INTRODUCTION

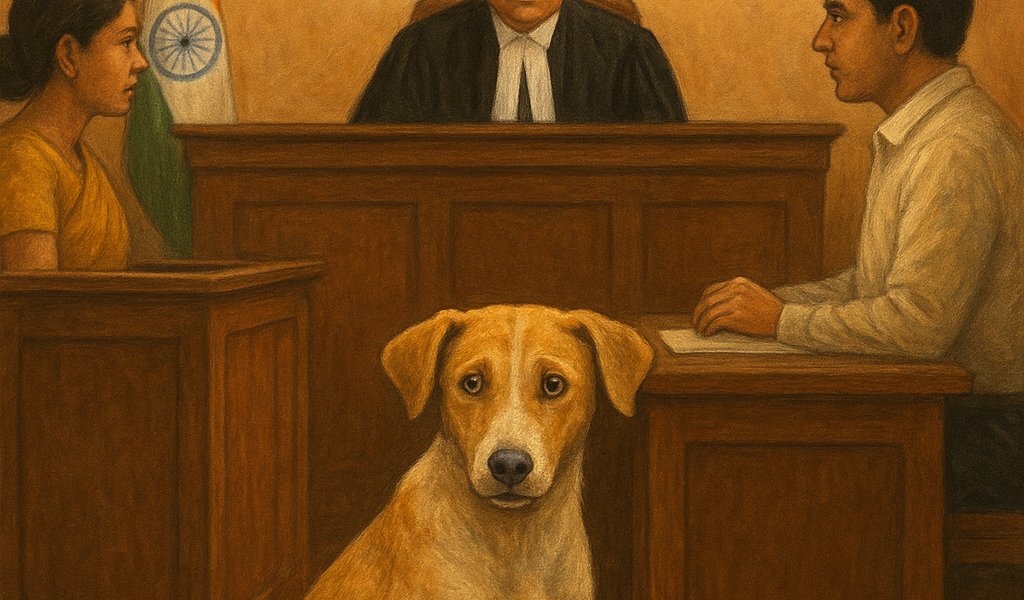

The order of the Division Bench of the Supreme Court of India, on August 11, 2025, to relocate all stray dogs from the streets to animal shelters certainly not only displays an unwillingness to be informed and an ignorance of practical realities, but it more so presents a deeper, more entrenched anomaly in the Indian legal system – laws, made by humans, inevitably reflect human priorities. Such a system presupposes a legal fiction (though the system itself does not acknowledge it to be so) that humans are able, rational, and can reason for other beings. From this presumption flows the self-appointed role of “protector” with an unquestioned position of domination over other sentients.

Critics may rightly argue that sufficient legislative protections are afforded to animals. Such reasoning, however, is not sympathetic to the lived interactions of animals with the system. For one, it is conceived and built on human necessities (rights, duties, obligations, and other relations are conceptually and theoretically human-aligning), and animals are forced to fit in this one-size-fits-all model designed for another species. Moreover, animal welfare laws seem to be a pitiful bargain for animals, rather than a framework for their welfare. The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960, is superficial protection, as experimentation for the advancement of new discoveries of physiological knowledge or knowledge to combat disease is not unlawful (notice how an “animal” law has human priorities). Similarly, the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, which shallowly purports to safeguard wildlife, is rooted in conserving species for ecological balance, tourism, and environmental security (again, preserving resources for human priorities).

While the order of the three-judge Bench of the Supreme Court, dated August 22, 2025, presents a more balanced approach, it certainly suffers from inadequacies of its own. Much has been said in criticism of the first order. In this article, I attempt to evaluate and rewrite the Supreme Court’s orders more equitably.

ANALYSING THE ORDER OF THE DIVISION BENCH

The Division Bench’s order reflects a judicial philosophy where human safety overrides animal interests. This is emblematic of a top-down approach in which the voices from the other side, including those of animal rights activists, community feeders, veterinarians, and, by implication, animals themselves, are categorically dismissed without being meaningfully considered. The very origin of the order exposes this bias. The Supreme Court took suo moto cognizance of a newspaper article; nobody complained to them about any dog bites. Yet, human interests were quickly elevated to the level of constitutional priorities, and public health was considered the prime concern of the hour. The Supreme Court, in doing so, treads a peculiar path that needs necessarily to be highlighted. On the one hand, it summarily dismisses holistic solutions already present in law (sterilisation policies under the Animal Birth Control Rules, 2023) in favour of a blanket relocation mandate. On the other hand, it signifies that public health means only ‘human’ public health, thereby making humans the sole legal subject of the matter. Had the Supreme Court considered dogs as legal subjects along with their human counterparts, it would have recognised the shared interests of both subjects, i.e., the health, autonomy and movement of dogs along with the health and safety of human beings. Shifting the goalpost from human public health to the shared interest of both parties would naturally have altered the trajectory of the order significantly.

