In Part I, I began by setting out the concept of federalism in brief. I then proceeded to explain the judgment in Lalta Prasad, focusing on the majority’s application of the innovative principle of federal balance. Now, in Part II I will provide arguments supporting the approach taken in this case.

“Weaker Party” and the Rule in Kesoram

The Supreme Court in Kesoram dealt with whether a royalty is a tax in the context of mines and minerals. It observed

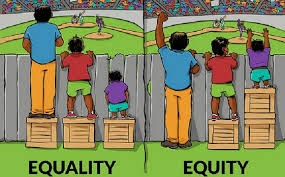

True, the Centre has been given more powers but the same is accompanied by certain additional responsibilities as well. The Constitution is an organic living document. Its outlook and expression as perceived and expressed by the interpreters of the Constitution must be dynamic and keep pace with the changing times. Though the basics and fundamentals of the Constitution remain unalterable, the interpretation of the flexible provisions of the Constitution can be accompanied by dynamism and lean, in case of conflict, in favour of the weaker or the one who is more needy. Several taxes are collected by the Centre and allocation of revenue is made to States from time to time. The Centre consuming the lion’s share of revenue has attracted good amount of criticism at the hands of the States and financial experts. The interpretation of Entries can afford to strike a balance, or at least try to remove imbalance, so far as it can. Any conscious whittling down of the powers of the State can be guarded against by the Courts. [Emphasis supplied]

While the Court acknowledged that the Constitution was drafted with an intent to ensure a strong Centre, it sought to ensure that such strength did not result in an infructuous or nominal federal setup. Accordingly, a rule was established that in case of conflict involving flexible provisions, the courts may favour the weaker party of the two – almost invariably the states. The purpose being, of course, to maintain the federal balance.

Reading the Constitution – A (Not So) Plain Task?

A general rule of statutory interpretation is the rule of plain reading – “When the words of a statute are clear, plain and unambiguous, i.e. they are reasonably susceptible to only one meaning, the courts are bound to give effect to that meaning regardless of consequences.” Consequently, in such cases as per this rule it is not open to the Courts to “adopt any other hypothetical construction on the ground that such construction is more consistent with the alleged object and policy of the Act.” As a general rule, it serves a necessary purpose insofar as it simplifies construction in most cases and places a reasonable restraint on judicial review. The concern is that where the legislature is clear, the Courts ought not look into the policy involved or the consequences thereof.

However, I would argue that this rule does not apply to most cases of Constitutional interpretation. This is due to the special nature of the Constitution, especially in the case of India, which sets it apart from ordinary legislation.

Firstly, a Constitution is intended to be an enduring instrument, designed to serve for a long time without frequent revision. As such, it must not only meet the needs of the day, but also meet those of the future. Even in India, with a history of frequent amendments, many provisions remain unamended, especially given the limited scope of amendment as per the Basic Structure doctrine.

Moreover, it contains a “framework of government” – its purpose is not to go into the niche particulars, but to lay down the mechanisms and fields of legislation, rights and ideals underpinning the government. The Supreme Court has observed that these ideals are expressed in general terms – “the intention of a Constitution is rather to outline principles than engrave details”. They form a “framework of concepts and concepts may change more than words themselves”. A question of constitutional interpretation must be resolved keeping in mind not just the words used in the impugned provisions, but more significantly the concepts underlying said provisions.

Perhaps most significant, the provisions in the Constitution are not supposed to be read in isolation. They are “necessarily related to, transforming and in turn transformed by, other provisions, words and phrases in the Constitution.” Hence, a Court has more freedom in the interpretation of a Constitution than in the interpretation of other laws.

Admittedly, in cases where the language is plain and specific, the Constitution has left no gap or abeyance, and the literal construction provides “no difficulty to the Constitutional scheme”, the rule of plain reading does have application. However, cases which actually arise are rarely so clear. Importantly, the rule ought not to have application where there is merely the appearance of a plain reading and a plain construction would in fact provide difficulty to the Constitutional scheme. In other words where it would be clear only in isolation and not when read with the rest of the Constitution, it must not be adopted.

The judgment in Lalta Prasad is an excellent example of this principle. On a cursory glance, Entry 52 may appear plain, especially given that the words read in by the majority are expressly provided in Entry 54 and absent in Entry 52. However, this appearance belies the impact that such a reading would have on the federal balance. Given this impact, it cannot be said that the plain reading causes no difficulty to the Constitutional scheme. Here, the principle of federal balance enters to rescue the Constitutional scheme from this difficulty. Innovative interpretation closes the loophole which is a natural consequence of the plain interpretation in this case – the possibility of the Union taking over, as discussed above, taking over industries as it pleased, leaving only those to the States which would be convenient for it. Hence, application of the rule of plain reading is untenable, and construction must be done keeping in mind, inter alia, the principle of federal balance.

