Summary: In this article, I explore how emotions such as fear and empathy underlie judicial opinions in Aishat Shifa v. The State of Karnataka using Sara Ahmed’s theory of “affective economies.” By contrasting Justice Gupta’s ‘feared secularism’ rooted in uniformity and control, with Justice Dhulia’s ‘empathetic dignity’ centred on autonomy and inclusion, I exhibit how constitutional interpretation is shaped by economies that define the emotional politics of Indian pluralism.

In this article, I explore how emotions such as fear and empathy underlie judicial opinions in Aishat Shifa v. The State of Karnataka using Sara Ahmed’s theory of “affective economies.” By contrasting Justice Gupta’s ‘feared secularism’ rooted in uniformity and control with Justice Dhulia’s “empathetic dignity” centred on autonomy and inclusion, I exhibit how constitutional interpretation is shaped by economies that define the emotional politics of Indian pluralism.

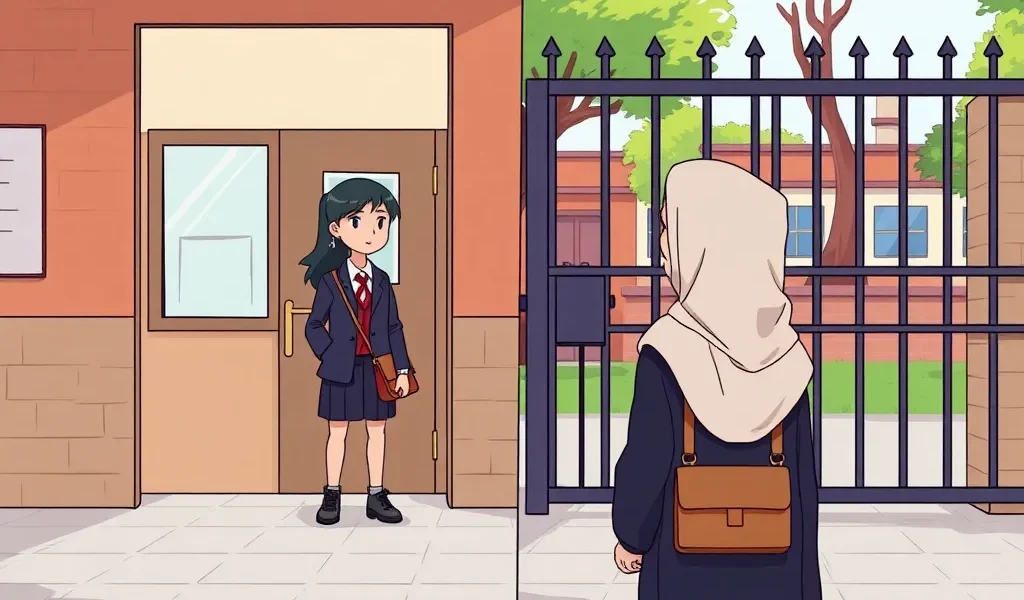

A society is never far from reacting in ways known to the public because an emotional turmoil garbed under the guise of rationality often guides the political environment of any state. As András Sajó puts it, emotions are not irrational interferences with reason but rather fundamental components embedded in the fabric of constitutional design, influencing how values are interpreted, lived, and potentially denied. The 2022 hijab ban case was one such controversy, fraught with a moment of public contestation that was played out in images of locked school gates, pleading hijab-clad students, and counter-protesters. The matter was, hence, called upon to adjudicate in Aishat Shifa v. The State of Karnataka, which, however, led to a divergence in judicial opinions. This presents a constitutional deadlock as a cross-section of warring emotional systems, which Sara Ahmed refers to as “ affective economies.” Through her theory, I aim to highlight how we can unveil the affective economies that shaped the judges’ interpretations upon which constitutional values are affirmed or undermined.

- The Emotional Life of the Law

Traditionally, law is seen as the antithesis of emotion, a rational bulwark against unruly passion. However, Sajó challenges this binary, arguing that emotions are public forces that help build constitutions, as these “constitutional sentiments” reflect a society’s moral feelings. Since law struggles to oppose the dominant public emotion, it often reflects the feelings of the most powerful groups in diverse societies, and even the “neutral” constitutional choices are not emotionless; they are deliberate choices based on emotions like the fear of cruelty or oppression, which is the very reason fundamental rights exist.

