A mass movement led by students has ushered in a new dawn in Bangladesh. What began as a claim for reform of the quota system transformed into a national movement to oust Bangladesh’s long standing autocrat from office after 15 years. In the aftermath of Sheikh Hasina’s fall, the question on everyone’s mind has been where to go from here. An interim government has been formed under Professor Muhammad Yunus, with a cabinet of advisors including a handful of technocratic experts, two students from the movement and a selection of lawyers, NGO leaders and activists, and a representative of one of the mainstream Islamist parties, the Hefazati Islam. Key tasks ahead of this government will be to restore law and order, steer the bureaucracy and state apparatus, and prepare for electoral transition. This commentary examines some of these issues.

2. Bureaucratic Considerations

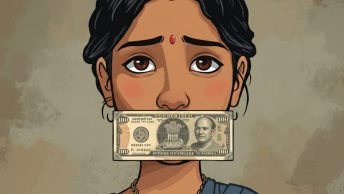

In recent years, government jobs in Bangladesh have become lucrative with pay-scale reviews, making these positions aspirational for both public and private university students, which was not the case just a few years ago. Moreover, with greater demand for such employment, different groups now compete for their stake in government service. The Liberation War veterans and their descendants were deprived of quotas between 1975 – 1996, and thus consider themselves (as endorsed by the HCD’s quota judgment) to be backward section of society (Article 29, Constitution) deserving affirmative action. By contrast, many involved in the protests viewed the inclusion of grandchildren of veterans in these quota allocations as a means for enabling further nepotism and corruption among the AL loyalists.

Bureaucratic tension and cleavages regarding service, recruitment and promotion has been a defining feature of constitutional and political contestation in Bangladesh and elsewhere in South Asia, a shared legacy of British colonial rule. Government service jobs have been central to upward social mobility and acquisition of political capital by forcing concessions from the state. It should come as no surprise if drawing room conversations of many middle and upper middle-class South Asian elites still refer (with some nostalgia) to some sort of civil service family lineage. The lack of government jobs for Bengalis in East Pakistan were a key grievance in the 1960s, that presaged the Liberation War in 1971. After independence, successive military governments continued the practice of tightly controlling recruitment. Under political parties post-1991, these services reached new heights of politicization. No cadre was immune from the AL-Bangladesh Nationalist Party (“BNP”) factionalism, which gradually spilled over among civil society, student bodies and professional quarters, including medical and legal associations. The AL-BNP/Jamaat rivalry extended its tentacles across all institutions, which the AL perfected in its longest tenure in office (2009-2024). Given the mass politicization of public institutions, it is likely that internal grievances and fragmentation exist across civil, judicial, law enforcement and military cadres. One of the key tasks of the interim Government will be, among others, to surmount these divisions and restore chain of command—a task perhaps better suited for former bureaucrats and technocrats among its advisors.

III. Failure of Institutions

There are calls now for a new Constitution from some quarters, including from some leftist groups, and some sections of the bar—perhaps the two constituencies with the least amount of legitimacy to question the Constitution. Their claim, among others, is that the current constitution is fascist, which has enabled abuse of power, exclusion of certain groups, rights violations, etc. In general terms, constitutionalism refers to restraining the exercise of state or governmental power through formal checks and balances between the branches of government (executive, judiciary and parliament). The academia, civil society and other political constituencies and citizenry are granted with constitutional rights of free expression, critique and political organization that are intended to provide informal checks and balances through vigilance and political claim-making. . Both these formal and informal processes witnessed spectacular abdication of responsibility by institutions and individuals who inhabited them.

The Supreme Court, so central to imposing constitutional restraints, gradually absolved itself of the responsibility to protect and defend the Constitution the moment judges began to be recruited and promoted based on party affiliations rather than merit. Since 1991, the bar elections also became highly partisan based on direct political party affiliation. The legal profession, including the bar and judiciary, has contributed in no small measure to the systematic amendment and interpretation of the Constitution for political gain since the Fourth Amendment in 1975 (which led to a one-party state under a presidential system). Academia too has been divided along BNP-AL lines, abdicating its responsibility of critique. The leftist groups having little to no constituency in a country of mass proletariats, have been largely riding on the coattails of the AL, invested in improving the League— providing a veneer of left-leaning policies within this largely centrist bourgeois party.

