{Ed Note : In this piece, our Senior Analyst Shanthan Reddy analyses the recent Myanmar coup vis-a-vis the country’s questionable democratic status.}

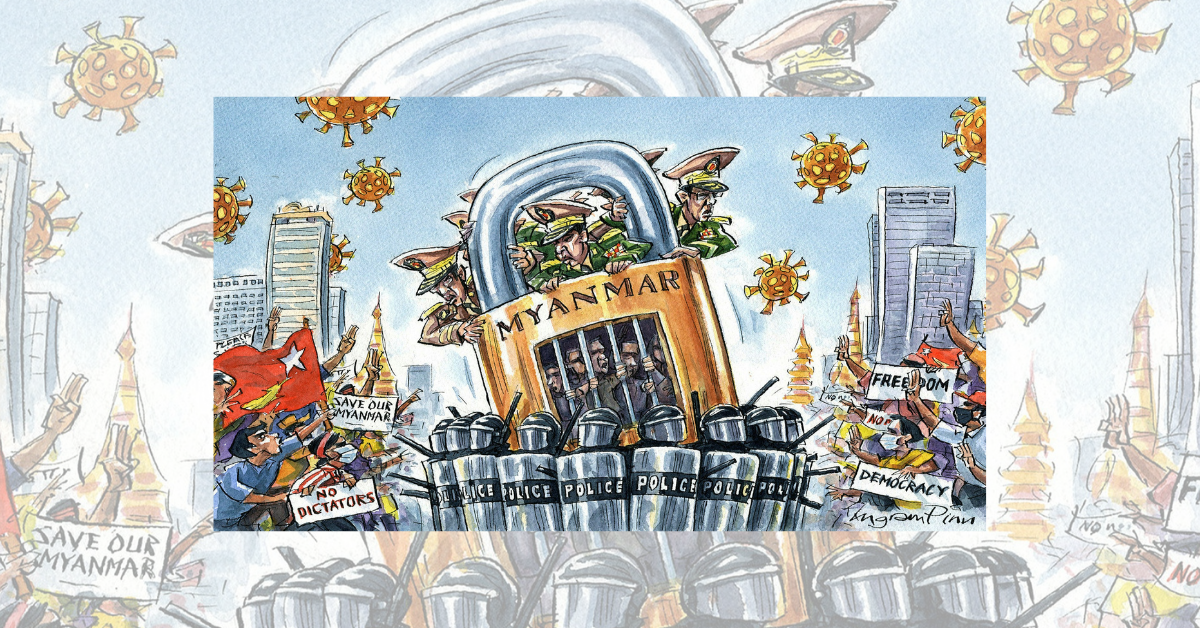

On February 1st 2021, the Myanmar military had detained Ann Sang Suu Kyi and other senior leaders of the National League for Democracy (NLD) and declared a state of emergency in the country.’ In conducting the coup, the military had followed its general modus operandi – taking control of the government, detaining and putting under house arrest all senior leaders of the government, and finally invoking the constitution to justify its action. According to the military, the takeover was because of the ‘alleged’ voter fraud in the November 2020 elections. The fact that the military repeatedly levied the allegation despite providing no evidence and contrary views being expressed by various other authorities indicates that the military had ‘manufactured’ a crisis to take control over the country.

Military coups and indirect military rule are a common place in the history of independent Myanmar. However, the current coup is unique as it has taken place in the backdrop of a democratic transition. Thus, it becomes important to analyse as to whether or not Myanmar was really on the path of ‘democratic transition’. Part I briefly lays down the role of the military in Myanmar’s history and in its transition to a democracy. Part II lays down a rough framework for analysis the state of ‘democracy’ in a country. Part III applies this framework to the situation of Myanmar.

I. Military in Myanmar – A Deeply Entrenched Institution

A peek into the Myanmar’s post-independence history shows that the military has been the country’s primary political institution. From 1962 onwards, the military held a stronghold over the country and controlled every aspect of public life. It owned schools and hospitals, and controlled large business enterprises. The military was entrenched into the public life of Myanmar and hence, was very influential. This ‘protracted’ military rule is key to understanding the various social, political and economic developments in Myanmar.