In Affective Economies, Ahmed posits that emotions circulate like capital, accumulating value and doing political work. They move between bodies, signs, and institutions, creating alignments that produce the very boundaries between a collective “us” and a pathologized “them.” In this economy, emotions are not free-floating; they are made to “stick” to certain objects, words, and bodies produced as an effect of their circulation. For instance, fear can be made to “stick” to the figure of the hijab-wearing student. Here, the object becomes the feeling or the emotion it is said to generate. This is often mobilized to solidify the in-group because the fear of the ‘other’ can become necessary in producing a feeling of love and solidarity within the imagined ‘we’ of the nation. Hence, there is an apparent display of two competing “affective emotions” at play.

- The Case that Divided the Nation at the School Gate

The controversy arose when a government pre-university college in Udupi, Karnataka, barred a group of Muslim students from attending classes while wearing the hijab. The matter escalated when a controversial Karnataka Government Order (G.O.) dated 5.2.2022 mandated a uniform for government schools and directed private schools to adopt uniforms decided by their management boards “in the interests of unity, equality and public order.” (204) The Karnataka High Court (the “HC”) in Aishat Shifa v. The State of Karnataka upheld this order on the premise that “wearing of hijab by Muslim women does not form a part of Essential Religious Practice (ERP) in Islamic faith” and “prescribing a school uniform is a reasonable restriction that is constitutionally permissible.” This led to several appeals challenging its legality before the Supreme Court (the “Court”), where it delivered a split verdict, with Justice Gupta upholding the ban and Justice Dhulia striking it down.

From the legal standpoint, Justice Gupta dismissed the appeals, basing his opinion on the same reasoning provided by the HC. He maintained that fundamental rights are not absolute, and the G.O. fostered uniformity and secularism. Contrarily, Justice Dhulia disagreed, arguing that forcing students to remove hijabs infringed upon their privacy and dignity, denying them access to secular education in violation of Articles 19(1)(a), 21, and 25(1). He emphasized that reasonable accommodation is essential for a mature, diverse society and questioned how wearing a hijab could pose a public order issue.

- The Clash of “Affective Economies”

There seems to be a clash between the two competing “affective economies” that led to the split verdict, which I will refer to as Justice Gupta’s feared secularism economy and Justice Dhulia’s empathetic dignity economy.

It is, hence, important to define fear and empathy in this context. Fear is defined as an expectant withdrawal produced by an “object’s approach,” it is the “anticipation of future hurt” that shrinks the body and restricts mobility into symbols of threat within the cultural politics of emotion. Conversely, empathy functions as a “wish feeling” that acts as a “towardness” that opens up bodies to others through an active engagement with differences.

While Justice Gupta’s opinion, though framed as legal formalism, is driven by an underlying fear about social fragmentation and a desire for homogeneity and discipline. He argues that a secular and fraternal environment requires “removing any religious differences” (153) so that students are treated alike. Visible religious markers such as the hijab risk creating a segmented society and disrupting the idealized unity of the school. His opinion is that headscarves would undermine the uniformity expected in public institutions such as schools, where “education is to be imparted homogeneously and equally.” (157) Uniforms, therefore, become the mechanism through which this homogeneity and fraternity are enforced.

An ideal student/citizen in Justice Gupta’s feared secularism economy is someone who erases their religious identity at the school gate to adopt the uniform identity mandated by the state. In his view, if a student is allowed to alter their uniform, then it would lose its meaning, emphasizing that deviation is a threat to the desired order and discipline. This is because school is a place for training citizens for future endeavours that require rules, and its defiance is the “antithesis of discipline.” (189) By mandating that students look alike, he seeks to ensure they will “feel alike, think alike and study together in a cohesive, cordial atmosphere.” (163) This produces a sense of collective unity by suppressing visible religious differences, shaping an us (secular, uniform students) versus them (students who assert religious symbols) divide.

Within this economy, the hijab becomes the “sticky object,” relating to negative affects. Through this, it is transformed from an item of personal clothing into a symbol of religious belief that came to be seen as an illegitimate intrusion into a secular place. This links the hijab to an act of religious assertion, which undermines uniformity, threatens fraternity, leads to social fragmentation, and consequently, weakens the nation. By this logic, a young girl’s headscarf is made to feel like an existential threat. By portraying the hijab as the “antithesis of secularism,” it is framed as an object of fear, which is perceived as endangering the very idea of the secular state. The legal jargon of “uniformity,” “secularism,” etc., thus functions to mask the fear, framing an act of exclusion as a rational and necessary defence of the national order.

