Federalism is one of the core aspects of the Indian polity, being the cornerstone of the administrative structure of the Indian State and integral to Indian politics in general. It is part of the basic structure of the Indian Constitution. Part of the scheme of federalism in India is the division of legislative subjects as described in Article 246 and the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution.

The Seventh Schedule is comprised of entries which each concern a particular legislative subject; these entries are divided into three lists, each of which read with Article 246 determine the legislative competence of the Union and the State governments. However, some of these entries overlap, and thus it becomes critical to interpret these entries in order to conclusively determine the legislative competence of the Union and the State governments.

In this article, I examine the idea of “federal balance” as discussed in State of Uttar Pradesh vs. Lalta Prasad Vaish (“Lalta Prasad”), otherwise referred to as the ‘Industrial Alcohol Case’. Through a discussion of this case, I aim to highlight the concept of federal balance as it serves as the rationale for the particular interpretation given for one of the aforementioned overlaps, in the judgement. The case marks a shift in such interpretations, and in this article, I aim to bring out the significance of this shift. Further, I aim to provide doctrinal argumentation supporting this shift.

Firstly, I will begin by briefly discussing some aspects of the case and its issues in order to provide some context and background to my analysis. Secondly, I will draw from academic discourse on federalism to highlight some key perspectives which provide the context in which the idea of federal balance becomes relevant. Thirdly, I will proceed to analyse the concept of “federal balance” as discussed in the judgement; specifically, I will highlight how the relevant constitutional provisions were interpreted in order to maintain federal balance. In the following sections, I will propose general arguments supporting the line that has been taken in this case. Hence, fourthly, I will analyse the “weaker party” rule established in State of West Bengal v. Kesoram Industries Ltd (“Kesoram”). Fifthly, I will argue that the rule of plain reading generally lacks application to constitutional interpretation. Sixthly, I will consider the application of the Basic Structure doctrine to questions of constitutional interpretation. Finally, I will then conclude my article by discussing potential implications of the judgement on other matters which may involve the concept of “federal balance,” as well as its impact on the field of constitutional law broadly.

Lalta Prasad – the Industrial Alcohol Case

In Lalta Prasad, a nine-judge Constitution Bench was constituted to determine the correctness of Synthetic and Chemicals Ltd. vs. State of Uttar Pradesh (“Synthetics [7J]”), with the key question being whether “intoxicating liquor” in Entry 8 of the State List (List II of the Seventh Schedule) only includes potable alcohol, i.e. alcoholic beverages, or also includes industrial alcohol, i.e. alcohol which is used in the production of other products.

The judgement notes three issues – Whether Entry 52 of List I of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution overrides Entry 8 of List II; whether the expression ‘intoxicating liquors’ in Entry 8 of List II of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution includes alcohol other than potable alcohol; and whether a notified order under Section 18G of the IDRA is necessary for Parliament to occupy the field under Entry 33 of List III of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution.

Entry 8 of List II deals with intoxicating liquors, including its “production, manufacture, possession, transport, purchase and sale.” Entry 52 of List I concerns industries whose control by the Union is declared by Parliament to be “expedient in the public interest.” Given that under the provisions of the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act, 1951, Alcohol is declared to be one such industry, whose control by the Union is expedient in the public interest; it becomes necessary to interpret the overlap between the two entries, particularly with respect to industrial alcohol.

Tensions in Scholarship: Academic Perspectives

With over seven decades having passed since the adoption and enforcement of the Constitution, there has developed extensive literature on the subject. In order to understand the import of the paradigm shift marked by Lalta Prasad, it becomes all the more crucial to highlight relevant academic perspectives.

Though the Seventh Schedule enumerates the distribution of legislative fields, there are certain areas which are “incoherent and ambiguous.” It has been noted that the distribution of legislative and executive powers did not produce neat mutually exclusive compartments because of innumerable overlaps in practice; in fact, State administrations function under the umbrella of central legislation and there are hardly any areas where some central legislation does not exist.

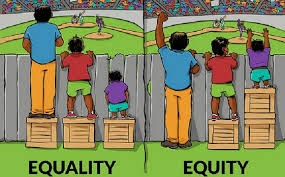

It has also been observed that the way in which regional autonomy is provided under the Indian scheme affords a certain flexibility, and is able to thereby avoid the rigidness to which federal models are often vulnerable. It is imperative that the interpretation of legislative entries be done keeping this flexibility in mind, ensuring that the federal balance of the Indian polity does not yield to a rigid and unyielding interpretation.

Interpreting Federal Balance: Judicial Approaches in Lalta Prasad

As the dissent notes, the use of a non-obstante clause in Article 246(1) (which grants the Union its legislative power) and that of a subjugation clause in Article 246(3) (the clause for the States’ power) makes the predominance of Parliament clear. The dissent’s interpretation of federal balance was on that ground limited to the division of legislative entries alone, with parliamentary supremacy holding in cases of conflict. Thus, the dissent concluded that “because of the unique manner in which Article 246 of the Constitution is worded…the balance…[tips] in favour of the Union in certain niche areas of legislation and governance.”