The military rule in Myanmar was not uprooted by a civil movement. The democratic transition since 2010 has been on the Military’s own accord. It can be argued that 1988 and 2007 movements might have created pressure on the military regime. However, they were not big enough or organised enough to threaten the military rule.[i] The democratic transition also cannot also be attributed to international pressure.[ii] Thus, the transition to a democratic state was ‘imposed’ by the military. The question of why military allowed for such a transitions is beyond the scope of this blog-post. However, it is important to note that through such a transition, the military did not intend to completely be away from political authority. It wanted to retain political authority to ensure that: i) its economic and social interest are protected and ii) state security and stability, two of its primary commitments, were protected.[iii] This explains why the Myanmar constitution and its provisions vest large discretionary powers on the military even in presence of an elected parliament.

Another reason why the transition can be termed as ‘imposed’ is because of the lack of legitimacy in the process of constitution making and its adoption. The constitution was drafted by a convention which was boycotted by the NLD and thus, there was no ‘opposition’ to the military in drafting the constitution. The referendum regarding the 2008 constitution was held at a time when Myanmar was facing its worst natural disaster and millions of citizens were dying. Further, Amnesty International had also expressed concern over the draft constitutions lack of emphasis on human rights and the conferring of wide powers on the military. Lastly, the lack of public consultation while drafting the constitution only adds to its illegitimacy. Thus, the 2008 constitution, as claimed by Professor Bruce Ackerman, “made no effort to hide the military’s continuing claim to hegemony—offering the democratic movement a subordinate role in politics”.[iv]

II. Quintessential Democratic Elements

Should the 2021 Myanmar coup be considered as a surprise? While a coup in any democratic state shall be considered a surprise, answering this question requires engagement with the issue of whether Myanmar can be considered to be a democracy.

A democracy, in its essence, should help in establishing a government which is representative of the will of the people, and is accountable to them. Elections, which are free, fair and periodic, are a means to achieve these objectives of representation and accountability. According to scholars such as Adam Przeworski, holding such elections in itself is enough to establish a democracy. However, others argue against such ‘minimalistic’ notions of democracy.[v] Professor Terry Karl calls this as the ‘fallacy of electoralism’, which is supported by Professor Larry Diamond. Professor Larry argues that despite their being electoral contestation, situations maybe present wherein significant areas of decision making powers are beyond the control of elected officials. Thus, the expression of the will of the people should be manifested in actual governance and decision making. The same has also been argued by Robert Dahl. Vesting of control over government decisions on elected officials and the actual exercise of ‘constitutional powers’ by such elected officials are two of the minimal procedural requirements that he prescribes must be a part of any democracy.[vi] The rationale is that if those elected by the people do not yield power, they will be in no position to truly represent or defend the interests of the people who elected them. Instead, they will act as instruments to create a ‘façade’ of democracy.

Thus in determining whether or not Myanmar is a democracy, these three criterion are taken into consideration – 1) Representation of the people’s will in governing bodies. 2) Conduction of election which are free, fair and periodic in nature. 3) Effective governance and decision making powers in hands of the elected officials.

III. Myanmar – A Namesake democracy ?

Myanmar fails to fulfil the first criterion. The basic element that separates a democratic and authoritarian rule is the fact that a democracy involves peoples’ representatives too hold power and represent in governing bodies. The accountability aspect of those in power comes through this aspect of the democracy. In Myanmar, the military commander-in-chief has unilateral power to name ¼ members of each house of the legislature. As these leaders are not elected, they do not have any incentive to be accountable to the people, and thus, are free to act against their interests. Further, the military also has guaranteed control over key ministries.

