–Guest post by Dhruva Gandhi, IV Year student, National Law School of India University, Bangalore

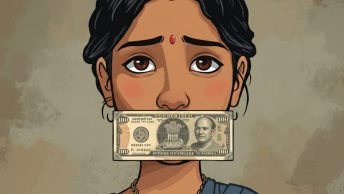

The introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) is widely hailed as an important taxation law reform in India. This reform measure seeks to subsume the multiplicity of taxes prevalent at both the Central as well as the State level, namely, excise duty, central sales tax, service tax and value added tax, into one uniform tax, that is, the GST.[1] To this end, the Constitution (One Hundred and First) Amendment Act, 2016, (‘the Amendment’) was enacted and subsequently, the necessary legislations have been passed by the House of the People.

However, these legislative measures were preceded by considerable negotiations between the Central Government and the State Governments. An important issue in these negotiations was the loss of revenue in the immediate future for the State Governments on account of the introduction of the GST. In fact, negotiations came to be stalled for a length of time because of this issue.[2] Finally, to convince the State Governments and to secure their consent to the introduction of GST, the Central Government promised to compensate the States for the loss of revenue for a period of five years. It was proposed that this compensation would be collected by levying an additional cess on taxpayers.[3] To lend sanctity to this promise, it was even made part of the Amendment.[4] Subsequently, the House of the People has also passed a statute dealing with compensation.[5]

In this write-up, it is contended that this promise and the consequent statute could potentially be unconstitutional.

The promise to pay compensation is contained in Section 18 of the the Amendment. It says,

“Parliament shall, by law, on the recommendation of the Goods and Services Tax Council, provide for compensation to the States for loss of revenue arising on account of implementation of the goods and services tax for a period of five years.”[6]

Although it is contained in a Constitution Amendment Act, this provision does not make any modifications to the Constitution. No provision is added to or repealed from the Constitution. As a consequence of the provision being enacted, the Constitution does not stand amended. Thus, it is only a provision of ordinary law. Evidently, this is a peculiar scenario- a provision of ordinary law is contained in a Constitution Amendment Act. This could also probably be the first instance when this has happened. Naturally then, a question that arises for consideration is whether this is permissible. Can an ordinary law be enacted by means of a Constitution Amendment Act?

The power to amend the Constitution- a constituent power- is vested in Parliament under Article 368 of the Constitution.[7] Article 368 also lays down the procedure to amend the Constitution. An amendment to the Constitution can be initiated only by the introduction of a Bill for that purpose in either House of Parliament and by passage of that Bill by each House, by a majority of the total membership of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting. Once it is passed by each House, it is to be sent to the President for his assent and the President is bound to give his assent to the Bill.[8] In case of amendments such as those contemplated for GST (amendments to the Part dealing with Relations between the Union and the States and to Lists distributing legislative powers between them), the Bill must also be ratified by one half of the States before it is sent to the President for his assent.[9] Nowhere does Article 368 contemplate the power to make an ordinary law.[10]

The power to make an ordinary law is vested in Parliament by Article 245 of the Constitution.[11] Article 246 (read with Lists I and III of the Seventh Schedule) deals with the subject matters over which Parliament may make laws.[12] The procedure to make these laws is contemplated in Articles 107, 108, 109 and 111 of the Constitution.[13] Article 107 says that a Bill other than a Money Bill and a Financial Bill may originate in either House of Parliament[14] and shall be said to have been passed by Parliament only when it is approved by both the Houses.[15] In case a Bill is rejected by the other House after having been passed by one House or both the Houses are not able to agree on the amendments proposed to the Bill, a Joint Session of Parliament may be called for by the President to deliberate and to vote on the Bill.[16] Once the Bill has been approved by both Houses or has been approved in a Joint Session, it is to be sent to the President for his assent. The President may either assent to the Bill or withhold his assent and send the Bill back to Parliament for reconsideration.[17]

In case of a Money Bill, there is a different procedure. This type of Bill can only originate in the House of the People and only needs to be approved by that House. The Council of States has a limited role when it comes to Money Bills in that it may only suggest amendments and it is for the other House to decide whether or not to accept those amendments.[18] Moreover, in case of a Money Bill, the President does not have the power to withhold his assent and to send the Bill back to the House of the People for reconsideration.[19]

Therefore, what follows is that both the power as well as the procedure contemplated for a Constitution Amendment Act is distinct from that envisaged for an ordinary law, irrespective of whether the law originates as a Money Bill or a Non-Money Bill. While the power to amend the Constitution- a constituent power- stems from Article 368, that to pass an ordinary law flows from Articles 245 and 246.[20] When it comes to the procedure, there are at least four aspects in which they differ.