Per contra, the key insight that the majority highlights in ¶44 must be noted – that federal balance lies not on the “recognition” of Parliamentary predominance but on the “identification of the scope of such predominance.” In order to maintain the federal balance, this Parliamentary predominance is then limited only to cases where there is “irreconcilable direct conflict”, and not cases where there is merely an “overlap”, as there was in the instant case. Such overlapping entries must then be interpreted harmoniously, regardless of which list the entries are in, and parliamentary supremacy relied on only when such method of interpretation fails. To take an overbroad interpretation, as I respectfully submit the dissent does, would not merely tip the balance in favour of the Union. Rather, it would break the balance scale.

The concern in the present case stemmed from the lack of the phrase “to the extent to which” in Entry 52, unlike its parallel provision Entry 54. Entry 54 deals with the “regulation of mines and mineral development to the extent to which such regulation and development under the control of Union is declared by Parliament by law to be expedient in public interest.” The majority cited Mineral Area Development Authority v Steel Authority of India (“Mines and Minerals Case”), in which it was held that Parliament when making a law under the entry must “specify the extent to which the Parliamentary regulation is deemed expedient in the public interest.”

Despite the absence of the phrase in Entry 52, the majority in ¶¶60-65 read in a similar implied limitation, holding that the “legislative competence of the State Legislature is only denuded to the extent of the ‘control’ by the Union declared by the law of Parliament to be expedient in the public interest.” This was done in order to maintain federal balance – without this limitation, Parliament would have the power to by law declare any and all industries to be in the control of the Union. Thus, in this case, the Supreme Court refused to interpret a legislative entry through a plain reading, in order to maintain federal balance.

The significance of this interpretation cannot be understated – this is not a case where the provision is otherwise vague or uncertain, and thus where there would be a necessity to construct the provision harmoniously, while keeping in mind the intent of the legislature. The Court could have interpreted the provision literally, as it had done earlier in Synthetics [7J]. However, this would have allowed the Union to take over industries as it pleased, leaving only those to the States which would be convenient for it, without requiring such a move to be in the public interest. This would have had concerning implications – the federal setup in India is not merely a matter of administrative convenience, but a matter of division of powers between the Union and States such that India can be an effective and cohesive Union of States. In order to maintain this cohesion, a balance must be necessarily struck between the powers and duties of the Union and those of the States. Thus, interpreting the provision in the light of federal balance becomes a necessity, one that is relevant enough for the Court to go beyond a plain reading in interpreting provisions which affect the federal division of powers, and thus ultimately the federal balance. The power that Parliament would thus have, to take through a law under Entry 52 the control of not merely some niche areas but any and all industries in the nation, would substantially disrupt the federal balance between the Union and the States, and would not merely be, as the dissent for its part envisions, a small change affecting niche areas of governance.

Hence finally, the majority made its decision keeping these principles in mind, i.e. that overlapping entries must be reconciled harmoniously without regard to parliamentary supremacy, and that a declaration of control by the Union under Entry 52 must be limited to what is deemed by law to be in the public interest. It also noted the fact that Entry 52 is a general entry dealing with industry and Entry 8 is a special entry dealing with the particular industry of ‘intoxicating liquor’, and as per the principles of generalia specialibus non derogant a general entry may not make a special entry redundant by prevailing over it. Accordingly, the majority held that “Parliament does not have the legislative competence to enact a law taking control of the industry of intoxicating liquor under Entry 52 of List I.”

In Part II, I will argue for broader principles which support the innovative stance which has been taken in the judgment; I will also conclude my analysis with a discussion on the potential implications of the judgment in that part.

Jairaj Singh Basur is a second year B.A. LL.B (Hons.) student studying in the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru.

[Ed Note: This piece is edited by Hamza Khan and Published by Baibhav Mishra from LAOT blog.]

Toy Poodle, zarif görünümü ve zeki yapısıyla dünyanın en sevilen köpek ırklarından biridir. “Toy” kelimesi, bu cinsin boyutunu ifade eder; standart ve minyatür poodle’ların en küçüğüdür. Ortalama 24-28 cm yüksekliğe ve 2-4 kilogram ağırlığa sahiptir. Küçük yapısına rağmen oldukça enerjik, canlı ve sosyal bir karaktere sahiptir. İlk olarak Fransa’da popülerleşmiş olsa da, kökeni Almanya’ya dayanmaktadır. Av köpeği olarak yetiştirilen Poodle’lar, zamanla zarif görünümü nedeniyle aristokratlar arasında süs köpeği olarak da ilgi görmeye başlamıştır.

Zeka seviyesi oldukça yüksek olan Toy Poodle’lar, eğitime çok açıktır. Komutları hızlı öğrenirler ve genellikle pozitif pekiştirmeyle yapılan eğitimlerde üstün başarı gösterirler. Bu yönleriyle çocuklu aileler, yaşlı bireyler ya da ilk kez köpek sahibi olacak kişiler için uygun bir tercihtir. Aynı zamanda çeşitli köpek sporlarında da başarılı olurlar. Ev içinde sakin olsalar da, enerjilerini atabilmeleri için günlük yürüyüşler ve zihin açıcı aktiviteler gereklidir. Uzun süre yalnız bırakıldıklarında ise can sıkıntısından dolayı huzursuz olabilirler.

Bir arkadaşımın önerisiyle toy poodle ilanlarına sahipleniyorum.com üzerinden bakmaya başladım. Gördüğüm kadarıyla hem ilanlar güncel tutuluyor hem de iletişim kısmı oldukça kolay. Toy poodle gibi popüler bir ırkı güvenli bir şekilde sahiplenmek isteyenler için ideal bir platform.