In this piece, the author argues that the deceased deserve a right to dignity and cautions against the dangers of AI-driven digital resurrections, which could reduce the dead to mere commodities. To illustrate this point, the author creates a digital persona using publicly available data, demonstrating that these digital resurrections result in pseudo-personalities that violate the deceased’s dignity.

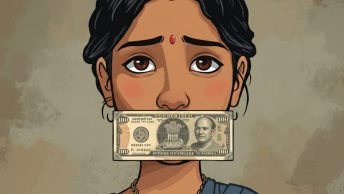

Digital Resurrection as a Violation of the Dead’s Dignity

Part I established the dead’s right to dignity, advocating for digital dignity in contemporary times. This part illustrates how digital resurrection infringes such a right.

Thanabots operate similarly to other chatbots, but their training data is strictly limited to the personal information of the deceased. Thus, the first step in the resurrection process involves uploading this personal data. Various scholars have argued that this data should be treated as property, applying concepts such as ownership, bailment, and transfer. Following this reasoning, the personal data being uploaded is owned by the deceased. Since the property rights of the dead are well-established, the living cannot utilise the deceased’s property against their wishes. It will be violative of their dignity.

Additionally, treating data as property would extend the application of Section 315 of BNS, 2023, to personal data. This means that any unauthorized use of the deceased’s data for personal purposes will be considered illegal. Thus, the living cannot use the deceased’s data without obtaining prior consent.

One could argue that the deceased’s successors, as the rightful owners of the deceased’s personal data, should be permitted to use it for resurrection. If ownership of property and intellectual assets can be transferred posthumously, then by analogy, personal data should also be subject to similar succession. In this sense, the act of passing down personal data inherently includes the possibility of its use, making succession functionally equivalent to the deceased granting consent. If the deceased had intended to prohibit such use, they would have placed explicit legal restrictions. Therefore, unless such limitations exist, the successors’ rights over personal data extend to decisions about its application, including resurrection. However, such a resurrection would still violate the dignity of the deceased in its second step.

The second step involves assessing the similarity between the digital clone and the data uploaded. This process requires making the clone as personalised as the data uploaded. Nevertheless, this level of personalisation can never fully capture a human’s true personality for two primary reasons.

First, thanabots are constrained by the data available. The living can only access limited information about the deceased, which means that any resurrection will inevitably lack an accurate representation of the person’s identity. This raises ethical concerns, as the resurrection may not reflect the deceased’s true personality. It also grants the living the power to shape the deceased’s identity according to their preferences. The selective nature of data collection allows them to shape the resurrection by choosing specific characteristics or memories they prefer. This selective recreation fundamentally distorts the authentic personality of the deceased, resulting in a false narrative. Such a misrepresentation also infringes upon Kant’s principle, which asserts that humans should not be treated merely as means to an end. Ultimately, the living would be creating the resurrection for their selfish purposes, altering the deceased’s social identity. This act, therefore, violates the dignity of the deceased.

Additionally, resurrection, in its current form, can be viewed as a type of deepfake. Deepfakes are digitally manipulated content created using artificial intelligence to fabricate representations of an individual’s face, voice, or both, often without their consent. This concept parallels digital resurrection, albeit it extends the manipulation to even the identity of the deceased (not limited to bodily manipulation but extends to the social identity). Even the steps followed in the resurrection are similar to those employed in creating deepfakes. Thus, arguments against deepfakes can also be applied to digital resurrection. Ruiter hints at this, arguing that a person’s social identity is closely linked to their bodily experience. Any violation of this social identity also constitutes a violation of their body. Since this social identity persists even after a person’s death, digital resurrection infringes upon this identity.

This violation can be supported by empirical evidence. Iwasaki’s research demonstrates that there is significant public resistance to non-consensual resurrections, with 58% of participants expressing disapproval. Even when consent is obtained, 40% of participants considered digital resurrection to be socially unacceptable. This indicates a widespread acknowledgment that such resurrection violates the autonomy and dignity of the deceased.

The second reason is that thanabots, and chatbots in general, are not creative. They excel at recognising patterns but struggle to generate original ideas. Instead, they produce text by predicting the next word based on probabilities derived from millions of previously uploaded phrases in their system. At best, they can rearrange data to create text that appears creative, which is actually a form of pseudo-creativity.

Moreover, thanabots lack other human traits such as empathy, adaptability, and decision-making skills. Without incorporating these human traits, the resurrection can never be personalised enough. This raises a profound question: If thanabots are not personalised, who is the living individual really conversing with? Is it the deceased’s personality or is it the chatbot giving pseudo-personalised responses generated by rearranging previously stored data?

If the latter is the case, every other resurrection could appear strikingly similar. What may seem personalized at first glance is likely to follow the same logic and structure, with only minor variations. This highlights the limitations of thanabots in creating genuinely unique and personalised interactions.

A Practical Experiment on Thanabots

This sub-section presents a practical experiment that demonstrates how attempts at digital resurrection remain fundamentally pseudo-personalised. Using OpenAI’s GPT-4o,[1] it explores two digital resurrections, Rit and Nit. Both are created from fabricated personal details. The objective is to assess whether thanabots can generate distinct responses reflective of their respective fictional personas. Despite the datasets being intentionally different, the results starkly highlight the inherent shortcomings of this technology.