When the premise of the Division Bench’s order is based on a self-conceived superiority complex, the consequential justice that follows is bound to display similar tendencies. The Supreme Court defines justice as capable of being delivered in human spaces, like the courtroom, shelters and municipal zones. Had the Supreme Court broadened the scope of space for justice, it would necessarily have explored alternate habitat-informed solutions and cohabitation strategies. This would include shared community spaces and public community feeding zones. Such a solution would be equitable and practically possible.

Equally troubling is the process by which the Division Bench’s order was reached. The Division Bench, in less than two weeks, issued sweeping directions for compliance by the municipal authorities. These directions were backed by a threat of penal action. Such a compressed timeline and punitive framework are a direct result of a lack of dialogue before the directions were made. What should have happened is that the Division Bench should have allowed a deliberative, inclusive and dialogic process, engaging animal rights activists, community feeders, veterinarians and other important stakeholders such as the municipal authorities. Varied perspectives would perhaps in my opinion, have changed the direction of the order significantly.

ANALYSING THE ORDER OF THE THREE-JUDGE BENCH

The order of the three-judge Bench dramatically moved the narrative to a more equitable, inclusive solution by staying the previous order. This was an obvious outcome, considering the already-existing legislative policy in place, in the form of the Animal Birth Control Rules, 2023. I suspect, however, that the mounting public pressure had quite to do with this marked shift as well.

While the order was a welcome step, the language of the order does not indicate a shift in the underlying attitude of the Supreme Court. Humans continue to be the prime legal subjects, and human interests are the prime legal objective sought to be achieved. I have three pertinent observations to be pointed out in the order that underscore its ongoing inadequacy in achieving genuine justice for all stakeholders.

Firstly, the three-judge Bench broadens the scope for justice delivery, beyond courtrooms and shelters to municipal feeding zones. In doing so, the Supreme Court recognises that animal welfare cannot be restricted to legal or custodial spaces. However, these spaces are still human-designed and human-controlled. True justice would include monitored public feeding areas and parks, respecting the natural movement and needs of stray dogs. While the designated feeding zones represent a more holistic solution, it is still a top-down intervention and is not habitat-informed.

Secondly, the three-judge Bench orders that each individual dog lover and each NGO that has approached the Court shall deposit a sum of Rs 25,000/- and Rs 2,00,000/-, respectively. This absurd directive is deeply problematic. By monetising compassion, the Supreme Court confuses the line between mere private intervention and a civic contribution, grounded in constitutional and statutory obligations. Not only does this directive disproportionately burden low and middle-income communities, which have traditionally been consistent caregivers, but it also shifts the responsibility of animal welfare onto private individuals instead of municipalities and state authorities, where it properly belongs.

The most troubling observation by the three-judge Bench is its reference to those who care for and feed stray dogs as “animal lovers”. This is questionable on several levels. It effectively trivialises the role of an entire section of legitimate stakeholders, i.e., animal caregivers and feeders, to a matter of personal preference and affection. Law has traditionally been wary of framing obligations and rights around mere affection, and to categorise caretakers as “lovers” reinforces the idea that their engagement is optional.

Legally speaking, such language is improper as it undermines the normative force of constitutional and statutory protections for animals. Animal welfare in India is not just a matter of love or preference, but stems from constitutional mandates under Articles 21, 48A, and 51A(g) of the Constitution, and statutory obligations under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960, and the Animal Birth Control Rules, 2023. Such language is also imprecise as it reinforces hierarchy, where human health is framed in the language of rights and public safety, but animal interests are relegated to simply love. Such an asymmetry makes it easy to dismiss non-human claims.

CONCLUSION

Both orders of the Supreme Court reflect possibilities and limitations of our present legal imagination. The initial order is paternalistic and reflects a human-centred jurisprudence where the law arrogates to itself the authority to decide for other species, without acknowledging their agency. The latter order, while more balanced and holistic, still falls short on many levels. When the Supreme Court is unable to recognise the rights, agency and autonomy of stray dogs as equal considerations to human health in the matter, it reproduces the very hierarchies it is set to dismantle.

It bears stating here that the Supreme Court can only function within the system it is in. Therefore, there is a need for a shift in statutory principles and judicial reasoning to reframe our laws, procedures, and spaces to be accommodating of non-human stakeholders. This involves broadening our legal imagination and shifting to a more inclusive justice system. Only then can we move from a jurisprudence of domination to one of coexistence. In essence, the law, while continuing to be spoken through human voices, must be capable of listening across species.

[Ed Note: This piece was edited by Harshitha Adari and published by Vedang Chouhan from the Student Editorial Team.]