Introduction

Indian jurisprudence has historically distinguished the legal profession from purely commercial enterprises, holding it to a higher standard of public service and social justice. It has been differentiated from trade and commerce in the context of the constitutional mandate under Article 39A. This differentiation was emphasised by the Supreme Court (“SC”) in D.K. Gandhi PS v. M. Mathias, wherein the legal profession was identified as sui generis and thus exempted from the Consumer Protection Act, 2019.

This distinction contextualises the traditionally protectionist stance of the Indian government when it comes to legal liberalisation. The controversy over permitting foreign legal practice in India evolved through judicial pronouncements beginning with Lawyers Collective v. Bar Council of India in 2009, which prohibited foreign firms from setting up liaison offices or practising in India unless they were compliant with the Advocates Act, 1961 (“AA”).

In 2018, the SC clarified in Bar Council of India v. A.K. Balaji that “practice of law” includes both litigious and non-litigious work, and only lawyers registered with the Bar Council of India (“BCI”) could offer legal services. A narrow exception for foreign lawyers was created, permitting casual and non-recurring fly-in, fly-out (“FIFO”) trips to give advisory services on foreign laws. Nevertheless, they remained barred from the actual practice of law.

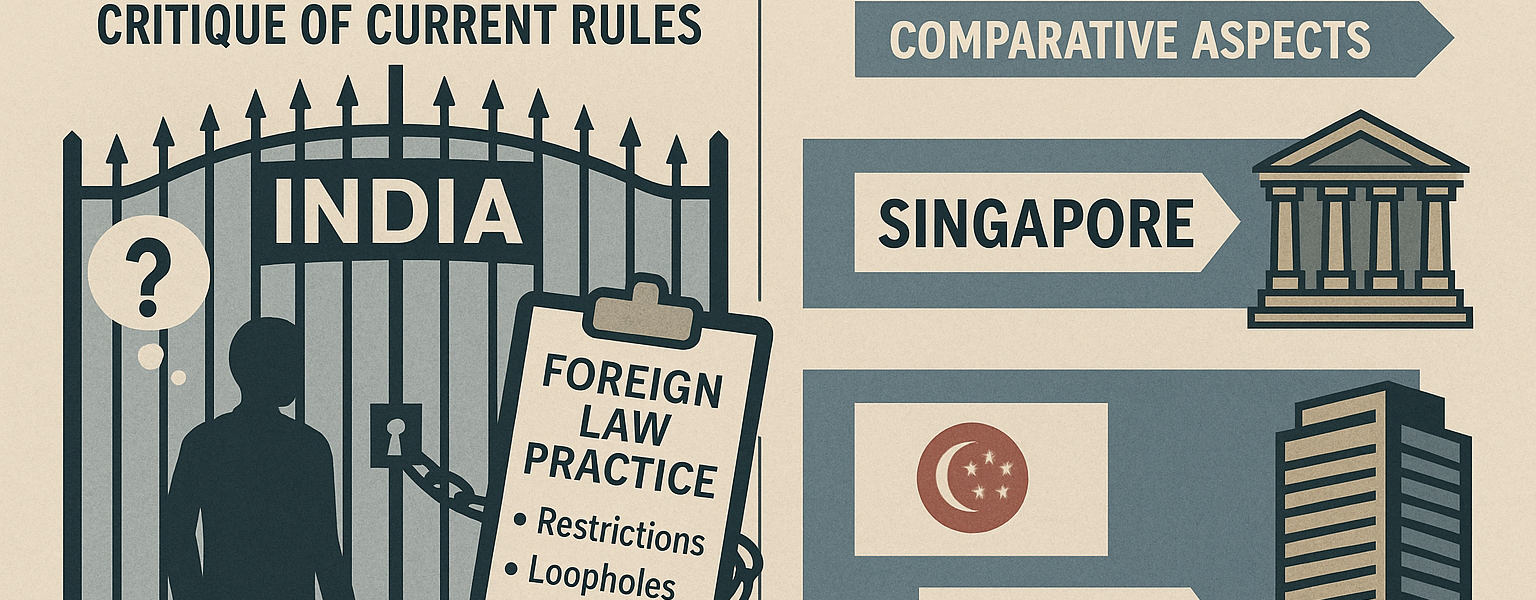

Recognition of growing cross-border markets and the potential benefits of legal liberalisation led to the notification of the Rules for Registration and Regulation of Foreign Lawyers and Foreign Law Firms in India, 2022 (“2022 Rules”) marking the first time that an official framework was put in place in this regard. In May 2025, the BCI amended and enforced its 2022 Rules to allow foreign law firms and lawyers to practice in India, aiming to modernise India’s legal sector. However, despite the progressive intent, loopholes and grey areas persist.

In this blog, we will critically analyse the new rules, identify key gaps, and draw comparative insights from the liberalisation models of Singapore & Japan, in order to propose a sustainable path to a modern and equitable legal landscape in India.

An Overview of the New Rules

The revised BCI regulations introduce substantial modifications. Along with an expanded definition of foreign lawyers, a new category of “Indian-Foreign Law Firms” has been created, permitting an Indian entity to practice Indian and foreign law, but only under prescribed and strict dual eligibility and registration provisions. Indian lawyers dually registered as foreign lawyers maintain their right to litigate under the AA as per Rule 2(iv)(b). However, they will need to follow BCI regulations in both instances.