With each alternating regime after 1991, the process of fusing the state and private interests began in earnest, constrained every 5 years by the caretaker government (CTG) system. Past CTGs typically consisted of technocrats, former bureaucrats and civil society advocates affiliated with progressive organizations, NGOs and non-profits. The CTG needed neutral individuals to run it, and it became quickly apparent that increasingly there were few such people left. Political parties on the losing side of elections began to question their neutrality. The last caretaker government backed by the miliary served two years between 2007-2008. This long tenure subsequently became fodder for the AL’s political maneuvering. The AL questioned the political ambition of the civil society, which it later used as justification to curb fundamental freedoms and civic space through draconian laws like the Digital Security Act, 2018, and the Foreign Donations (Voluntary Activities) Regulation Act, 2016. The AL’s tenure also witnessed general fragmentation among the civil society over the politics around the war crimes trials and the liberation war’s historical narrative. AL’s 15-year rule in power presented 3 choices— perish, join in, or be silent. Sadly, too many were complicit in active participation or silence. Thus, when considering reforms, the interim government may consider striking a balance between expertise and objectivity in its institutional appointments, laying special emphasis on legal process.

- NGO-ization and Student Politics

Drawing in civil society and NGO actors into the current political fray may impact the informal check and balances they serve within the political system through ostensible neutrality. The already existing dysfunction in Bangladeshi civil society is palpable if one were to examine the concentration of many well-resourced NGOs within the capital city in elite spaces, and the length of time their executive directors have served in office—some going back even as far as the eighties and nineties. Thus, organizational strength and capital is often based on the cult of personality, thereby failing to pave the way for a second generation of development professionals; or even perhaps failing to stave off nepotism. Civil society dysfunction, thus, poses dangers of shrinking spaces for self-reflection, internal critique, and participation of plural voices and constituencies.

The student movement’s initial 9-point demands sought to broadly clean up party-led student politics in universities, redress the violence and injustice of the regime against the protesters, and generally address the abject moral economy of corruption and nepotism facilitated by dynastic politics. Historically, student politics has been the life blood of various sociopolitical movements the Language Movement of 1952 and the 1971 Liberation War. Bengal itself prior to 1947 had been home to various agrarian and anticolonial movements of all stripes. Many such movements owed their success to the objective conditions of exploitation that the people of this region had suffered and political organization and mobilization from which new leaders emerged, who questioned the old order.

A cluster of student coordinators successfully led the awe-inspiring movement of the present. However, no indication exists of new political organizations emerging from it (other than a brief announcement that the students were considering forming a party), and whether such organization will be able to compete with a deeply entrenched two party system. There are few success stories in the region of civil society movements reorganizing itself as a political party. The Aam Aadmi Party (“AAP”) in India is perhaps a rare example. Kejriwal split from the Anna Hazare non-aligned camp to form his own party, and yet the AAP occupies a sliver of the larger national political space.

Given that two student coordinators have been made advisors to the government with important ministerial portfolios—a move though lauded by many—also presents some potential danger of deradicalizing the student movement or potential fragmentation within the group—some possible pitfalls of the NGO-ization of politics. The upward mobility offered to these young advisors may well prompt their peers to do the same, especially as the BNP’s student wings are likely to be back on the ground in search of recruits since their party appears to be calling for relatively swift elections in which it currently has no other serious contender or alternative.

It is unclear what the agenda and tenure of the interim government may look like. However, more than one member of the interim government has stated that the government will stay in power as long as is necessary. While it is still early days and the interim government certainly needs time to organize itself, should the citizenry indefinitely rely on the benevolence of the interim government and individuals in charge of it? In just over 5 decades, Bangladesh has experimented with military governments, presidential and parliamentary systems, one party, multi-party and the caretaker system. There is demonstrable evidence in Bangladeshi politics showing authoritarian tendencies across all these political configurations. Democratic systems function better with checks and balances rather than dynasties or cult personalities. An unelected government for an indefinite term cannot be the answer to the present crisis. If the student movement is seeking to create an egalitarian society, it may not want to do so at the cost of democracy.

Additionally, it is unclear to what extent the interim government will be allowed to do its job. A new Attorney General was appointed mere hours before swearing in of the interim government. Subsequently, the students gathered in the Supreme Court to not only demand the resignation of the former Chief Justice; but also, the appointment of a candidate of their choice in his place. These actions after an interim government (with student representation) has been formed inspire little confidence. The quality of candidates is not under question, but if proper legal procedures are bypassed—especially in the absence of any compelling necessity—it may result in the usurpation of the interim government’s functions. Thus, many additional challenges may lay ahead.

Click here for Part III of the series.

Cynthia Farid is a Global Academic Fellow at the Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong.

Ed Note: This article has been edited by Sukrut Khandekar and published by Abhishek Sanjay from the Student Editorial Board.

[…] Posted byCynthia Farid […]

Spor Habeleri,Güncel Haberler, Sondakika Haberleri

Atasehir bölgesinde ev arayisiniz var ise, sizlere atasehirsatilik.com sitesini kesinlikle öneririm. Satilik Daire, Dükkan, Arsa ve Ofis imkanlari ile Atasehir bölgesinde profesyonel emlak hizmeti saglamaktadir.