One is that there is no concept of a Joint Session of Parliament in case the two Houses differ on the passage of a Constitution Amendment. It must be approved by both the Houses. Two is that the President is bound to give his assent in case of a Constitution Amendment Bill. This is the case only with Money Bills and not with a Non-Money Bill. When it comes to a Non-Money Bill, the President has an element of discretion. Three is that the Council of States is not at the same pedestal as the House of the People in case of Money Bills as it is in case of Constitution Amendment Bills. Therefore, if the ordinary law concerned is a Money Bill, the Council of States has no determinative say in its enactment. Four is that while a Constitution Amendment Act that deals with Centre-State relations must be ratified by State Legislatures, there is no such process of ratification envisaged in case of ordinary laws.[21]

What these differences emphasize is not that one procedure is more burdensome as compared to the other, but that neither procedure can supplant the other. Thus, as has also been held by Justice Palekar in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, while a Constitution Amendment Act must necessarily be passed as per the procedure laid out in Article 368, an ordinary law must mandatorily be passed in compliance with Articles 107 through 111.[22] To do otherwise, would be to violate the provisions of the Constitution and also, to gloss over the material differences carved out by it. Section 18 of the Amendment Act- a provision of ordinary law- should therefore have been passed in pursuance of the power conferred under Articles 245 and 246 and in compliance with the procedure contained in Articles 107 through 111 of the Constitution. As the same has not been done, Section 18 can be said to be in violation of the provisions of the Constitution and thus, unconstitutional.[23]

However, even if one were to assume that the constitutional validity of Section 18 was upheld on the ground that an ordinary law can be enacted by means of a Constitution Amendment Act there is another hurdle that Section 18 will have to surpass.

Section 18 uses the phrase, “Parliament shall, by law,…”. Admittedly, this is not a provision in the Constitution. The Constitution can direct the Legislature to mandatorily do something. In this case though, it is the Legislature that seeks to bind itself. Therefore, the question to be answered is whether this is permissible.

Article 245 vests the legislative power in Parliament. The power of the Parliament is curtailed only by the provisions of the Constitution. Subject to the limitations imposed by the Constitution, the power of the Parliament to legislate is plenary. It can choose whether or not it wants to make a law on a particular subject matter. Over and above what is prescribed by the Constitution, no fetter can be imposed on this power.[24]

Section 18 though creates a unique situation wherein a direction to legislate has been issued by the Parliament itself. Even then, Section 18 is not a provision of the Constitution. It is a measure in addition to the limitations placed by the Constitution. Therefore, it is contrary to the mandate of Article 245 and would thereby be violative of the Constitution. Moreover, to hold otherwise would also set a dangerous precedent. It would mean that the political party which commands a majority in Parliament would create laws that bind future Parliaments and would thus abuse its majority.

Assuming that the constitutional validity of Section 18 is upheld on both the grounds discussed above then, Section 18 would be an ordinary law in a Constitution Amendment Act. This would not be beneficial to the assessees who may seek to challenge the constitutionality of Section 18 to avoid the payment of cess levied for the purposes of compensation. However, it could lead to a peculiar political situation wherein the Parliament would have the power to unilaterally repeal Section 18, an ordinary law passed by it, and to thereby do away with the need to compensate the States. As a consequence, the very promise that constituted a mainstay of the negotiations to secure the consent of the States to GST could come to be negated. From the perspective of State Governments thus, the inclusion of a promise to compensate as an ordinary law means that it is either unconstitutional or subject to the discretion of Parliament. The supposed ‘sanctity’ of the promise is absent.