Contrarily, Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia presents a direct counter-narrative with his explicit focus on the emotional harm of the ban. His judgment is grounded in empathy for the girl and the values of dignity, privacy, autonomy, and choice. He expresses concern over the challenges already faced by a girl child in reaching her school and how denying education simply due to a hijab ‘attacks her dignity’ and ‘denies her education’ (262). This is an act of judicial empathy, asking the law to feel with the citizen who experiences its force by shifting the focus from the state’s anxieties to the student’s lived realities. By invoking reasonable accommodation and emphasizing the Constitution as a “document of Trust” (264) for minorities, he points out that these are rooted in a desire for a more inclusive, tolerant society that respects differences, rather than erases them.

The ideal society in his empathetic dignity economy is one where individuals can express their identity and faith without sacrificing their access to fundamental rights like education. This is because the strength of a plural society lies in cultural assimilation that accommodates diversity, not destroys it. He opines that the idea of fraternity does not mean enforcing homogeneity, but rather fostering mutual understanding and tolerance. Fundamental rights such as dignity and privacy are inherent to every individual and cannot be made conditional upon entering a public institution like a school because the fear is not about diversity but about the risk of the state marginalizing religions and cultures.

By doing so, Justice Dhulia is working to unstick the hijab from fear and attach it to positive, constitutionally cherished affects. It is no longer a symbol of disruption but of choice, conscience, belief, and expression. He makes the hijab “stick” with emotions of liberal democracy, reframing it as a symbol of aspiration and access by calling it a “ticket to education.” This links the hijab not to the threat of sectarianism but to the national promise of girls’ education and empowerment, fusing it with feelings of hope and progress.

By invoking Dr Ambedkar’s view of fraternity as the essential emotional glue for liberty and equality and Sardar Patel’s plea for the majority to “think about what the minorities feel,” (264) he frames fraternity not as an outcome of homogeneity. Instead, he presents it as an active cultivation of the practice of engaging with differences empathetically. He views the nation in its pluralistic sense, where the society finds its strength in its diversity. Historical judicial framings of fraternity as a “hierarchical brotherhood” of “elder brothers” assisting “weaker children” needing “crutches” represent a patronising model of majoritarian concession that stands in stark contrast to Justice Dhulia’s vision of fraternity as an emotional glue that requires an active engagement with difference. Through his framework, he seeks to reassure the minorities that their dignity is a paramount constitutional concern.

- Beyond the School Gate: The Emotional Politics of Indian Pluralism

In this case, both judges relied on established constitutional principles and precedents, yet their interpretations diverged because of different “constitutional sentiments” and the affective economies they implicitly embraced.

In my opinion, Justice Dhulia’s economy is more apt in a diverse nation like India that aims to promote plurality. This view is firmly grounded in Puttaswamy v. Union of India as well, which affirmed that fraternity is tied to celebrating differences, holding that “individual dignity and privacy are inextricably linked in a pattern woven out of a thread of diversity into the fabric of a plural culture.” To foster fraternity, constitutional morality is needed, so conscious efforts are made to adhere to the constitutional principles, such as to protect minorities from majoritarian impulses, especially when the ingrained social instincts pull in another direction. Since suppressing minority voices and expressions will sprout the seeds of hostility in a nation, it attacks the dignity upon which fraternity is built, leading to rifts it purports to prevent. Thus, while privacy “enables individuals to preserve their beliefs, thoughts, expressions against societal demands of homogeneity,” protection of dignity serves as the emotional glue for the social fabric because “it is the core which unites the fundamental rights,” fostering a climate of security and belonging for minorities.

This case illustrates how legal interpretations, even of fundamental constitutional principles, are shaped by underlying, often unacknowledged emotions. Here, the hijab became the site of the struggle, a “sticky object” onto which the nation’s fears about pluralism and its aspirations for dignity were projected. The judicial deadlock is not a sign of legal failure but a reflection of a nation with opposing affective economies. Hence, a truly just constitutionalism must be judged not solely by its logic but also by the kind of feelings it wishes to foster in all its citizens.

Ed Note: This piece was edited by Saloni Maheshwari and published by Tamanna Yadav from the student editorial board.

Author Bio: “Natalie Smriti Bilung is a third-year law student at the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru. She has a keen interest in space, corporate and constitutional law, alongside a deep appreciation for history, literature and cultural studies.”

They can be reached at

- Insta: natsung20.04

- LinkedIn: Natalie Smriti Bilung