Of course, derogation from the rule of plain reading must be done carefully and with grave appreciation of the consequences; it would be a great shame if with the intention of protecting the federalism, the Court’s actions itself shattered it. As in any matter involving the Constitution, such interpretation must involve careful reasoning and application of mind by the Court. The consequences of both the plain reading and the proposed reading must be carefully weighed, and even an otherwise concerning plain reading must be sustained if derogation through the latter reading causes greater harm to the federal setup.

Constitutional Interpretation – the Basic Structure Question

The Basic Structure doctrine lays down limitations on the power of Parliament to amend the Constitution. It was established in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, where the Supreme Court held that Parliament can amend any provision of the Constitution (including fundamental rights), so long as it does not alter, abrogate, or destroy the ‘basic structure’ or ‘essential features’ of the Constitution.

Ordinarily, the doctrine is applied in cases challenging specific constitutional amendments. However, notably in S.R. Bommai v. Union of India, it was applied in the context of dismissing state governments and establishing President’s Rule under Article 356. Particularly, the Supreme Court noted that secularism was one of the basic features of the Constitution, and hence, the Court observed that “the acts of a State Government which are calculated to subvert or sabotage secularism as enshrined in our Constitution, can lawfully be deemed to give rise to a situation in which the Government of the State cannot be carried on in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution.” Hence, it is clear that the basic structure doctrine is not limited to questions of validity of constitutional amendments. In this section, I argue that the doctrine has a role to play in questions of constitutional interpretation.

The argument is quite simple – a provision of the Constitution cannot be interpreted in a manner that it would be destructive of any of its basic features. In the present case, while both the majority and the dissent’s readings are certainly plausible, as has been explained in previous sections, the former seeks to carefully preserve the federal balance, while the latter has the potential to shatter it. While the dissenting opinion in ¶29 treats federalism as an important value, one “even more primordial than the [basic] structure”, considering it a value on which “the entire edifice of the Constitution itself” is built, it fails to consider the impact its proposed reading has on this value. It is humbly submitted that the significance of this oversight cannot be understated – it is quite crucial that when dealing with provisions impacting basic features, a basic rule be followed that an interpretation, to be good in law, must be in consonance with the basic structure of the Constitution. Hence, I argue that the dissenting reading cannot be sustained, for it would be in conflict with and may even be destructive of federalism, a basic feature of the Constitution.

In the final section, I will conclude this article, with a comment on the implications of Lalta Prasad on future cases.

Concluding Note – Implications

The case is a part of a succession of cases which mark a shift in the jurisprudence concerning federal balance under the Indian Constitution. It establishes a clear precedent for interpreting the Constitution keeping in mind the need to maintain the federal balance between the Union and the States, even if a plain reading may otherwise imply a different interpretation. While innovative, the decision remains rooted in firm theories of constitutional interpretation. Accordingly, future cases involving constitutional interpretation of provisions affecting the powers, duties and/or responsibilities of the Union and the States, must necessarily be adjudicated keeping in mind this conception of federal balance.

It is pertinent to note at this point that this case is not entirely a one-off decision, but is part of a succession of cases that have been resolved keeping federal balance in mind. The Mines and Minerals Case held that the States have a right to tax mines and minerals, subject only to express limitation through a law made by Parliament. In State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh the Court held that States have the power to create sub-classifications within the SC and ST categories. The key insight drawn from this judgement is the necessity of interpreting in line with federal balance, even where a plain reading would imply otherwise.

Prospectively, it may have a bearing on matters that come up before the Court, including pending cases. An illustrative example is that of Youth for Equality v. State of Bihar, a case challenging the validity of the caste-based survey presently being conducted by the Bihar government. The petitioners claim that the survey was an attempt by the Bihar government, given that ‘census’ falls under Entry 69 of List I. However, as was noted by the Patna High Court in its order, the state government cannot wait on their “haunches” while waiting for the Union government’s census to implement proactive measures in its services, especially with respect to Articles 15 and 16. While a restrictive reading of Entry 69 may limit the power of State governments to collect quantitative data on a large scale, applying federal balance to this issue in my view will result in allowing State governments such as Bihar to conduct caste-based surveys. A plain reading might imply that only the Union has the authority to collect demographic data on a large scale, as ‘census’ falls under the Union list. However, in order to maintain the federal balance, the States must be allowed to collect certain quantifiable data, which may be a condition precedent for them to establish certain State-specific reservation policies. Thus, while the conduct of a regular national census shall be the responsibility of the Union, in my view it would be appropriate to allow States to conduct surveys necessary for them to exercise their powers and implement policies accordingly, notwithstanding the fact that the Union government has now announced the conduct of a caste census as part of the regular census.

