Introduction

The recent observations of Justice B.R. Gavai in State of Punjab v Davinder Singh, with three other judges agreeing that the creamy layer (“CL”) needs to be excluded from SC/ST reservations, have sparked an age-old debate. While some view this as a misunderstanding of the nature of reservations and its goals, highlighting that such an exclusion may defeat the purpose of affirmative action, others find that the exclusion is necessary to ensure that the benefit of affirmative action reaches the most vulnerable among the SC/ST.

This article will attempt to understand the objectives of reservations in the Indian Constitution. It will then argue that instead of excluding the CL completely, a preferential model can be put in place for the non-creamy lawyer (“NCL”). Doing so would further the objectives of reservation.

The objectives of Affirmative Action

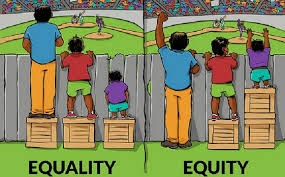

A reading of the Constituent Assembly debates and the Supreme Court decisions would show three justifications for reservation in India. First, the inadequate representation of the SC/ST communities as highlighted by Dr. Ambedkar and H.J. Khandekar. Second, promotion of economic interest of the backward communities, thereby alleviating their backwardness. This justification has been noted by the Supreme Court (“SC”) in multiple cases (here and here), where it held that Article 15(4) and Article 16(4) give effect to Article 46. Third, to achieve substantive equality; it is essential to recognize that individuals with access to resources will inherently perform better than those without. A merit-based system that fails to consider the varying circumstances of individuals cannot truly foster equality. Therefore, reservations serve as a protective measure, ensuring that those with limited resources are shielded from unqualified competition. This purpose of reservations, i.e., accounting for lack of access to resources has been eloquently highlighted by Justice Chinnappa Reddy in Vasanth Kumar.

The following sections shall examine whether a differential treatment of the creamy layer from the SC/ST would further these objectives or defeat them.

Preferential Treatment for the NCL Furthers Substantive Equality

Justice Chinnappa in Vasanth Kumar while arguing in favour of reservations asked,

“Is not a child of the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes or other backward classes who has been brought up in an atmosphere of penury, illiteracy and anti-culture, who is looked down upon by tradition and society, who has no books and magazines to read at home, no radio to listen, no T.V. to watch, no one to help him with his homework, who goes to the nearest local board school and college, whose parents are either illiterate or so ignorant and informed that he cannot even hope to seek their advice on any matter of importance… as meritorious as a higher scoring child who had access to the above?”

The same logic of ensuring substantive equality that operates behind affirmative action for SC/ST is operative behind protecting the NCL of the said groups from competing with the CL. A Dalit child belonging to a financially disadvantaged family would face the above hurdles as highlighted by Justice Chinnappa, while a Dalit child belonging to a well-off family may have had access to these resources. Therefore, pitting them in an open unqualified competition will inherently favour the latter, due to the absence of a level-playing field. After all, treating unequals equally is as much violative of Article 14 as treating equals unequally.

Preferential Treatment Addresses Backwardness More Effectively

It is frequently argued that the economic mobility or well-being of members of the SC/ST does not take away from the social stigma that the said groups face. Exclusion of the CL from reservations is thus said to be based on a flawed understanding of social discrimination.

While it was argued earlier that the SC/ST are a homogenous group, this understanding goes against the lived experiences which evidence the gradation of backwardness in the society. A study of intersectionality of experiences, makes clear the fact that marginalization and disadvantage have many axes. While a financially well-off Dalit may face disadvantage due to his caste identity, a financially disadvantaged Dalit suffers across two axes of marginalisation, i.e., class and caste.

Backwardness is multi-faceted; it demonstrates itself in different ways and every demonstration of discrimination has a distinct remedy. No form of affirmative action or welfare legislation in isolation can ensure complete elimination of the various forms of discriminations that an individual may face. A close look at Article 46 would be instructive in this regard. While the first part requires that the state promote the educational and economic interests of the backward communities, the second part obligates the state to protect them from social injustice and exploitation.