Both Rit and Nit were asked the same question: “What should I do to keep pushing forward, even when things get tough?” While the generated responses appeared personalised and varied, they ultimately followed the same structure and tone. The advice centred around common themes such as sharing experiences, breaking challenges into smaller parts, seeking support from friends, and anchoring oneself in passions. While Rit references coding and guitar-playing, and Nit focuses on sketching and art, these elements merely reflect the input details. The overarching themes of finding joy, seeking support, and keeping goals in mind, were nearly identical, revealing the pseudo-personalised nature of the interactions. This challenges the core promise of thanabots to provide meaningful personalisation. Instead of mirroring the uniqueness of the deceased, these AI-driven tools simply rearrange the provided data.

One might argue that the results of the experiment were influenced by the limited nature of the fabricated datasets. If sufficient data is put, the resurrection could potentially be more personalised. However, as demonstrated, this will always be a challenge in resurrections. The living will only have limited data about the deceased, meaning that the answers generated will be based solely on that information. Furthermore, if there is no data available on the specific question asked, a generic answer will be produced, resulting in a lack of even pseudo-personalisation. This illustrates that digital clones can only reshuffle existing data and cannot provide creative responses. Thus, it cannot be personalised enough.

Conclusion

Having established that digital resurrection violates the dignity of the deceased, it can be concluded that it should not be allowed without their prior consent. Even if they don’t explicitly deny such resurrection, they should have a right to be forgotten.

One possible solution could be expanding the scope of Article 17 of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). It provides the right to be forgotten, which, if extended beyond death, could provide a legal basis for protecting individuals from unauthorised digital resurrection. Similarly, the United States’ Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA) allows designated heirs to access and manage a deceased person’s digital assets, but it also places limitations on unauthorised use (Section 8), offering a potential model for balancing data succession and dignity.

[1] Due to financial constraints and because many of the thanabots use Gpt-4o or some version of it as its base (see here and here), Gpt-4o is used.

The author is a law student at the National Law School of India Unviersity, Bangalore.

Ed. Note: This piece was edited by Hamza Khan and posted by Abhishek Sanjay from the Student Editorial Board.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge. This added a lot of value to my day.

You always deliver high-quality information. Thanks again!

I like how you presented both sides of the argument fairly.

I simply could not go away your web site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard info a person supply on your guests Is going to be back incessantly to investigate crosscheck new posts

I appreciate the depth and clarity of this post.

Thanks for addressing this topic—it’s so important.

What a helpful and well-structured post. Thanks a lot!

Your blog is a testament to your dedication to your craft. Your commitment to excellence is evident in every aspect of your writing. Thank you for being such a positive influence in the online community.

This topic really needed to be talked about. Thank you.

I like how you kept it informative without being too technical.

I just could not depart your web site prior to suggesting that I really loved the usual info an individual supply in your visitors Is gonna be back regularly to check up on new posts

This was easy to follow, even for someone new like me.

I’ll be sharing this with a few friends.

I learned something new today. Appreciate your work!

Your blog is a treasure trove of valuable insights and thought-provoking commentary. Your dedication to your craft is evident in every word you write. Keep up the fantastic work!

Keep educating and inspiring others with posts like this.

I do believe all the ideas youve presented for your post They are really convincing and will certainly work Nonetheless the posts are too short for novices May just you please lengthen them a little from subsequent time Thanks for the post

What i do not understood is in truth how you are not actually a lot more smartlyliked than you may be now You are very intelligent You realize therefore significantly in the case of this topic produced me individually imagine it from numerous numerous angles Its like men and women dont seem to be fascinated until it is one thing to do with Woman gaga Your own stuffs nice All the time care for it up

I was suggested this web site by my cousin Im not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my trouble You are incredible Thanks

Hi my family member I want to say that this post is awesome nice written and come with approximately all significant infos I would like to peer extra posts like this

Your articles never fail to captivate me. Each one is a testament to your expertise and dedication to your craft. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with the world.

Wow superb blog layout How long have you been blogging for you make blogging look easy The overall look of your site is magnificent as well as the content

Excellent blog here Also your website loads up very fast What web host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Your writing has a way of making even the most complex topics accessible and engaging. I’m constantly impressed by your ability to distill complicated concepts into easy-to-understand language.

Somebody essentially help to make significantly articles Id state This is the first time I frequented your web page and up to now I surprised with the research you made to make this actual post incredible Fantastic job

Efeler’de yaşayan biri olarak, gündemi yakalamak gerçekten önemli. https://haberinolsunaydin.com/ adresinde bölgeyle ilgili haberler çok hızlı güncelleniyor. İlçemizdeki ulaşım, belediye projeleri ve sosyal etkinlikler hakkında ilk elden bilgi alabiliyorum. Bu yüzden siteyi sık sık takip ediyorum.

Your blog has quickly become one of my favorites. Your writing is both insightful and thought-provoking, and I always come away from your posts feeling inspired. Keep up the phenomenal work!

you are truly a just right webmaster The site loading speed is incredible It kind of feels that youre doing any distinctive trick In addition The contents are masterwork you have done a great activity in this matter

Your writing has a way of resonating with me on a deep level. I appreciate the honesty and authenticity you bring to every post. Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

Your writing has a way of resonating with me on a deep level. It’s clear that you put a lot of thought and effort into each piece, and it certainly doesn’t go unnoticed.

hiI like your writing so much share we be in contact more approximately your article on AOL I need a specialist in this area to resolve my problem Maybe that is you Looking ahead to see you