In March 2023, the BCI gazetted the 2022 Rules, which had allowed foreign lawyers to visit for a maximum of 60 days annually on a FIFO basis without liability being explicitly provided. However, the 2025 amendment brings a six-point compliance system that allows FIFO visits without the requirement of registration. It strictly limits their role to an advisory capacity on foreign law, and requires them to duly provide information regarding the nature of work, legal areas involved, client details and jurisdictions. Moreover, they are barred from establishing offices or maintaining a prolonged presence. It clarifies the calculation of the 60-day period, which is to be calculated from the first day of their arrival, regardless of breaks. Additionally, it also gives BCI adjudicatory powers along with the capability to extend its ethical rules to FIFO engagements, unless explicitly exempted.

Together, these amendments mark a pivotal step towards liberalising India’s legal profession. However, a deeper analysis reveals concerns regarding the viability of this framework.

Legal Lacunae and Grey Areas

A core element of the new rules is the Doctrine of Reciprocity, which stipulates that foreign firms and lawyers will only be given the right to practice law in India if Indian lawyers are given similar rights in foreign jurisdictions. Although it appears to be a fair principle in theory, it remains largely undefined and non-transparent in practice. A good example of reciprocity can be the arrangement between Hong Kong and the UK, where, under the Qualified Lawyer Transfer Scheme Regulations, 2011 (“QLTS”), lawyers qualified in these jurisdictions are only allowed to practice English Law if they pass the QLTS assessments. Conversely, lawyers in England must pass the Overseas Lawyer Transfer Exam to practice in the Hong Kong Courts.

However, the 2025 Rules do not put in place such a clear, structured mechanism. There is no list of reciprocal countries, no criterion for what would qualify as “reciprocal,” and no independent method to verify the veracity of reciprocity claims. India’s underdeveloped stance on reciprocity and the absence of a uniform and fixed method for evaluating claims could hinder opportunities for Indian lawyers willing to undertake cross-border work.

Additionally, there is a need to reinforce the BCI Rules with amendments to the Advocates Act itself in order to eliminate statutory hurdles and insulate them from legal challenges later down the line. Section 24, read with Section 29 of the AA, restricts the right to practice law in India to Indian citizens, contradicting the progressive intent of the 2025 Rules and making them vulnerable to litigious proceedings.

Without clear legislative backing, they may meet the same fate as the RBI’s delegated permissions allowing foreign lawyers to liaison in India, which were struck down in Lawyer’s Collective because they lacked legislative support. Another pertinent example is the enactment of the Limited Liability Partnership Act, 2008 (“LLP Act”), which allowed foreign individuals and entities to form LLPs with Indian firms and establish a place of business in India. Though the act appeared to provide preliminary avenues for liberalisation by allowing foreign firms to work as LLPs, this was not made possible because the AA had not been amended.

Considering India’s low ranking in the 2024 Service Trade Restrictiveness Index (“STRI”) for “Legal Services,” despite policy-level attempts to liberalise the legal sector, it is evident that without legislative reforms and amendments into the AA, attempts to allow foreign firms and lawyers to operate in India through secondary rules would have only a minimal impact.

A key problem in the current framework is the uneven regulatory burden imposed on Indian lawyers. Rule 36 of the BCI Rules does not allow Indian advocates to advertise and solicit cases, restricting how they may market their services. This is based on the rationale clarified by Justice Krishna Iyer in Bar Council of Maharashtra v. MV Dabholkar, where he opined that lawyers are prohibited from advertising in order to preserve the legal profession’s sanctity and nobility.

However, this conception is rather outdated in the context of the contemporary globalised legal market and creates an imbalance by placing Indian firms at a competitive disadvantage. By comparison, foreign lawyers and firms are free to market and advertise their services at home and abroad as they fit. They may also undertake branding exercises in jurisdictions where it is permitted.

For example, in the UK, the Solicitors Regulatory Authority (“SRA”), responsible for governing the conduct of solicitors and law firms, in Rule 8.6-8.11 of the SRA Code of Conduct, permits registered lawyers to advertise and promote their services. Such advertisements must be compliant with strict ethical standards, like being accurate and not misleading. Singapore, too, has a comparable, but more elaborate framework in the form of the Legal Profession (Publicity) Rules.

When studies such as Hazard, Pearce, and Hodes (1983) have already refuted the notion that allowing lawyers to advertise can damage sanctity of the profession, and the parent legal system (the UK) from where we originally borrowed these ideals has since evolved to permit the same, there is no need for Indian jurisprudence to stick to these anachronistic lines of reasoning as has been argued in an earlier piece on the LAOT Blog by Yash Dahiya.

In addition, Section 11(2) of the Companies Act, 1956 restricts Indian law firms to have a maximum of 20 partners, unlike their foreign counterparts, who can have unlimited partners. Indian sole practitioners also have to deal with financial hurdles as they lack access to financial assistance from banks. Concerns also arise in regards to the broad regulatory powers enjoyed by the BCI, and in the absence of an alternative independent body to check FIFO engagements, investigate complaints, or evaluate the scope of foreign law practice, transparency is compromised.

The existence of these glaring lacunae casts a shadow over the intended benefits of the revised rules. Understanding where we fall short is only the first step. With legal liberalisation now firmly on the table, it is essential to ask: what can we borrow, and what must we avoid? In the next part, we move beyond India to examine how leading global legal hubs have approached similar challenges and what their experiences can teach us.

Ed Note: This post was edited by Hamza Khan and published by Baibhav Mishra from the Student Editorial Team.

Very informative

Good job