The fulfilment of the second criteria can be correctly assessed only over a period of time. This is because free and fair elections should also be ‘periodic’ in nature. Since democracy and elections started to make an entry post 2010, any analysis on the basis of ‘electoral’ aspect of democracy may be short-sighted and too narrow in its nature. The first election was held in 2011. The NLD considered the conditional constitutional gesture a sham and boycotted the elections, maintaining its revolutionary stance.[vii]. Thus in 2011, there was no effective choice as the military backed Union Solidarity and Development Party was the sole remaining party. First signs of effective electoral competition were only seen in 2015, when the NLD had participated in the elections and swept them. The same result was repeated in the 2020 elections. However, owing to the coup, the electoral result could not be effectuated.

Of more importance to our discussion is the third criterion, as failure on this front would further point that despite having electoral democracy, the same did not result in effective transition of decision and policy making powers. Between 2015-2020, Myanmar had a democratically elected government in place. However, this democratically elected government did not have full decision making powers, Nor did it have power to change policies or governing structures on its own accord. Under the 2008 constitution, 25% of the seats in the parliament were mandatorily reserved for the military officials. Any constitutional amendment would require more than 75% of votes, thus effectively allowing the military to veto any change which either threatens its position or is acting against its interests. For example, in March 2020, the civilian government tabled an amendment to the constitution which would have reduced the number of the seats for the military in the parliament. However, the military using its indirect ‘veto’ quashed the proposed amendment. Further, the military also sets and spends its budget on its own accord without any interference from the civilian government. Further, the economic liberalization started in the 1990ss has shifted economic power away from the state to various military owned crony companies. Scholars argue that as a result of such liberalization, the democratically elected government has little political authority over economic development of the country.

To aggravate matters, the constitution also rests wide-ranging powers on the military to control the country when the national solidarity or sovereignty is being threatened. ‘National solidarity’ and ‘national sovereignty’ are vague terms and thus, provide the military to operationalise its powers under the constitution on its whims and wishes, like it did so in the recent coup.

The above analysis shows that the imposed transition to democracy did not lead to a democratic state. It rather institutionalized a hybrid (semi authoritarian) form of regime where military interests trump substantive democratic values.[viii] If, democratic transition didn’t lead to a democratic state, why was the world in a hurry to label Myanmar as one? This question becomes important to answer because a lot of sanctions on Myanmar were lifted based on this promise of democratic transition. According to Than Myint-U, the reason might be the fact that such a labelling reaffirmed the western world that the world was moving in the direction of liberal values.

Conclusion

The above analysis shows that Myanmar was under a semi-authoritarian rule, with the constitution and other political institutions still vesting wide powers on unelected military officials. In such a situation, a coup is not a surprise. Rather, it is an event long-due. The keys to return to an autocratic military regime were placed in the hands of the military via the powers vested in it by the constitution. In 2021, the military chose to use the keys.

The failure of Myanmar’s democratic transition calls for a closer examination of any such transitional claims in the future. A constitution is the foundational document which determines the path that a country could take. However, as the main aim of Myanmar’s constitution was to institutionalize military power, the document failed to establish and entrench core democratic values in the country. Thus, any future transition to a democracy in Myanmar should begin with the rewriting of the current constitution. Such an exercise should be free from military influence and should include the participation of the larger civil society. Only then can it be ensured that the constitution is an embodiment of ‘national interests’ and not ‘military interests’.

[i] Zoltan Barany, How Armies Respond to Revolutions and Why, Princeton University Press (2016), 98-100.

[ii] Kristian Stokke & Soe Myint Aung, Transition to democracy or Hybrid regime? The dynamics and outcomes of democratization in Myanmar,32 The European Journal of Development Research (2020), 279.

[iii] Id at 283-284.

[iv] Bruce Ackerman, Revolutionary Constitutions, Harvard University Press (2019), 288.

[v] Carl Henrik, Measuring effective democracy, 31(2) International Political Science Review (2010), 111.

[vi] Philippe C. Schmitter & Terry Lynn Karl, What democracy is and is not,3 Journal of Democracy (1991), 81.

[vii] Supra note 5 at 289.

[viii] Supra note 3 at 294.

Shanthan Reddy is a 4th Year old student at NALSAR University of Law. He is interested in Criminal and Constitutional laws.

The author wants to thank Vishal Rakecha for his help in improving this piece.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me. https://www.binance.info/join?ref=P9L9FQKY