[1]Goods and Services Tax (GST) Bill, explained, The Indian Express (October 19, 2016), available at http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/gst-bill-parliament-what-is-goods-services-tax-economy-explained-2950335/ (Last visited on April 1, 2017).

[2]GST: Compensation for revenue loss remains an issue with the States, Firstpost (June 10, 2014), available at http://www.firstpost.com/business/economy/gst-compensation-for-revenue-loss-remain-an-issue-with-states-2007551.html (Last visited on April 1, 2017).

[3]Draft GST law proposes compensation cess, The Business Line (November 27, 2016), available at http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/draft-gst-law-proposes-compensation-cess/article9391872.ece (Last visited on April 1, 2017).

[4]Centre to Include GST Compensation in Constitution Amendment Bill, Livemint (November 17, 2014), available at http://www.livemint.com/Politics/PqkNXG8YVOLaJVZEUirvvO/Centre-to-include-GST-compensation-in-Constitutional-Amendme.html (Last visited on November 17, 2014).

[5]Lok Sabha passes GST supplementary bills; ‘history in the making,’ says Arun Jaitley, Indian Express (March 29, 2017), available at http://indianexpress.com/article/india/gst-bill-passed-in-lok-sabha-arun-jaitley-finance-minister-4591536/ (Last visited on April 1, 2017).

[6]Section 18, Constitution (One Hundred and First) Amendment Act, 2016.

[7]Article 368(1), Constitution of India; D.D. Basu, COMMENTARY ON THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA 11262-11265 (8th edn., 2012).

[8]Article 368(2), Constitution of India.

[9]Proviso to Article 368(2), Constitution of India, 1950; D.D. Basu, supra note 2, at 8749.

[10]Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, (1973) 4 SCC 225 (Supreme Court of India), ¶ 1876.

[11]Article 245, Constitution of India.

[12]Article 246, Constitution of India.

[13]D.D. Basu, supra note 2, at 5194.

[14]Article 107(1), Constitution of India.

[15]Article 107(2), Constitution of India.

[16]Article 108(1), Constitution of India.

[17]Article 111, Constitution of India.

[18]Article 109, Constitution of India.

[19]Proviso to Article 111, Constitution of India.

[20]Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, (1973) 4 SCC 225 (Supreme Court of India), ¶ 783, 834.

[21]Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, (1973) 4 SCC 225 (Supreme Court of India), ¶ 1222, 1223.

[22]Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, (1973) 4 SCC 225 (Supreme Court of India), ¶ 1222.

[23]One of the ways in which a statute can be held to be unconstitutional is if it violates a provision of the Constitution. See D.D. Basu, supra note, at 8969. The author takes the cases of Jawaharmal v. State of Rajasthan, AIR 1966 SC 764 (Supreme Court of India), Atiabari Tea Company v. State of Assam, AIR 1961 SC 232 and Bengal Immunity Company v. State of Bihar, (1955) 2 SCR 303 as examples for when a law was declared unconstitutional for having violated provisions of the Constitution other than those dealing with Fundamental Rights and Legislative Competence.

[24]Government of Andhra Pradesh v. Hindustan Machine Tools, AIR 1973 SC 2037 (Supreme Court of India); Maharaj Umeg Singh v. State of Bombay, AIR 1955 SC 540 (Supreme Court of India).

The article says: “…………This is the case only with Money Bills and not with a Non-Money Bill. When it comes to a Non-Money Bill, the President has an element of discretion. ” First sentence is wrong and the second one is vague. Art.111 of the Constitution of India is here: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/158646/.

In the case of Money Bill, the President is denied the power of returning, but right to reject is intact. Thus, it is not the same as the Constitution Amendment Bill. For non-money Bills, the full spectrum of Presidential options is open. Further, for reasons of technical accuracy, down the same para, if it is said” Constitution Amendment Bill”, that will be complete justice. SRIRAM’s IAS, New Delhi.

https://indconlawphil.wordpress.com/2019/02/14/guest-post-a-comment-on-the-supreme-courts-verdict-in-union-of-india-v-mohit-minerals/