It is crucial that such matters of interpretation be resolved keeping in mind federal balance, in order to ensure the maintenance of the institution of federalism in the country. As legal professionals, especially those interested in the sphere of constitutional law, we have the capacity to anticipate similar conflicts coming up in the future. Indeed, the emergent tendency to take an approach centring federal balance may become one of the more notable developments in constitutional law of our times.

Jairaj Singh Basur is a second year B.A. LL.B (Hons.) student studying in the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru.

[Ed Note: This piece is edited by Hamza Khan and Published by Baibhav Mishra from LAOT blog.]

I enjoyed every paragraph. Thank you for this.

This helped clarify a lot of questions I had.

I’m definitely going to apply what I’ve learned here.

I love the clarity in your writing.

You’ve sparked my interest in this topic.

I enjoyed every paragraph. Thank you for this.

Üsküdar su kaçak tespiti Rothenberger cihazı sayesinde Üsküdar’daki evimdeki su kaçağını kırmadan tespit ettiler, çok memnun kaldım. https://everythingforyou36.com/uskudarda-su-kacagi-tespiti/

I like how you kept it informative without being too technical.

Akustik su kaçağı tespiti Teknolojik cihazlarla su kaçağı tespit ettiler, sonuç çok iyiydi. https://hideitalia.com/2023/07/05/uskudar-su-kacagi-tespiti-24/

Üsküdar su kaçağı bulma servisi Testo termal kamera ile su sızıntısı tespitini hızlıca yaptılar, Üsküdar’da bu hizmetten çok memnun kaldım. https://trilhasjuridicas.com/uskudar-su-kacagi-tespiti-2025/

You made some excellent points here. Well done!

I like how you presented both sides of the argument fairly.

I enjoyed your perspective on this topic. Looking forward to more content.

What I really liked is how easy this was to follow. Even for someone who’s not super tech-savvy, it made perfect sense.

Üsküdar su kaçağı tespiti 2025 Üsküdar’da su kaçağı sorunlarına kalıcı çözümler! Akıllı cihazlarla kaçağı kısa sürede tespit ediyor ve onarıyoruz. https://sedigital.in/uskudarda-su-kacagi-tespiti-nasil-yapilir/

Your tips are practical and easy to apply. Thanks a lot!

Your content never disappoints. Keep up the great work!

Your content always adds value to my day.

Thank you for being so generous with your knowledge.

This article came at the perfect time for me.

You’ve done a great job with this. I ended up learning something new without even realizing it—very smooth writing!

Great points, well supported by facts and logic.

I love how well-organized and detailed this post is.

You write with so much clarity and confidence. Impressive!

This was so insightful. I took notes while reading!

Your writing always inspires me to learn more.

Secesta, Türkiye’nin lider dijital çözüm sağlayıcısı olarak işletmelere özel SEO hizmetleri, yazılım geliştirme ve dijital pazarlama çözümleriyle fark yaratıyor. İstanbul merkezli bir ajans olan Secesta, arama motoru optimizasyonu (SEO) konusunda derin uzmanlığıyla markaların Google’da üst sıralarda yer almasını sağlıyor. Site içi SEO, teknik SEO, mobil uyumluluk ve hızlı yüklenen web siteleri geliştirme gibi konularda sektöre yön veren Secesta, aynı zamanda dönüşüm oranı yüksek reklam kampanyalarıyla ROI odaklı dijital pazarlama stratejileri sunuyor. Secesta’nın SEO hizmeti, sadece anahtar kelime odaklı değil; kullanıcı deneyimi, içerik kalitesi ve teknik altyapı gibi tüm yönleri kapsayan bütünsel bir yaklaşımı benimsiyor. ASP.NET Core, PHP ve WordPress teknolojilerinde uzman ekibiyle, performans odaklı web yazılımları geliştiren Secesta, her projeye özel SEO uyumlu kodlama ve içerik stratejileri sunarak uzun vadeli başarıya odaklanıyor. Google Ads ve Meta reklam yönetimi gibi dijital pazarlama alanlarında da %100 müşteri memnuniyetini hedefleyen Secesta, markaların dijital dünyadaki görünürlüğünü artırmak ve rekabet avantajı sağlamak için ideal bir iş ortağıdır. Eğer siz de dijitalde görünür olmak, SEO gücünüzü artırmak ve kalıcı başarılar elde etmek istiyorsanız, doğru yerdesiniz: Secesta ile dijitalde kazanın!