Ensuring economic well-being of individuals through access to public education and offices of public employment can offset a certain facet of discrimination. This is evident from the first part of Article 46. Remedying social injustice and protection from exploitation as given in the second part of the Article requires other remedies such as strict enforcement of the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act, sensitization of the civil society, etc. Thus, while an affluent member of the SC/ST community may still face social stigma, this cannot be addressed simply by offering public education or employment, which only elevate economic status. Instead, other measures must be implemented to reduce the social stigma that persists despite his affluence.

An argument in favour of preferential treatment for the NCL only needs to show that the NCL face an added level of backwardness, and therefore require special protection. This in no way suggests that the CL have become equal to the general classes and therefore, must be completely excluded from reservations.

Preferential Treatment Would not Compromise on Representation

A valid argument is made that the exclusion of creamy layer may lead to absence of representation of the SC/ST in public sphere and therefore, would defeat one of the main objectives of reservation, i.e., adequate representation. Therefore, if the CL are excluded, a situation may arise where there are not enough candidates from the NCL who meet the eligibility criteria, and hence the reserved seats remain vacant and are filled by candidates from the general category.

The solution for exclusion of CL leading to underrepresentation can be in the employment of a ‘preference model’ rather than the exclusion model in reserved seats. These different models of sub-classification were elaborately discussed by D.Y. Chandrachud in his opinion in State of Punjab v Davinder Singh.

The preference model can be briefly understood as a policy where a certain group is preferred for the seats, and in absence of sufficient eligible applicants from the reserved seats, the seats may be filled by the other group rather than complete exclusion of the latter. Using the preference model for NCL within the SC/ST category would ensure that, when enough eligible NCL applicants are available, they are prioritized over CL candidates. This approach effectively addresses the dual axes of marginalization they experience—both in terms of caste and economic status. However, in absence of sufficient applicants from the NCL who meet the eligibility criteria, the seats are filled by the CL of the SC/ST, rather than going to the general category. This would ensure that the exclusion of CL does not dilute the representation of the SC/ST as a group from the public sphere.

It has been argued that reserving seats in public education and employment for the CL within marginalized communities would create a trickle-down effect, ultimately benefiting the entire community. However, the preferential model seeks to directly benefit those within the SC/ST community who face compounded forms of marginalization, with seats prioritized for the NCL and, only in their absence, allocated to the CL. This approach ensures that opportunities go directly to those most disadvantaged, rather than relying on an indirect trickle-down effect. By prioritizing the NCL, the seats remain within the community and are allocated to those who need them most, without diverting them to the general category.

Conclusion

The system of reservations enshrined in the Indian Constitution serves three primary objectives. First, it ensures the representation of historically marginalized and underrepresented communities, addressing structural exclusion from public life. Second, reservations function as a remedial measure to promote the economic advancement of individuals from these communities. Finally, reservations aim to achieve substantive equality by recognizing and addressing existing inequalities through differential treatment, thereby fostering a more equitable social framework.

A preferential model for the NCL among the SC/ST community is based on an understanding of backwardness based on intersectionality of marginalization and the caste-class nexus. It would address backwardness more effectively, and further substantive equality, while not tinkering with the representation of the communities in question. Understanding reservations as a facet of equality, rather than an exception to it, rests on the principle that genuine equality requires recognizing and addressing unequal starting points. This concept of substantive equality provides a compelling basis for considering intra-community differences, such as financial means, to account for the varied challenges faced by individuals within the same community. By doing so, the reservations system would be able to accommodate diverse forms of disadvantage, acknowledging that economic disparities can compound other axes of marginalization within a single community.

Hamza Khan is a third-year student at NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad

[ Ed Note: This article was edited by Sukrut Khandekar and published by Baibhav Mishra from the Student Editorial Team. ]

rrne9n

8nd3m5