusion and D would inherit F2’s property to C’s exclusion. This creates disproportionately unequal inheritance for children of queer unions, antithetical to established principles of succession law.

Previously the lines between de facto and de jure occurrences have been blurred. For example, for the purposes of claims under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, relationships like marriage such as live-in relationships, have been treated the same as marriages. In X v. Principal Secretary, the SC equated a change in relationship status with a change in marital status as a ground to have an abortion within 24 weeks. Similarly succession laws must not restrict the rights of a child in a queer union only to inherit from one parent. Provisions that recognise inheritance from both parents who have raised the child (notwithstanding the legal recognition of parenthood) must be introduced in the strive for marriage equality.

These socio-legal issues are exacerbated by the bar against re-adoption under section 10(ii), HAMA and Rule 15, 2022 Regulations. Thereby even if queer couples can get married in the future, re-adoption of the child after marriage, as a couple, would be impossible. While laws recognising queer marriages, would automatically qualify them for adoption (since, presently, married couples under Rule 5 is not qualified by sexuality, rather marriage as a right is qualified by sexuality), amendments allowing for the re-adoption of their child, from one parent to the married couple would be essential.

Concluding thoughts

The diversity that Indian inheritance law is recognised by proves our nation to be an interesting case study to see how inheritance rights of queer families, if their equality in marriage is recognised, plays out. The potential application complimented with a gender-neutral interpretation of the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 to same-sex unions is one such case study. The marriage qualification for a couple to be able to adopt a child coupled with the fact that one member in a queer relationship may adopt, leaves the child of such a union capable of inheriting only from the parent who adopted them. However, the passing of the baton from the judiciary to the legislature means that minor amendments to the HSA and adoption laws can be made, in the form of provisos exclusively for same-sex unions. This would prove integral to ensuring the fulfilment of equality in marriage and equality of children of diverse familial units.

[Ed Note: This Article has been edited by Ajinkyaraj Pacharaney and published by Harshitha Adari from the Student Editorial Team.]